Emmanuel Letouzé is the director and co-founder of Data-Pop Alliance on Big Data and development, jointly created by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI), the MIT Media Lab and the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). He is a Visiting Scholar at MIT Media Lab, a Fellow at HHI and a Senior Research Associate at ODI, as well as a PhD candidate (ABD) at UC Berkeley, writing his dissertation on Big Data and demographic research.

Emmanuel is the author of UN Global Pulse's White Paper "Big Data for Development" (2012), the lead author of the 2013 and 2014 OECD Fragile States reports and a regular contributor on Big Data and development.

He previously worked for UNDP in New York (2006-09) and in Hanoi for the French Ministry of Finance as a technical assistant in public finance and official statistics (2000-04). He holds a BA in Political Science and an MA in Economic Demography from Sciences Po Paris, and an MA in International Affairs from Columbia University, where he was a Fulbright fellow.

He is also a political cartoonist for various publications and media outlet including Medium and Rue89 in France, and a member of The Cartoon Movement.

Here is my interview with him:

Emmanuel Letouzé is the director and co-founder of Data-Pop Alliance on Big Data and development, jointly created by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI), the MIT Media Lab and the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). He is a Visiting Scholar at MIT Media Lab, a Fellow at HHI and a Senior Research Associate at ODI, as well as a PhD candidate (ABD) at UC Berkeley, writing his dissertation on Big Data and demographic research.

Emmanuel is the author of UN Global Pulse's White Paper "Big Data for Development" (2012), the lead author of the 2013 and 2014 OECD Fragile States reports and a regular contributor on Big Data and development.

He previously worked for UNDP in New York (2006-09) and in Hanoi for the French Ministry of Finance as a technical assistant in public finance and official statistics (2000-04). He holds a BA in Political Science and an MA in Economic Demography from Sciences Po Paris, and an MA in International Affairs from Columbia University, where he was a Fulbright fellow.

He is also a political cartoonist for various publications and media outlet including Medium and Rue89 in France, and a member of The Cartoon Movement.

Here is my interview with him:

Part 1: Big Data and Human Rights – A Complex Affair

Anmol Rajpurohit: Q1. What inspired you to launch Data-Pop Alliance? How did the team come together?

I've had the idea of creating ‘something’ like Data-Pop Alliance since about late 2012, after I left Global Pulse where I worked and wrote the White Paper “Big Data and Development” in 2010-11. That paper was my 1st foray into what was then a tiny field, and it opened doors. I was back in UC Berkeley working on my PhD in 2012-13, and was increasingly involved in the field as it started growing, talking at a few conferences, writing a few articles—and I wanted to build something lasting with a bit of a different feel and focus compared to what existed (Global Pulse, DataKind, for instance).

I wanted to create something more academic with a greater emphasis on capacity building, on politics, and work with partners in developing countries, which I had done in Vietnam for 4 years before moving to NYC in 2004. I attended many Hackathons and ‘data dives’ during those months but I didn’t think the ‘techno-scientific’ approach and the ‘data-for-good’ narrative they embodied would make much of a difference. I thought it overlooked many aspects of the problems the world faces, as I am sure we will discuss below. That was a key factor in my thought process.

Another important factor actually was meeting and talking to Kenn Cukier, the Data Editor of The Economist, and Eva Ho, who has been involved in data science for many years, at a conference in Los Angeles in the fall of 2013, who told me to go for it. That really unlocked the process in my head because it gave me the final impulse I needed to really try hard.

I've had the idea of creating ‘something’ like Data-Pop Alliance since about late 2012, after I left Global Pulse where I worked and wrote the White Paper “Big Data and Development” in 2010-11. That paper was my 1st foray into what was then a tiny field, and it opened doors. I was back in UC Berkeley working on my PhD in 2012-13, and was increasingly involved in the field as it started growing, talking at a few conferences, writing a few articles—and I wanted to build something lasting with a bit of a different feel and focus compared to what existed (Global Pulse, DataKind, for instance).

I wanted to create something more academic with a greater emphasis on capacity building, on politics, and work with partners in developing countries, which I had done in Vietnam for 4 years before moving to NYC in 2004. I attended many Hackathons and ‘data dives’ during those months but I didn’t think the ‘techno-scientific’ approach and the ‘data-for-good’ narrative they embodied would make much of a difference. I thought it overlooked many aspects of the problems the world faces, as I am sure we will discuss below. That was a key factor in my thought process.

Another important factor actually was meeting and talking to Kenn Cukier, the Data Editor of The Economist, and Eva Ho, who has been involved in data science for many years, at a conference in Los Angeles in the fall of 2013, who told me to go for it. That really unlocked the process in my head because it gave me the final impulse I needed to really try hard.

Then the project and team grew gradually. I had previously met Patrick Vinck from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative at a conference in DC, whose work I admired, and then at various events; we had several things in common–he is from Belgium, he did some cartooning in his youth for instance, which is one of my other activities, his spouse and collaborator is originally from Vietnam, etc. I floated the idea with him in the summer of 2013. He was on board right away, even as we didn’t know each other very well, and as the exact contours of the ‘something’ weren’t very clear.

The next person I talked to was Sandy Pentland, at MIT, who had been in touch a few times by email since 2011; after a few emails about the idea I asked him one day at MIT Media Lab whether he’d agree to be involved in some capacity; I was pretty nervous about it because Sandy is an important figure in the field, and he just said “sure”. I don’t really know why he agreed, but having Sandy on board was instrumental; with him we were credible. Having the institutional buy-in, the support of HHI–which their Executive Director Enzo Bolletino confirmed early on—was also key.

