Current economic models and budget processes often overlook gender dynamics, leading to fiscal policies that unintentionally reinforce inequality. In countries like Pakistan, where gender disparities are deeply entrenched, this can exacerbate unpaid care burdens or stall progress on women’s rights. Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) addresses these gaps by ensuring that expenditures and revenues consider the diverse needs of all citizens (UN Women, 2023).

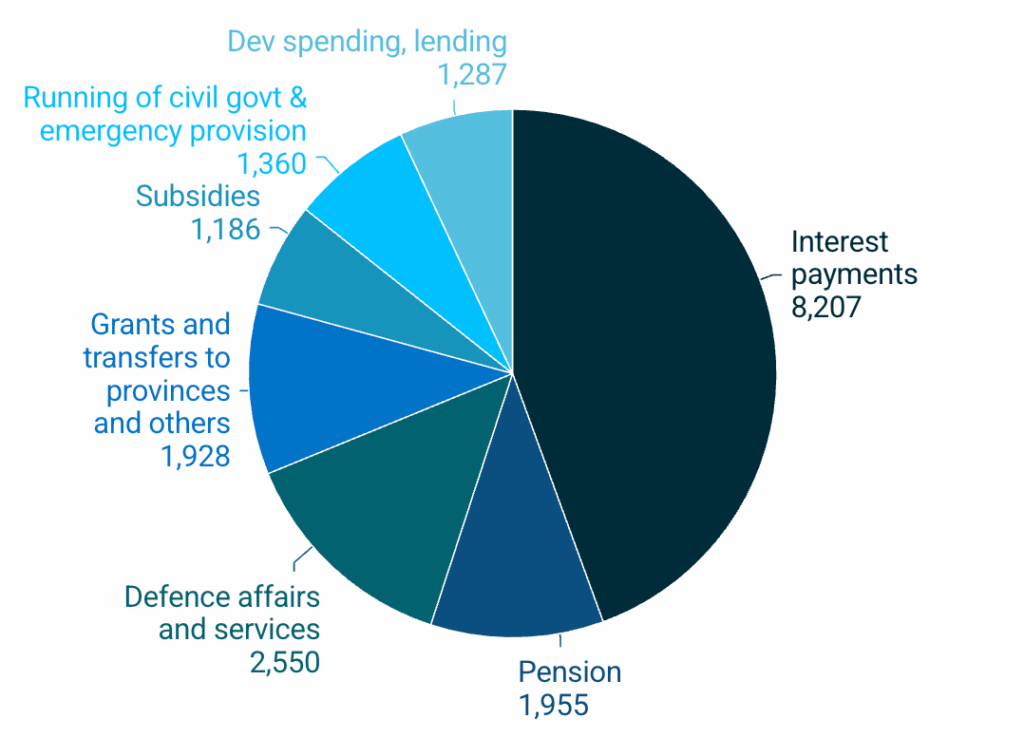

Like many countries, Pakistan publishes a federal budget each fiscal year, and its 2025–26 budget drew widespread criticism for its priorities. Approximately Rs 8,207 billion (nearly half of total government spending) was allocated specifically for debt servicing (Sadozai, 2025). At the same time, defence spending jumped by 20.2%, driven partly by heightened tensions following a recent conflict with India (Clary, 2025). With such a heavy emphasis on debt repayment and defense, funding for human development sectors like health, education, and social protection – critical areas for women and children – faced significant cuts. Women are often the most vulnerable to this kind of austerity, since they often rely more on public services and social safety nets. Given these patterns, it is essential to evaluate Pakistan’s budget through a gender lens. This blog post begins by outlining the country’s gender context and key challenges, then examines the 2025–26 budget in relation to these issues, and concludes with recommendations to guide more equitable and inclusive future budgets.

Pakistan’s Gender Equality Context

Pakistan is a signatory of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but like many signatory countries, it has achieved very few targets. Equal Measures 2030 – which monitors global progress on gender-related SDGs – projects that at Pakistan’s current pace, there will be virtually no progress toward a more gender-equal society by 2030. In fact, Pakistan ranks 123rd in Equal Measures’ SDG Gender Index, reflecting “very poor” overall performance and lack of improvement since 2015 (Equal Measures, 2030).

