LINKS WE LIKE #42

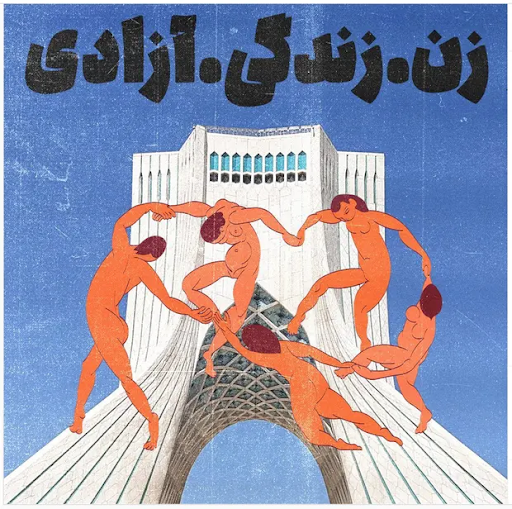

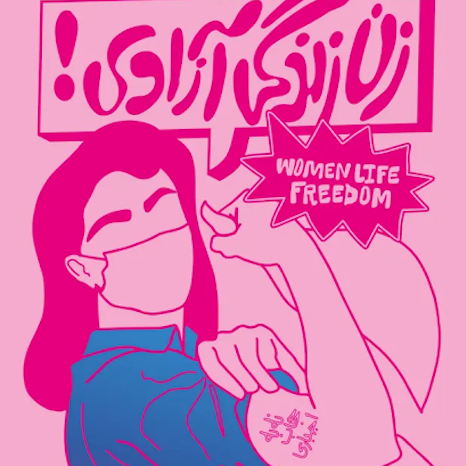

“Woman, Life, and Freedom”

Chant of Ongoing Protests in Iran

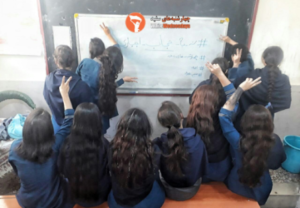

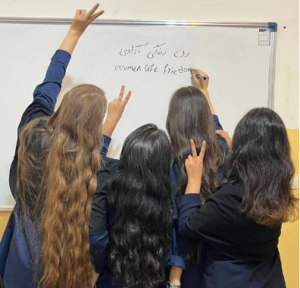

On September 13, 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini was arrested by Iran’s morality police for “improperly” wearing her hijab. Three days later, after being held captive in Vozara detention center to be “educated”, she went into a coma with a level-three concussion and later died in police custody. Authorities denied killing Mahsa Amini and blamed her death on health complications, however, her family alleges that she was badly beaten and ultimately killed. Her death sparked protests against Iran’s authoritarian government and legal codes, with thousands of people in more than 155 cities chanting “Women, Life, and Freedom” as a protest against the regime. Despite severe repression and the killing of many protestors (it is estimated that at least 524 have been killed) many women, especially younger women, have taken Mahsa Amini’s death as the spark to resist the oppressive laws that limit their right to liberty and self-expression. There have been hundreds of videos showing Iranian girls cutting off their hair and burning their hijabs, and well-known Iranian women have appeared on social media without their hijabs. Their fight has been so intense and persistent that they have received international attention, and millions around the world have seen the unfiltered version through the social media posts shared by protesters.

What is the Role of Social Media in the Protests?

Iran has a large youth population (about 60% of the total population) which has taken the lead in the movement against Iran’s repressive laws. They have taken to social media, using apps such as TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter to document and share the reality of what they face. Through these channels, they have posted poems, songs, signs, and images with a strongly defiant message against the government which have helped to create awareness and empathy for their cause. One example of this impact is that Mahsa Amini’s hashtag (in Persian) became the first in the history of Twitter to record more than 250 million tweets.