Then I talked to Emma Samman and Claire Melamed at ODI, whom I had known a bit for a couple of years and with whom I had several colleagues and friends in common at the UN, including Paul Ladd, who played an important role too. We wanted to build a multidisciplinary and multi-partner coalition from the beginning. Emma asked ODI’s Executive Director Kevin Watkins about it and called me 10 minutes later to say “We’re in”. We held a first informal meeting with a few key people in the space in January 2014—like Bill Hoffman from the World Economic Forum USA, Nicolas de Cordes from Orange, and it really started from there. So it seemed relatively easy to get key people excited about and by the idea, but that was built on years of connections, and the implementation was and has been of course much harder!

The first question was the name. It’s Paul Ladd, who is a close friend of mine, who found the name ‘Data-Pop’ after agonizing naming sessions—we wanted something that had data, that talked about people, about an explosion, that was a bit fun. Later we realized that there was another Data Pop, an advertising company in LA, who asked us to change the name, and we settled for Data-Pop Alliance, which I think conveys better what we are about—a coalition. The other challenging obstacle was getting other people interested and involved—advisers, partners etc.—to solidify the whole project. That took a bit of time and legwork too. I traveled a lot. In general the response was very positive. Only one institution said they were not interested in even discussing potential collaboration—oddly enough my own alma mater in France, Sciences Po. They said they didn’t see the need.

Then the project and team grew gradually. I had previously met Patrick Vinck from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative at a conference in DC, whose work I admired, and then at various events; we had several things in common–he is from Belgium, he did some cartooning in his youth for instance, which is one of my other activities, his spouse and collaborator is originally from Vietnam, etc. I floated the idea with him in the summer of 2013. He was on board right away, even as we didn’t know each other very well, and as the exact contours of the ‘something’ weren’t very clear.

The next person I talked to was Sandy Pentland, at MIT, who had been in touch a few times by email since 2011; after a few emails about the idea I asked him one day at MIT Media Lab whether he’d agree to be involved in some capacity; I was pretty nervous about it because Sandy is an important figure in the field, and he just said “sure”. I don’t really know why he agreed, but having Sandy on board was instrumental; with him we were credible. Having the institutional buy-in, the support of HHI–which their Executive Director Enzo Bolletino confirmed early on—was also key.

Then I talked to Emma Samman and Claire Melamed at ODI, whom I had known a bit for a couple of years and with whom I had several colleagues and friends in common at the UN, including Paul Ladd, who played an important role too. We wanted to build a multidisciplinary and multi-partner coalition from the beginning. Emma asked ODI’s Executive Director Kevin Watkins about it and called me 10 minutes later to say “We’re in”. We held a first informal meeting with a few key people in the space in January 2014—like Bill Hoffman from the World Economic Forum USA, Nicolas de Cordes from Orange, and it really started from there. So it seemed relatively easy to get key people excited about and by the idea, but that was built on years of connections, and the implementation was and has been of course much harder!

The first question was the name. It’s Paul Ladd, who is a close friend of mine, who found the name ‘Data-Pop’ after agonizing naming sessions—we wanted something that had data, that talked about people, about an explosion, that was a bit fun. Later we realized that there was another Data Pop, an advertising company in LA, who asked us to change the name, and we settled for Data-Pop Alliance, which I think conveys better what we are about—a coalition. The other challenging obstacle was getting other people interested and involved—advisers, partners etc.—to solidify the whole project. That took a bit of time and legwork too. I traveled a lot. In general the response was very positive. Only one institution said they were not interested in even discussing potential collaboration—oddly enough my own alma mater in France, Sciences Po. They said they didn’t see the need.

The second to last piece was the initial funding. I had been approached in the fall of 2013 by the Rockefeller Foundation as part of their scoping of the Big Data space, and I then talked to them about the idea. After several months of discussions, they asked how much it would take to actually set it up, and asked for a proposal. We got $400,000 in core seed funding, which for me was beyond anything I would have hoped for a few months earlier.

The last important piece was finding a space in NYC where I live—even as I am affiliated with HHI and MIT Media Lab and finishing my PhD dissertation at Berkeley. I was invited onto a panel organized at ThoughtWorks NYC in early 2014 and then asked them if they incubated non-profit start-ups. It took several meetings, but they eventually agreed to be in. Since then ThoughtWorks has been amazing to us. We ‘officially’ launched at ThoughtWorks NYC in November 2014, with the Rockefeller Foundation and most of the people who had been involved and supported us until then. But it’s only the beginning...

The second to last piece was the initial funding. I had been approached in the fall of 2013 by the Rockefeller Foundation as part of their scoping of the Big Data space, and I then talked to them about the idea. After several months of discussions, they asked how much it would take to actually set it up, and asked for a proposal. We got $400,000 in core seed funding, which for me was beyond anything I would have hoped for a few months earlier.

The last important piece was finding a space in NYC where I live—even as I am affiliated with HHI and MIT Media Lab and finishing my PhD dissertation at Berkeley. I was invited onto a panel organized at ThoughtWorks NYC in early 2014 and then asked them if they incubated non-profit start-ups. It took several meetings, but they eventually agreed to be in. Since then ThoughtWorks has been amazing to us. We ‘officially’ launched at ThoughtWorks NYC in November 2014, with the Rockefeller Foundation and most of the people who had been involved and supported us until then. But it’s only the beginning...