A closer look at this data shows that Pakistan scores relatively well on a few gender policy indicators: Indicator 5.5 (proportion of ministerial or senior government positions held by women) shows improvement, and Indicator 8.4 (laws mandating women’s equality in parenthood and caregiving) is robust on paper. Additionally, Indicator 5.2 (proportion of women who report having supportive friends or relatives in times of trouble) suggests strong social networks for women. These findings imply that Pakistan has certain legal frameworks and community support systems in place.

However, Pakistan’s worst-performing indicators carry deeper socio-economic implications that directly affect women’s daily lives. For example, Indicator 4.1 (the proportion of girls enrolled in pre-primary education) is extremely low. Even more telling are indicators seemingly unrelated to gender, at least at first glance: Indicator 17.2 (central government debt as a % of GDP) and Indicator 11.4 (quality of trade and transport infrastructure) – and in Pakistan’s case, public debt or infrastructure quality matter for gender equality.

High public debt often forces governments into fiscal tightening and austerity. When a large portion of the budget is earmarked for interest payments, there is less money available for essential public services. If schools and clinics receive less funding, girls are often the group pulled out of school first. Additionally, women may face reductions in maternal healthcare. In extreme cases, economic hardship in vulnerable communities can lead to early marriages for girls as parents try to cut household expenses and secure their futures (Musindarwezo & Jones, 2019). As such, heavy debt servicing can result in human rights setbacks for women.

There is another side-effect: pressure to raise revenues quickly, often through indirect taxes, such as general sales tax (GST/VAT). Although often considered “neutral,” these taxes disproportionately affect low-income households, particularly women, who tend to spend a larger share of their income on VAT-taxed essentials like food, healthcare products, and school supplies. Subsequently, women shoulder a heavier tax burden relative to their income (Joshi, Kangave & van den Boogaard, 2020). In contrast, corporations benefit from tax relief, shielding wealthier groups while the average woman pays more for everyday essentials. This dynamic widens the gender gap in economic security, as women’s purchasing power and savings diminish more rapidly than men’s.

While infrastructure (Indicator 11.4) may seem gender-neutral, inadequate transportation and trade systems have clear gendered consequences. Poor roads, unreliable public transport, and unsafe travel routes restrict women’s mobility and access to jobs, markets, schools, and healthcare. In many Pakistani communities, women are primarily responsible for unpaid tasks such as collecting water, gathering fuel, or escorting children to school—duties made significantly more difficult by infrastructure gaps. When clean water is unavailable nearby, it is typically women who walk long distances to fetch it, losing valuable time and facing risks of harassment or violence along the way (Tallman et al., 2023).

Urban women reliant on public transport often face safety risks too due to poorly lit streets, overcrowded buses, and lack of last-mile connectivity. One study on mobility found that women consider factors such as the adequate street lighting and safe travel speeds when deciding whether to walk in an area. When such features are lacking, women curtail their movement (Clifton & Dill, 2005). And it’s not just fear, many women in Pakistan have firsthand experiences of catcalls, stalking, amongst other types of gender-based violence in public spaces (Low, Taplin, & Lamb, 2005). Furthermore, few transport options cater to “trip chaining,” where a woman might drop a child at school on the way to work, then stop for groceries on the way home (Frank, 2023). The net effect is that weak infrastructure confines women to a smaller radius of opportunity, reinforcing gender roles and limiting their economic and social participation.