Which leads to the question, why have these communication channels gained so much traction? There are a few key reasons. The first is that news outlets in Iran are strongly influenced by the government and therefore tend to report a biased version of events in favor of the ruling party and law enforcement. In the case of the protests, official reports have only counted a fraction of what civil society organizations have estimated to be the total number of protesters killed. Likewise, when young protestor Nika Shakarami was found dead, the national broadcast network attributed her death to an accident, alleging that she fell from a building. However, evidence from videos of different protestors has surfaced showing she was taken by the police. Death certificates from the BBC (verified by CNN) have also emerged stating she died from “multiple injuries caused by blows with a hard object.” This is one example of how social media has played a vital role in dismantling false narratives and shedding light on what is truly happening on the ground. Social media has not only been key in spreading the word on the killing of Mahsa Amini, but also exposing police brutality in response to the protests. All in all, social media has been one of the only ways the world has been given unrestricted and unbiased accounts of what is happening.

Another reason is that social media channels have served as a tool for organizing protests and coordinating resistance efforts. For example, the Telegram app has spread widely throughout the country and gained 45 million users, which account for half the population of Iran. Protestors have been using this app, as well as Instagram and Twitter, to coordinate efforts and agree on meeting points, provide assistance to protestors who have been detained, and support each other throughout the protests. However, despite all these channels, communication can still be a problem due to government-initiated internet shutdowns. To address this issue, hackers have developed tools such as VPNs and Tor servers to bypass internet blocks and allow protestors to continue communicating. This strategy has been used since the uprising in 2019, however, this time they have been much more effective and been able to keep protesters’ lines of communication open. There is no doubt that these efforts have been crucial in allowing Iranian citizens to remain connected with each other, communicate with loved ones, and warn of problems that may arise during the protests.

To learn more about these efforts, join us in this edition of Links We Like, as we use curated resources from around the Internet to explore the role social media has played during the protests, and the ways in which Iranian protesters have expressed their discontent with their country’s repressive regime and restrictive laws.

Although Iran has a history of restricting citizens’ access to social media platforms, particularly Facebook, Twitter, and Telegram, two apps, Clubhouse and Instagram, have not been targeted as heavily, which has raised questions as to why the government chooses to allow their usage. This article argues that this is attributed to Instagram’s role as a popular venue for advertising, and boosting small businesses in Iran, especially during the COVID-19 crisis. The app has also played a role in generating revenue for the government– through tax payments for accounts with over a million followers– as well as providing a platform for cyber propaganda and intelligence gathering by the authorities. However, despite being less frequently blocked than other apps, Instagram has faced more outages during the current mass protests, and reports of unexplained profile disabling of protestors have also been reported.

Holly Dagres, an Iranian-American and author of this Foreign Policy article, is also a fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Program and the author of the “Iranians on #SocialMedia” report. Published in 2022, the document brings together chapters on apps and social media numbers; commercial, cultural and entertainment uses; sociopolitical use; how the government is fighting back, Internet shutdowns and sanctions; and reflections on whether the internet can “liberate” Iran.

In this piece, researcher Parichehr Kazemi comments on the role of digital visual content in exposing events to the external public and their symbolic functions as memorial recordings, as well as its important role for the evolution of activism itself. Based on her own research on Iran’s “My Stealthy Freedom” movement since 2014, images and videos of the Iranian movement build on over a decade of prior digital visual activism. Women and girls have taken photos and videos of themselves partaking in publicly banned activities in protest of Iran’s gender discriminatory policies. The bridges between past and present are exemplified in a series of photos that show women and girls in similar poses.

Twitter has played an important role in giving Iranians a way to document and share information about the ongoing protests, which have been met with increasing violence from Iranian forces. The platform, recently purchased by Elon Musk, has been used as a way to broadcast protests and human rights abuses around the world for more than a decade. Still, with the recent takeover, experts and others monitoring the protests are concerned that it may damage a key platform for protest and activism at a time when Internet freedoms are being curtailed. Although Twitter is not the most popular social network in Iran, it is still used to share breaking news and real-time updates on events, and to hold the government accountable. The article argues that Musk’s recent changes to the platform, such as “gutting the Human Rights team”, could have real consequences for Iranian’s safe use of the platform as the government has been known to monitor protesters’ social media, which has led to arrests.