AR: Q2. How can Big Data further the cause of Human Rights? What have been the most prominent achievements so far in this direction?

EL: That is a central and complex question. Big Data and Human Rights are definitely linked by a “new a sometimes awkward relationship”, as the AAAS recently put it after a conference on the topic. Patrick Vinck and I spoke at that conference and we later commented on it in a blog post, saying:

EL: That is a central and complex question. Big Data and Human Rights are definitely linked by a “new a sometimes awkward relationship”, as the AAAS recently put it after a conference on the topic. Patrick Vinck and I spoke at that conference and we later commented on it in a blog post, saying:

“Big Data can help detect and fight infringements of human rights. On the other hand, the very use of Big Data can challenge core human rights—notably, but not only, privacy.”To answer your question more specifically, I think it’s useful to distinguish applications and implications of Big Data. Your question is probably about how Big Data has been or may be used to promote or safeguard some human right, which would be about applications, not so much whether it can be done in a way that is consistent with Human Rights, which would be about implications. If we focus on these applications, one initial challenge is to define what constitutes a human right. The right to life is the most fundamental—but some countries, most of them autocratic, still have the death penalty, for instance. Now, let’s assume we could all agree on a subset of basic core, no brainer, human rights,

and corresponding violations—say human trafficking, sexual exploitation, homicides, genocides, people being taken or held hostage, for example. I think Big Data—which incidentally we still haven’t really defined—can help detect and fight these abuses through relatively standard Big Data techniques: text mining and sentiment analysis, pattern recognition, predictive modeling, visualizations, etc. There are a few tangentially related examples—predictive policing in major US or UK cities for instance, which may have helped prevent a Human Rights violation (a crime for instance), and they are likely to become increasingly sophisticated, although I would be cautious about putting predictive policing (and counterterrorism) in that category.

Mark Latonero and other researchers started studying how social media data and other kinds of ‘big data’ could be analyzed to fight human trafficking as early as 2011, but to the best of my knowledge there is no clear-cut case where Big Data has been used to help dismantle a human trafficking network for instance, and that is probably very tricky to do, theoretically and technically. We could be more imaginative; for instance it may be the case and I think anecdotal evidence at least suggests, that when a big ransom is paid in a hostage situation, a change in consumption patterns of people who benefited from the money happens. Intelligence and counterterrorism agencies use Big Data a lot, and most argue that they do so to save lives, even as they spy on people. So that brings us to the other side of the coin—Big Data’s implications for Human Rights.

Take the example of the recent Ebola epidemic. A lot of people argued that telecom operators should share ‘their’ data with governments, researchers, the UN, etc., to

and corresponding violations—say human trafficking, sexual exploitation, homicides, genocides, people being taken or held hostage, for example. I think Big Data—which incidentally we still haven’t really defined—can help detect and fight these abuses through relatively standard Big Data techniques: text mining and sentiment analysis, pattern recognition, predictive modeling, visualizations, etc. There are a few tangentially related examples—predictive policing in major US or UK cities for instance, which may have helped prevent a Human Rights violation (a crime for instance), and they are likely to become increasingly sophisticated, although I would be cautious about putting predictive policing (and counterterrorism) in that category.

Mark Latonero and other researchers started studying how social media data and other kinds of ‘big data’ could be analyzed to fight human trafficking as early as 2011, but to the best of my knowledge there is no clear-cut case where Big Data has been used to help dismantle a human trafficking network for instance, and that is probably very tricky to do, theoretically and technically. We could be more imaginative; for instance it may be the case and I think anecdotal evidence at least suggests, that when a big ransom is paid in a hostage situation, a change in consumption patterns of people who benefited from the money happens. Intelligence and counterterrorism agencies use Big Data a lot, and most argue that they do so to save lives, even as they spy on people. So that brings us to the other side of the coin—Big Data’s implications for Human Rights.

Take the example of the recent Ebola epidemic. A lot of people argued that telecom operators should share ‘their’ data with governments, researchers, the UN, etc., to  help with the response—by helping model population movements for instance. The stated goal was to save lives, the most basic human right. But it wasn’t entirely clear how these data could have helped, which I think weakened the case for doing so in the heat of the crisis when sharing these data could have infringed on people’s privacy—in a number of ways—another fundamental human right. This example highlights the well-known potential tension between different human rights, the distinction between what we ‘can’ do and ‘should’ do—which is more of an ethical question—and last and the difference between applications and implications.

I think it’s possible to reconcile both, and to move forward: in the blog post I mentioned, Patrick Vinck and I wrote that

help with the response—by helping model population movements for instance. The stated goal was to save lives, the most basic human right. But it wasn’t entirely clear how these data could have helped, which I think weakened the case for doing so in the heat of the crisis when sharing these data could have infringed on people’s privacy—in a number of ways—another fundamental human right. This example highlights the well-known potential tension between different human rights, the distinction between what we ‘can’ do and ‘should’ do—which is more of an ethical question—and last and the difference between applications and implications.

I think it’s possible to reconcile both, and to move forward: in the blog post I mentioned, Patrick Vinck and I wrote that

“a political conceptualization of human rights may be the best suited to the expectations and challenges raised by Big Data. Specifically, our stance is that in modern pluralistic data-infused societies, the most fundamental human right is political participation, specifically the right and ability of citizens and data producers to weigh in on debates about what constitutes a harm (...).”We don’t say that having the rights over data about oneself is a Human Right—although it does have implications for privacy. But we do say, with others, that being allowed and able to participate in important political debates—including about the applications and implications of Big Data—is and should be treated as a Human Right.