Overview of the 2025–26 Federal Budget

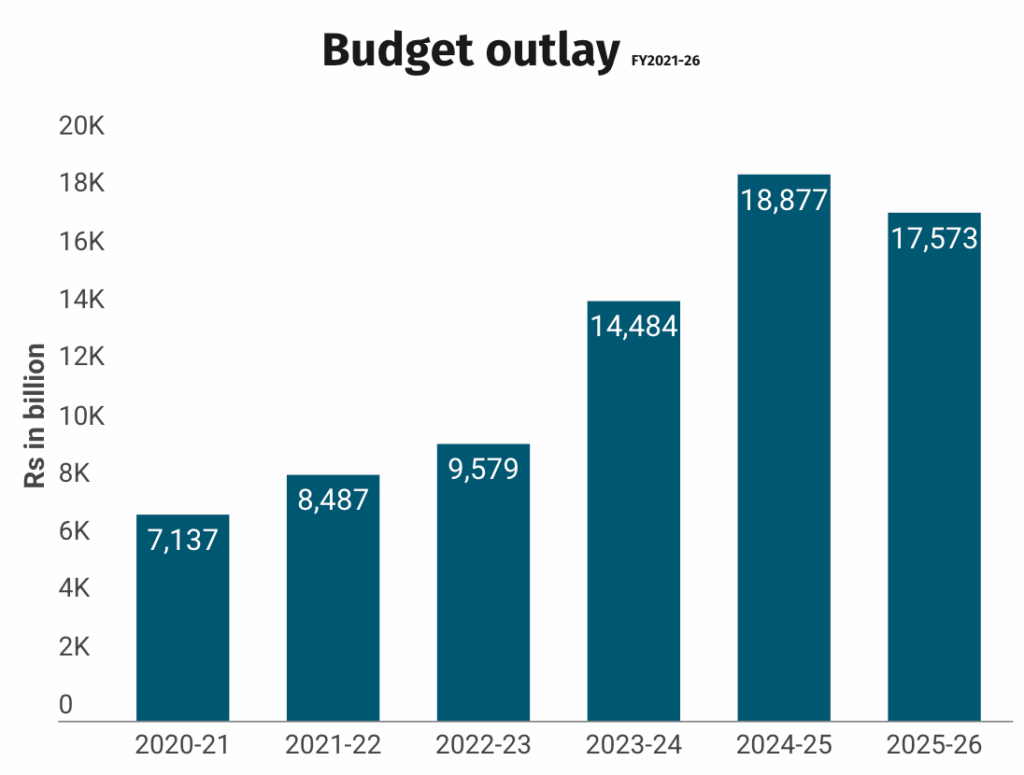

Pakistan entered fiscal year 2025–26 in a precarious economic state, grappling with massive debt, post-crisis recovery from a phase of instability, and security pressures. The federal budget announced for FY 2025–26 has a total outlay of Rs 17.573 trillion, which is actually a 6.9% decrease from the previous year’s budget.

As noted, interest payments on public debt currently consume nearly half of the total budget. Although repayments are about 16% lower than last year, debt servicing remains the largest single expenditure of the federal government. This severely limits the fiscal space for development and social programs. The second-largest outlay is defence, budgeted at Rs 2,550 billion.

Funding for ministries and programs focused on health, education, and social protection saw only modest increases or even real-term declines (accounted for inflation). The budget speech did highlight certain initiatives – for example, a 10% pay raise for federal government employees and a 7% pension increase for retirees (Sadozai, 2025). These measures provide some relief, however, broader social spending did not get a dramatic boost. In fact, 118 development projects were cut or scaled down, and spending in these sectors remains far below adequate levels. Pakistan’s expenditure on education is around 1.7% of GDP and on health around 1% of GDP, translating to crowded classrooms, missing teachers and doctors, and long wait times for basic health services. While these challenges affect the entire population, they often have an outsized impact on women and girls.