In 2022, after the killing of Mahsa Amini, a new wave of protests erupted in Iran. Although religion and the hijab are part of the narrative, Saeed Bagheri goes beyond these facets, exploring the core of the conflict, which includes the dominance of a dictatorial regime, violations of human rights, and suppression of the opposition. Bagheri examines shocking statistics about Iran’s judicial system and law enforcement: “More than 1,000 people have been charged with a variety of offenses in the Tehran province for involvement in the protests. Mohammad Ghobadlou, 22, has reportedly been sentenced to death for hitting and killing a police officer with his car during the protests, but this has not been confirmed.”

Social media has been an important tool for Iranian women and girls to organize and share information during the recent protests for women’s rights. Platforms such as Telegram and Instagram have been widely used to spread news and images of the protests, as well as to coordinate and mobilize demonstrators. However, as this article points out, the government of Iran has blocked accounts and monitors these platforms to limit the spread of information and to track down and arrest protesters, while tech companies have been slow to respond to the issue. This has left families such as Nika Shakharami’s, who’s Instagram account was mysteriously deactivated shortly before her disappearance, longing for answers and for justice.

In the face of Internet blockades imposed by the country’s government, many Iranian women artists in the diaspora have kept the message of protesters alive around the world. Through the use of symbols of protest and freedom, they have shown their support for women’s rights. Some of the examples are Jalz, Touraj Saberivand, Sahar Ghorishi, Ghazal Foroutan, Atieh Sohrabi and Mahdieh Farhadkiaei.

Most of the artistic expressions of the current protests take place on social media, with the creators frequently remaining anonymous to protect their safety. These are examples of artistic expressions of 2019 on Twitter.

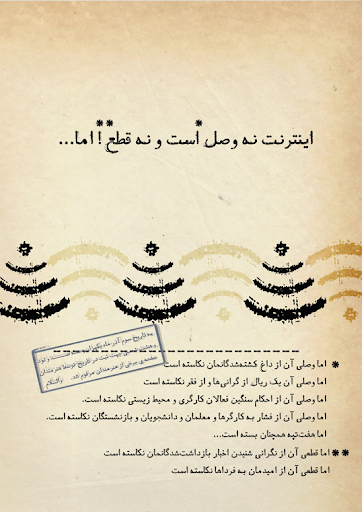

Translation:

“[The stamp reads] On this date, 3rd of Azar 1397, this note was penned for historical documentation by artists from the Some Artists page, Va al-Salam.

The internet is neither connected* nor disconnected**! But . .

* But its being connected has not reduced the grief of ours killed.

But its being connected has not reduced high prices and poverty.

But its being connected has not reduced the heavy prison sentences for labor and environmental activists.

But its being connected has not reduced the pressures over laborers, teachers, college students, and retirees.

But Haft Tappeh Factory is still closed down . . .

** But its being disconnected has not reduced worries over news of arrests.

But its being disconnected has not reduced our hope for tomorrow.”

“Barayeh” has become the anthem of the ongoing mobilizations. It is a song written by Shervin Hajipour and released on the internet on September 28, 2022. The lyrics sum up the aspirations, demands, and suffering of the Iranian people.

“For the feeling of peace

For the sunrise after long dark nights

For the stress and insomnia pills

For man, motherland, prosperity

For the girl who wished she was born a boy

For woman, life, freedom.”

Further Afield

Background on the Current Protests and Political Landscape

Women, Life & Freedom Movement

- Women, Life, Freedom: In a Moving Short Film, Roxy Rezvany Zooms In on the Protests in Iran

- Mapping Iran’s unrest: how Mahsa Amini’s death led to nationwide protests

- Meet Iran’s Gen Z: the Driving Force Behind the Protests

- Women, Life, Freedom

- “Woman, life, freedom!” an activist continues her fight for women’s rights

- Why is Iran’s TikTok generation demanding ‘Women, Life, Freedom’? – BBC News

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)