AR: Q3. In your 2012 paper "Big Data for Development: Challenges and Opportunities", you mentioned that in order for Big Data to work for development, we need to become "Sophisticated Users of Information". Can you elaborate on that?

EL: As you point out that was in 2012—actually written in 2011—which feels like a very long time ago given the speed at which the space, and I would say my own thinking and ‘understanding’ (i.e. what I think and what I think I understand...), have changed. So what it meant then isn’t exactly what it would mean now. But first the phrase isn’t mine; it is from Jim Fruchterman—which is duly referenced in the paper. What he meant and what I meant using it was that anyone basing a decision on various pieces of information from different kinds of sources should be aware and wary of their inherent limitations–and those of the analysis and treatment they result from. In his post, Jim Fruchterman pointed to the need for “well-trained and experienced professionals in positions to make these critically important decisions.”

What he meant and what I meant using it was that anyone basing a decision on various pieces of information from different kinds of sources should be aware and wary of their inherent limitations–and those of the analysis and treatment they result from. In his post, Jim Fruchterman pointed to the need for “well-trained and experienced professionals in positions to make these critically important decisions.”

This gets to a critical issue of ‘data literacy’ in the age of Big Data. It’s easy to be fooled by compelling visualizations or fancy models. With lots of data you are always or very often going to find a correlation. But considerations for data quality and representativeness, the importance of distinguishing correlation from causation and the risks of misunderstanding or overlooking spurious correlations, all these basic statistical red flags still apply, or even more so.A classic example is the risk of basing humanitarian response in the aftermath of a natural disaster on tweets of SMSs sent and received from affected areas. It’s very

possible that the areas with the most tweets and SMS calling for help may be those least affected, because you can’t send an SMS if you are critically injured or unconscious, and because the poorest and most vulnerable people may not have cellphones to start with. So being a ‘sophisticated user’ takes a combination of technical skills in econometrics, statistics, etc., and also domain and contextual expertise, including the ability and willingness to ask for advice, and common sense.

Three years later, I would stress the importance of being sophisticated commentators and actors of and on information, and data—and what I think is missing in those areas. I think there are lots of simplistic assumptions going on about the nature and role of information and data in societies. Something I think quite strongly is that the primary reason behind why the world is in such bad shape is not lack of information. Poverty is not primarily due to a data deficit, or even a deficit of sophisticated users of information among ‘decision-makers’. I am using the term ‘among decision-makers’ because in the minds of many development experts, UN staff, and people who have spent their lives working with governments, ‘decision-makers’ tend to be equated with policymakers, governments, CEOs. There are people who have a very mechanistic view of the world—I call it Bismarckian—and think that all governments and officials are enlightened and well meaning, such that bad outcomes can only result from bad policies resulting themselves from bad or lack of information and/or poor skills. I think it’s missing a lot of what is happening and needs to happen. In a sense the data deluge has given a perfect excuse for the failures of the past: it’s because we didn’t have data!

Data are very powerful tools, and there are a lot about humans and human systems we don’t understand, and Big Data can and I think will fundamentally change our world; but part of the change will involve challenging and probably replacing the old decision-making paradigms, political processes, and power structures.

possible that the areas with the most tweets and SMS calling for help may be those least affected, because you can’t send an SMS if you are critically injured or unconscious, and because the poorest and most vulnerable people may not have cellphones to start with. So being a ‘sophisticated user’ takes a combination of technical skills in econometrics, statistics, etc., and also domain and contextual expertise, including the ability and willingness to ask for advice, and common sense.

Three years later, I would stress the importance of being sophisticated commentators and actors of and on information, and data—and what I think is missing in those areas. I think there are lots of simplistic assumptions going on about the nature and role of information and data in societies. Something I think quite strongly is that the primary reason behind why the world is in such bad shape is not lack of information. Poverty is not primarily due to a data deficit, or even a deficit of sophisticated users of information among ‘decision-makers’. I am using the term ‘among decision-makers’ because in the minds of many development experts, UN staff, and people who have spent their lives working with governments, ‘decision-makers’ tend to be equated with policymakers, governments, CEOs. There are people who have a very mechanistic view of the world—I call it Bismarckian—and think that all governments and officials are enlightened and well meaning, such that bad outcomes can only result from bad policies resulting themselves from bad or lack of information and/or poor skills. I think it’s missing a lot of what is happening and needs to happen. In a sense the data deluge has given a perfect excuse for the failures of the past: it’s because we didn’t have data!

Data are very powerful tools, and there are a lot about humans and human systems we don’t understand, and Big Data can and I think will fundamentally change our world; but part of the change will involve challenging and probably replacing the old decision-making paradigms, political processes, and power structures.

Part 2: The Role of Big Data in Economic Development

AR: Q4. How do you describe the Big Data ecosystem and categorize its major players?

EL: I’ll limit my answer to the ‘Big Data and development’ ecosystem, which is the one I know best and is actually pretty vast and complex. First and foremost I’ll say it’s a fascinating and vibrant space, both in terms of the actors and topics that animate it. It’s a mixed bag of academics, UN people, think-tank folks, researchers and managers in big private companies especially telcos... Last year I wrote a series of articles for a ‘Spotlight’ report on Big Data and development published by SciDev.Net and one of the pieces actually described the key actors in the space; I hope and think it’s still a useful resource.