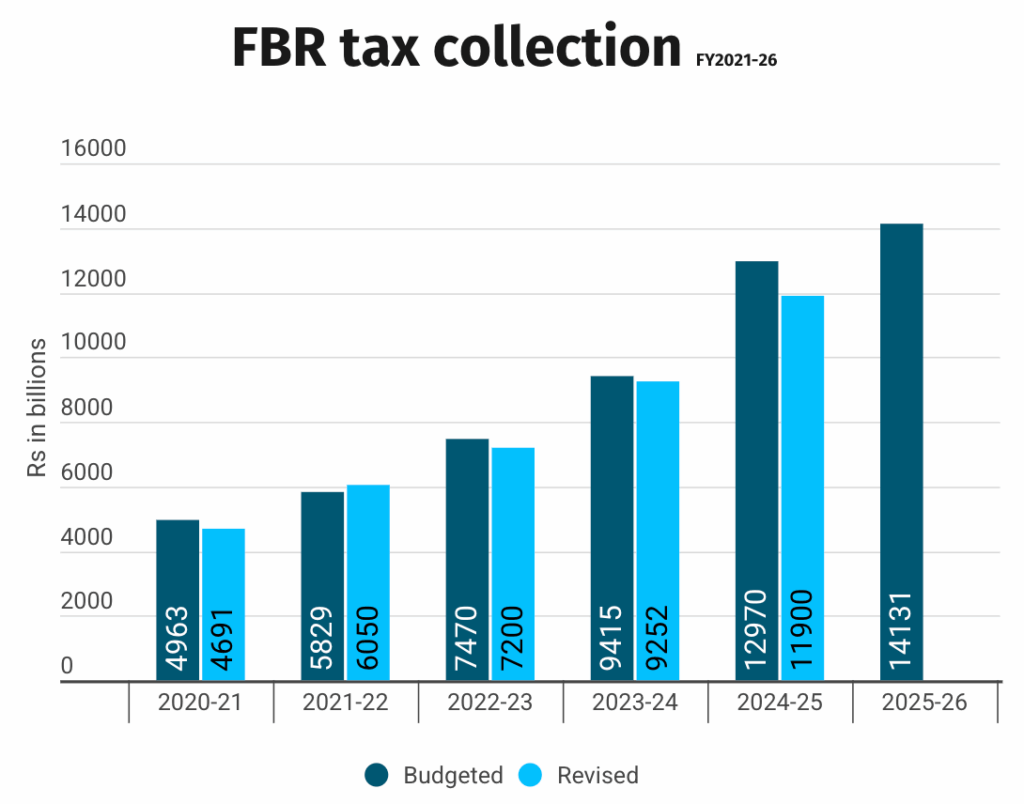

On the revenue side, the budget targets a tax-to-GDP ratio of 14%, with an ambitious collection goal of Rs 14.13 trillion (Sadozai, 2025). To reach this, the government introduced several new measures—many of which are indirect taxes. An 18% GST now applies to previously exempt goods such as imported solar panels, petrol, diesel, and hybrid vehicles. Additionally, online businesses and digital marketplaces will be brought under the tax net. On the direct tax front, there is modest relief for lower-salaried individuals to help offset inflation, and withholding taxes on property transactions have been reduced to stimulate real estate activity (Sadozai, 2025). However, this approach places a heavier burden on average consumers, particularly women managing household expenses, while wealthier groups benefit from more favorable tax provisions.

Regarding social protection, the flagship Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), which provides cash transfers to the poorest households, continues to be supported. Over 11 million children are now aided through education stipends) and 1.5 million mothers receive financial assistance, alongside programs like financial literacy training for 250,000 people (Sadozai, 2025).

Gender Analysis: Linking Budget Choices to Women’s Lived Experiences

Having mapped Pakistan’s gender equality challenges and the broad strokes of the 2025–26 budget, we can now examine how these budget choices intersect with gender. The budget’s enormous debt servicing allocation represents resources not available for social investments that benefit women. As noted earlier, debt servicing comes at the expense of social welfare, thus, in the current budget many programs that economically empower and support women are missing or under-funded. For example, Pakistan has laws and policies for women’s protection and empowerment. However, without sufficient budgetary allocations, these laws and policies remain “paper promises” (UN Women, 2023). The budget therefore reinforces structural inequalities instead of remedying them. For women, austerity embedded in the budget translates into daily struggles including fewer nurses and health workers available at clinics, fewer girls’ school facilities, and reduced support for programs aimed at economic empowerment. Women constitute a significant portion of teachers, healthcare workers, and clerical staff, so budget cuts in these areas not only threaten women’s jobs, but also reduce services that employ and serve women (World Bank, 2019). In short, the budget’s response to the debt crisis may be shifting the burden of debt to the women in Pakistan.