Two characteristics that I would like to stress are that it’s both a highly connected and highly competitive space. It’s highly connected in the sense that if you take 15 or 20 key people—maybe even a dozen—and their institutions and their networks, you will find a lot of overlap and common ties and it creates a web that covers a good 80% of the key initiatives going on. These are people who have known and worked with each other for 4 or 5 years, sometimes more. I would call these the ‘usual suspects’ of Big Data and development, who meet at the same events several times per month sometimes.

Recently at a conference at Leiden University, Campus The Hague, the Director of the Peace

complex. First and foremost I’ll say it’s a fascinating and vibrant space, both in terms of the actors and topics that animate it. It’s a mixed bag of academics, UN people, think-tank folks, researchers and managers in big private companies especially telcos... Last year I wrote a series of articles for a ‘Spotlight’ report on Big Data and development published by SciDev.Net and one of the pieces actually described the key actors in the space; I hope and think it’s still a useful resource.

Two characteristics that I would like to stress are that it’s both a highly connected and highly competitive space. It’s highly connected in the sense that if you take 15 or 20 key people—maybe even a dozen—and their institutions and their networks, you will find a lot of overlap and common ties and it creates a web that covers a good 80% of the key initiatives going on. These are people who have known and worked with each other for 4 or 5 years, sometimes more. I would call these the ‘usual suspects’ of Big Data and development, who meet at the same events several times per month sometimes.

Recently at a conference at Leiden University, Campus The Hague, the Director of the Peace  Informatics Lab took and tweeted a photo with Bill Hoffman from the WEF, Robert Kirkpatrick for Global Pulse, Nicolas de Cordes from Orange and I, which read “Some pioneers in (big) data driven development”; I don’t know if we are ‘pioneers’—and if we are even remotely we are certainly not the only ones—and if I belong in that group, but the fact is that we have been in this space for longer than many others and know each other quite well now. There is value in this, because it has created trust, allowed and fostered partnerships and collaborations, and decreased duplications of efforts, that kind of thing. It’s hard to do something without involving the others in some way at some point.

At the same time if you look at the photo in question, you see middle-aged white males—two Americans and two French, one of whom lives in the US—and it’s actually not completely unrepresentative of the ecosystem; it’s quite male-dominated and US-centric. One of the connecting points of all of us is Sandy Pentland at MIT—our Academic Director, who also co-chairs the WEF’s Global Agenda Council on Data-Driven Development and about a dozen other initiatives, and talks to and knows everybody or almost everybody in the space. In and around the WEF Council you also find important figures—not just middle-aged white guys, too. I’d mention Danah Boyd, Kate Crawford, Juliana Rotich, for instance.

It’s also a much wider ecosystem—with people working on different facets, including human rights and ethics, for example; I’d mention Lucy Berhnolz and Patrick Ball, notably. But you still find ties there too. Of course there are parts of the ecosystem that I am less or not familiar with—and what and whom I know is biased by my own position, being in the US, interacting with these same people. But overall I still think it’s a relatively small space with a smaller nucleus, let’s say.

I also said it was competitive; it’s competitive for both personal and institutional reasons—in which I include financial. As much as we know and often appreciate each other, we also often compete for the same funding sources, try to craft a sub-space for ourselves and our organizations; there are also people with pretty strong personalities and egos in the lot, typically smart and influential—so operating in it isn't a breeze, it can be tough, frustrating. It sometimes leads to ‘sub-optimal’ sharing of information—which is sort of ironic with all the talks about the ‘data revolution’ being about transparency, etc.

But overall it’s a really exciting ecosystem and time to be in I think.

Informatics Lab took and tweeted a photo with Bill Hoffman from the WEF, Robert Kirkpatrick for Global Pulse, Nicolas de Cordes from Orange and I, which read “Some pioneers in (big) data driven development”; I don’t know if we are ‘pioneers’—and if we are even remotely we are certainly not the only ones—and if I belong in that group, but the fact is that we have been in this space for longer than many others and know each other quite well now. There is value in this, because it has created trust, allowed and fostered partnerships and collaborations, and decreased duplications of efforts, that kind of thing. It’s hard to do something without involving the others in some way at some point.

At the same time if you look at the photo in question, you see middle-aged white males—two Americans and two French, one of whom lives in the US—and it’s actually not completely unrepresentative of the ecosystem; it’s quite male-dominated and US-centric. One of the connecting points of all of us is Sandy Pentland at MIT—our Academic Director, who also co-chairs the WEF’s Global Agenda Council on Data-Driven Development and about a dozen other initiatives, and talks to and knows everybody or almost everybody in the space. In and around the WEF Council you also find important figures—not just middle-aged white guys, too. I’d mention Danah Boyd, Kate Crawford, Juliana Rotich, for instance.

It’s also a much wider ecosystem—with people working on different facets, including human rights and ethics, for example; I’d mention Lucy Berhnolz and Patrick Ball, notably. But you still find ties there too. Of course there are parts of the ecosystem that I am less or not familiar with—and what and whom I know is biased by my own position, being in the US, interacting with these same people. But overall I still think it’s a relatively small space with a smaller nucleus, let’s say.

I also said it was competitive; it’s competitive for both personal and institutional reasons—in which I include financial. As much as we know and often appreciate each other, we also often compete for the same funding sources, try to craft a sub-space for ourselves and our organizations; there are also people with pretty strong personalities and egos in the lot, typically smart and influential—so operating in it isn't a breeze, it can be tough, frustrating. It sometimes leads to ‘sub-optimal’ sharing of information—which is sort of ironic with all the talks about the ‘data revolution’ being about transparency, etc.

But overall it’s a really exciting ecosystem and time to be in I think.