The budget’s shift toward indirect taxation raises important concerns. Although the government offered modest income tax relief for middle-income earners, the expansion of sales and consumption taxes is more consequential. These taxes function as flat levies on essential goods, disproportionately impacting women—particularly in low-income households—who are typically responsible for managing food, fuel, and household expenses. For instance, a higher GST on fuel directly increases transport and electricity costs, forcing families to divert money from groceries to cover rising commute and utility bills.

Conversely, the inclusion of corporate tax breaks in the budget signals a prioritization of large businesses over the well-being of ordinary citizens. Micro-businesses, many of which are run by women, receive no comparable support. Moreover, the budget lacks any tax measures that address gender-specific needs. There is no mention of reducing taxes on women’s health and hygiene products, such as eliminating the so-called “tampon tax” (Büttner, Hechtner, & Madzharova, 2025), nor of offering tax credits to employers who provide childcare services. From a gender perspective, the current tax policy risks deepening economic inequality. Women’s effective tax rate, or the share of income paid in taxes, is likely to increase (Investopedia, n.d.), even as access to essential public services declines.

Pakistan’s budget documents now include some gender tagging of development expenditures, which is a positive step in principle. The government’s Gender Budget Statement 2025–26 claims that 6.9% of the PSDP (Rs 291 billion) is tagged as “gender-sensitive” spending (Government of Pakistan, 2025). Gender-responsive budgeting efforts have classified over 5,000 federal cost centers under categories like education, health, governance, economic opportunity, safety, and political participation from a gender perspective. This demonstrates a commitment to integrating gender considerations across various sectors. However, without substantial funds and concrete action, such tagging can become a bureaucratic exercise rather than real change (Tariq, 2025).

One contrasting bright spot in the FY 2025–26 budget is the significant increase in allocations for “Health & Well-Being” under the gender-related categories, reportedly rising from Rs 638 million last year to Rs 15,774 million this year (Government of Pakistan, 2025). This may indicate new investments in healthcare access which would directly benefit women. Similarly, increases under categories like “Safety & Security” and “Employment & Economic Opportunity” suggest some recognition of women’s needs for safe public spaces and jobs. However, these broad categories are not the same as dedicated, women-specific programs. In fact, a dedicated fund for gender equity initiatives was cut by nearly half – from Rs 290 million in FY 2024–25 to only Rs 155 million in FY 2025–26 (Government of Pakistan, 2025). It raises the question of whether gender responsiveness is just being mainstreamed as a checkbox activity, without political will to finance real change.

The reduction in the federal PSDP limits the government’s ability to advance nationwide gender-focused initiatives. Projects such as establishing women’s shelters or launching a national maternal health program would now require provincial buy-in and co-funding, which may not be guaranteed. Without strong federal leadership, regional disparities risk deepening, particularly for women in more conservative or resource-constrained provinces. Additionally, the budget introduces no new flagship programs or significant interventions to support women’s economic empowerment, education, or safety. A truly gender-responsive budget might include a national action plan with dedicated funding to combat gender-based violence, initiatives to promote girls’ education in the poorest districts, or subsidies for childcare to support working mothers—yet no such measures were announced.

In light of this analysis, we return to the core question: Is Pakistan practicing genuine gender-responsive budgeting in FY 2025–26? The evidence suggests that while Pakistan has started talking about GRB and has taken some preliminary steps, the budget remains far from truly gender-responsive. The government did introduce a “Gender Budget Statement” and a tagging process, indicating awareness that budgets need to account for gender impacts. There are also some encouraging allocations such as boosts in health and security programs that could benefit women, continued funding for BISP cash transfers to women and so on. These reflect a degree of policy intent to integrate gender considerations. Pakistani authorities have also involved parliamentary committees on gender mainstreaming and human rights in reviewing the budget, which is a positive move towards inclusive dialogue (Sadozai, 2025). However, a truly gender-responsive budget goes beyond intent and labels – it requires significant resource shifts and concrete interventions that directly address gender inequalities.