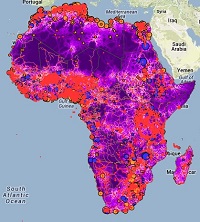

AR: Q5.Can you explain the term "Statistical Tragedy of Africa and other emerging economies"?

EL: It’s indeed a phrase I talk about quite a bit; it was coined I think by Shanta Deverajan from the World Bank in a blog post from 2011. It is a reference to the term “growth tragedy” used in the title of an influential paper published in 1997 that described what happened to Africa until the mid to late 1990s, with essentially no or negative per capita growth. What Shanta Deverajan pointed out is the lack of reliable statistics—official statistics—about Africa, and more specifically its economies and populations. As Claire Melamed from ODI and one of our co-directors wrote more recently, it’s not just or so much that there are no statistics or ‘development data’, but that “most of what we think of as facts, are actually estimates”—and they are often found out in retrospect to be pretty inaccurate.

The international statistical system is a complex animal—various UN agencies are

EL: It’s indeed a phrase I talk about quite a bit; it was coined I think by Shanta Deverajan from the World Bank in a blog post from 2011. It is a reference to the term “growth tragedy” used in the title of an influential paper published in 1997 that described what happened to Africa until the mid to late 1990s, with essentially no or negative per capita growth. What Shanta Deverajan pointed out is the lack of reliable statistics—official statistics—about Africa, and more specifically its economies and populations. As Claire Melamed from ODI and one of our co-directors wrote more recently, it’s not just or so much that there are no statistics or ‘development data’, but that “most of what we think of as facts, are actually estimates”—and they are often found out in retrospect to be pretty inaccurate.

The international statistical system is a complex animal—various UN agencies are  responsible for collecting, computing and providing statistics from various sources, including national statistical systems; sometimes the same indicator will differ between what the UN system provides and what countries provide; sometimes it will be the result of some computations, etc. When I started working at the UNDP in 2006 one of my first tasks was to conduct an assessment and overview of how the MDG (Millennium Development Goals) indicators were produced; the common analogy with the sausage-making and policy-making processes was pretty telling—you don’t want to know how it’s made.

It applies to most countries but especially to poor countries, of which there are quite a few in Africa, for obvious reasons—doing a survey is expensive, requires significant technical capacities; and it’s hard to conduct a census where there is a civil war going on. The young staffers who are well-trained and may join their national stats office will most likely soon be offered a better-paying job with the UN, an NGO, or a private company.

Hal Varian famously said years ago that the next sexiest job would be statistician—well it hasn't really happened, it’s data scientist; and quite a few statisticians are retraining and re-branding themselves as data scientists and there are no jobs for them in national stats office—yet.

This isn't a new issue, though; for decades and centuries there were only very partial economic and demographic statistics; the historical demography literature is full of great papers that have discussed and devised ways to go around lack of statistics—for instance in a lot of the literature on European development in the 16th and 17th centuries, population size over short periods of time was considered constant, for simplicity, because there was no data and because demographic growth was very slow, near zero. It changed in Europe during the industrial revolution, and then in the developing world; so estimating population size became both more difficult and more needed, because a small change in assumptions about birth and/or death rates made a big difference over a relatively short time span. Ron Lee at UC Berkeley has said that it was like “trying to hit a moving target”, almost literally. As a result though there are pretty good methods—known as indirect methods—to assess population composition and size that have been developed. What is new is the hope that perhaps ‘Big Data’ could help fix the tragedy—in full or in part. And indeed there is very promising research being done in that space and I think it will become a very hot topic.

responsible for collecting, computing and providing statistics from various sources, including national statistical systems; sometimes the same indicator will differ between what the UN system provides and what countries provide; sometimes it will be the result of some computations, etc. When I started working at the UNDP in 2006 one of my first tasks was to conduct an assessment and overview of how the MDG (Millennium Development Goals) indicators were produced; the common analogy with the sausage-making and policy-making processes was pretty telling—you don’t want to know how it’s made.

It applies to most countries but especially to poor countries, of which there are quite a few in Africa, for obvious reasons—doing a survey is expensive, requires significant technical capacities; and it’s hard to conduct a census where there is a civil war going on. The young staffers who are well-trained and may join their national stats office will most likely soon be offered a better-paying job with the UN, an NGO, or a private company.

Hal Varian famously said years ago that the next sexiest job would be statistician—well it hasn't really happened, it’s data scientist; and quite a few statisticians are retraining and re-branding themselves as data scientists and there are no jobs for them in national stats office—yet.

This isn't a new issue, though; for decades and centuries there were only very partial economic and demographic statistics; the historical demography literature is full of great papers that have discussed and devised ways to go around lack of statistics—for instance in a lot of the literature on European development in the 16th and 17th centuries, population size over short periods of time was considered constant, for simplicity, because there was no data and because demographic growth was very slow, near zero. It changed in Europe during the industrial revolution, and then in the developing world; so estimating population size became both more difficult and more needed, because a small change in assumptions about birth and/or death rates made a big difference over a relatively short time span. Ron Lee at UC Berkeley has said that it was like “trying to hit a moving target”, almost literally. As a result though there are pretty good methods—known as indirect methods—to assess population composition and size that have been developed. What is new is the hope that perhaps ‘Big Data’ could help fix the tragedy—in full or in part. And indeed there is very promising research being done in that space and I think it will become a very hot topic.

But let me add two caveats once we have described the obvious. One is that most statistics give a misleading picture of reality—it shrinks the human experience into a number, such as GDP per capita; and we have to keep that in mind. I often use Plato’s Allegory of the cave in my talks: what we ‘know’ comes from statistics that are often by definition misleading reflections of humanity, like the shadows in the cave.

Another question is whether and how not having good statistics really matters. Of course there is a strong correlation between a country’s poverty and the quality of its socioeconomic data. But is this causal? If so, in which direction? Are we suggesting that Niger would become Norway if it had Norway’s statistical apparatus, and vice-versa? Of course it’s more complicated and complex than that and no one is really saying this, but there is a bit of this undertone, as I alluded to before, that with better data we would have better policies and better outcomes, almost mechanistically. I think Norway could go on and thrive for decades without collecting any data at all. At the same time I think that if Niger had a really good statistical system it would make big progress; but in great part because of what it takes to build such a system as much as, if not more than, because of the policy impact of having good data.

But let me add two caveats once we have described the obvious. One is that most statistics give a misleading picture of reality—it shrinks the human experience into a number, such as GDP per capita; and we have to keep that in mind. I often use Plato’s Allegory of the cave in my talks: what we ‘know’ comes from statistics that are often by definition misleading reflections of humanity, like the shadows in the cave.

Another question is whether and how not having good statistics really matters. Of course there is a strong correlation between a country’s poverty and the quality of its socioeconomic data. But is this causal? If so, in which direction? Are we suggesting that Niger would become Norway if it had Norway’s statistical apparatus, and vice-versa? Of course it’s more complicated and complex than that and no one is really saying this, but there is a bit of this undertone, as I alluded to before, that with better data we would have better policies and better outcomes, almost mechanistically. I think Norway could go on and thrive for decades without collecting any data at all. At the same time I think that if Niger had a really good statistical system it would make big progress; but in great part because of what it takes to build such a system as much as, if not more than, because of the policy impact of having good data.

Part 3: Democratizing the Benefits of Big Data

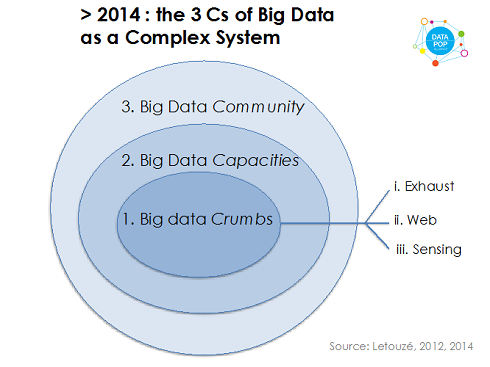

AR: Q6. What are the "3 Cs of Big Data"? Why should we care about them?

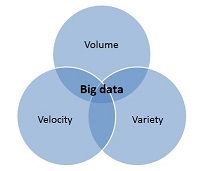

EL: The 3 Cs of Big Data is essentially a mnemotechnical framework that I developed to clarify and present my perspective on Big Data—what I think it is and what it is ‘about’. The 3Cs stand for Big Data ‘Crumbs’, Big Data ‘Capacities’ and Big Data ‘Community’; it fundamentally frames Big Data as an ecosystem, a complex system actually, not as data sources, sets, or streams. And it is both in reference to and opposition to the 3 Vs of Big Data. I’ll get to the 3 Cs in a little bit, but let me start by saying a few words on the 3Vs and why I felt we should really stop using and mentioning them altogether. Anyone who’s read a bit about Big Data is probably familiar with the 3 Vs of Big Data—Volume, Velocity and Variety—and this Venn diagram with the three eponymous sets, and Big Data being (at) their intersection. Some other people have added other Vs, for Value, Veracity, Viscosity, etc.

I always had a problem with the 3 Vs. First, I don’t think the novelty of Big Data is primarily quantitative—greater, faster; I think at the core the initial change is primarily qualitative; it is the fact that the data we are talking about are passively emitted by people “as they interact with digital devices and services” as I write regularly. In another paper, Patrick Vinck, Patrick Meier, and I described them as “digital translations of human actions and interactions”. They are non-sampled data about people’s behaviors and beliefs, and whereas you may know you are producing them and that they are going to be analyzed you don’t produce them for the analytical purposes. And it matters because focusing on the quantitative aspect suggested that it was about having and using ‘more’ information, when it’s fundamentally different information. Of course as Kenn Cukier argues a video or very many photos of a running horse is about more data generating as a result of a qualitative shift. But I would argue that every tiny bit of Big Data is different from survey data. So the bottom line is that Big Data is not about size—it’s a really bad name—I've called it “a misnomer that clouds our thinking”.

Then, I also think that Big Data is not just data—no matter how big or different it is considered to be; this is why and where I distinguish Big Data as a field—an ecosystem—and big data as data—new kinds of data. Gary King at Harvard did a presentation called “Big Data is not about the data”; what he means is that it’s also, and perhaps even more so, ‘about’ the analytics, the tools and methods that are used to yield insights, turn the data into information, then perhaps knowledge.

And so my 2nd C of Big Data, which stands for Capacities, is largely about that—the tools and methods, the hardware and software requirements and developments, and the human skills. There is an article by Kentaro Toyama that I quote often too, which talks about the importance of “intent and capacity”, about which I wrote a post about 4 years ago. The gist of this is the need to both consider and develop these capacities, without which these crumbs are irrelevant. But it’s not just about skills and chips; it’s also about how the whole question is framed. This is of course related to the concept of ‘Data Literacy’, and the need to become sophisticated users and commentators.