Recommendations for a Gender-Responsive Future

Pakistan is still at an early stage of implementing gender-responsive budgeting but has the capacity to improve significantly in future budget cycles. To do so, several concrete steps can be taken. First, the government should ensure that gender equality policies are supported by dedicated and sufficient budgetary resources (Cuvillier, 2025). Key public sectors (education, health) must be treated as strategic investments rather than expendable costs.

Tax policies should be restructured to reduce the burden on low-income populations, who are disproportionately women, by shifting away from consumption-based taxes and toward those based on ability to pay. Taxes on essential goods—such as food staples and women’s hygiene products—should be reduced or eliminated. In addition, tax policy can serve as a tool to promote gender equality. This could include offering tax credits to companies that hire and train women in non-traditional roles or provide childcare for working mothers (Kronfol et al., 2019), as well as to financial institutions that expand women’s access to credit.

More development funds should be allocated to projects that reduce women’s unpaid care burden and improve their safety and mobility. Examples include building water supply systems in rural areas, enhancing public transportation and street lighting in urban centers, and constructing women-friendly public spaces and facilities. Quality infrastructure can significantly increase women’s participation in both economic and public life.

To institutionalize gender-responsive budgeting, Gender Budget Cells should be established within all ministries (UNESCAP, 2015). These units would review departmental proposals to ensure they address gender disparities in their respective sectors, such as agriculture, transport, or information technology. In parallel, the government should update key surveys—such as the National Time Use Survey (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2007)—to better quantify women’s unpaid care work and gather gender-disaggregated data on employment, income, and access to services. This data should feed into an annual, publicly accessible gender budget audit to assess how funds were allocated and what outcomes were achieved for women. Since global indices often overlook incremental progress, Pakistan must proactively track its internal advancements rather than relying solely on international rankings to spotlight the need for reform.

By implementing these measures, Pakistan can shift from a reactive to a proactive budgeting approach—where every decision is informed by its impact on all citizens. A gender-responsive budget is not a separate budget for women; it is a better budget for everyone. Advancing gender equality and women’s security will foster stronger economic growth, healthier families, and a more resilient society.

Alignment with DPA’s GRB Training in Pakistan

While Pakistan’s gender-responsive budgeting efforts remain in the early stages, encouraging signs of progress are emerging. The federal government’s introduction of a Gender Budget Statement and initial budget tagging efforts suggest a growing awareness of the need to integrate gender considerations into fiscal policymaking. These developments also reflect promising alignment with the capacity-building work led by DPA and UN Women-Pakistan in late 2024 for government stakeholders in Karachi. In particular, several overlaps between DPA’s “Gender Data Training for Inclusive and Responsive Planning and Budgeting in Pakistan” and the government’s actions to date stand out:

- Introduction of gender budget tagging, with over 5,000 federal cost centers classified by gender-related domains, aligns with DPA’s training, which equipped participants with tools to integrate gender sensitivity into financial planning.

- Inclusion of a Gender Budget Statement in the 2025–26 federal budget, echoing DPA’s emphasis on mainstreaming gender data in fiscal planning.

- Institutional engagement from parliamentary committees on gender mainstreaming and human rights, following DPA’s training sessions with policy stakeholders.

- Continued investment in social protection programs like the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), which aligns with DPA’s call to use gender data to protect vulnerable groups.

These overlaps represent important early steps toward institutionalizing gender-responsive budgeting in Pakistan. With sustained political will, not only to adopt but also to adequately fund and implement GRB measures, Pakistan has the potential to move from foundational progress to meaningful, systemic change.

Learn more about Data-Pop Alliance’s work on Gender-Responsive Budgeting in Pakistan, including a 2024 training led in partnership with UN Women Pakistan:

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)