The 3rd C of Community refers to the set of actors—both producers and users of these crumbs and capacities. It’s really the human element—potentially it’s the whole world. As I said everybody is a decision-maker and everybody is a producer and user of data to make decisions.

I’ll get to the 3 Cs in a little bit, but let me start by saying a few words on the 3Vs and why I felt we should really stop using and mentioning them altogether. Anyone who’s read a bit about Big Data is probably familiar with the 3 Vs of Big Data—Volume, Velocity and Variety—and this Venn diagram with the three eponymous sets, and Big Data being (at) their intersection. Some other people have added other Vs, for Value, Veracity, Viscosity, etc.

I always had a problem with the 3 Vs. First, I don’t think the novelty of Big Data is primarily quantitative—greater, faster; I think at the core the initial change is primarily qualitative; it is the fact that the data we are talking about are passively emitted by people “as they interact with digital devices and services” as I write regularly. In another paper, Patrick Vinck, Patrick Meier, and I described them as “digital translations of human actions and interactions”. They are non-sampled data about people’s behaviors and beliefs, and whereas you may know you are producing them and that they are going to be analyzed you don’t produce them for the analytical purposes. And it matters because focusing on the quantitative aspect suggested that it was about having and using ‘more’ information, when it’s fundamentally different information. Of course as Kenn Cukier argues a video or very many photos of a running horse is about more data generating as a result of a qualitative shift. But I would argue that every tiny bit of Big Data is different from survey data. So the bottom line is that Big Data is not about size—it’s a really bad name—I've called it “a misnomer that clouds our thinking”.

Then, I also think that Big Data is not just data—no matter how big or different it is considered to be; this is why and where I distinguish Big Data as a field—an ecosystem—and big data as data—new kinds of data. Gary King at Harvard did a presentation called “Big Data is not about the data”; what he means is that it’s also, and perhaps even more so, ‘about’ the analytics, the tools and methods that are used to yield insights, turn the data into information, then perhaps knowledge.

And so my 2nd C of Big Data, which stands for Capacities, is largely about that—the tools and methods, the hardware and software requirements and developments, and the human skills. There is an article by Kentaro Toyama that I quote often too, which talks about the importance of “intent and capacity”, about which I wrote a post about 4 years ago. The gist of this is the need to both consider and develop these capacities, without which these crumbs are irrelevant. But it’s not just about skills and chips; it’s also about how the whole question is framed. This is of course related to the concept of ‘Data Literacy’, and the need to become sophisticated users and commentators.

The 3rd C of Community refers to the set of actors—both producers and users of these crumbs and capacities. It’s really the human element—potentially it’s the whole world. As I said everybody is a decision-maker and everybody is a producer and user of data to make decisions.

And the resulting concentric circles with Community as the larger set is a complex ecosystem—with feedback loops between them. For example new tools and algorithms produce new kinds of data, which may in turn lead to the creation of new startups and capacity needs. The basic point is that Big Data is not big data; and that questions like “how can national statistical office use Big Data” don’t mean much from my perspective—or rather they miss the point. The real important question is why and how an NSO (National Statistical Office) should engage with Big Data as an ecosystem, partner with some of its actors, become one of its actors, and help shape the future of this ecosystem, including its ethical, legal, technical, and political frameworks.

We should care about them because changing the framing, the paradigm, from one were we focus narrowly on Big Data as data with everything else being pretty much constant to a systems approach, fundamentally changes everything else—I think. I sometimes use the analogy of the industrial revolution; where you would have aristocrats and heads of governments wondering how they were going to use coal, and not realizing what was happening outside of their windows.

And the resulting concentric circles with Community as the larger set is a complex ecosystem—with feedback loops between them. For example new tools and algorithms produce new kinds of data, which may in turn lead to the creation of new startups and capacity needs. The basic point is that Big Data is not big data; and that questions like “how can national statistical office use Big Data” don’t mean much from my perspective—or rather they miss the point. The real important question is why and how an NSO (National Statistical Office) should engage with Big Data as an ecosystem, partner with some of its actors, become one of its actors, and help shape the future of this ecosystem, including its ethical, legal, technical, and political frameworks.

We should care about them because changing the framing, the paradigm, from one were we focus narrowly on Big Data as data with everything else being pretty much constant to a systems approach, fundamentally changes everything else—I think. I sometimes use the analogy of the industrial revolution; where you would have aristocrats and heads of governments wondering how they were going to use coal, and not realizing what was happening outside of their windows.

AR: Q7. Given the scope of Big Data, it is hard to ignore the Big Responsibility. However, the latter term hardly gets a fair share of conversations. What needs to be done to establish and promote ethics in Big Data?

EL: We talked a bit earlier about Human Rights—and too often ‘ethics’ and ‘human rights’ are conflated, as well as used interchangeably with the ‘responsible use of Big Data’, under a pretty vague set of ‘challenges’, ‘dark side of Big Data’, and the necessary mention of ‘privacy risks and considerations’ etc. Human rights are a legal concept, not a moral concept, although they seek to have moral validity. It is about what is just not what is considered good. Both disciplines have evolved largely in isolation from each other. The result is a lack of critical thinking at the nexus of both disciplines. It is assumed that human rights work is by definition ethical, and ethics often limited to recognizing human rights as inviolable—though most ethics code don't even mention them. What should we do with data that could promote human rights but have been acquired in an unethical way? And what is ethical, actually? The truth is that what ‘we’—different people—consider ‘ethical’ is usually undefined, and may differ a lot from one person to another.

EL: We talked a bit earlier about Human Rights—and too often ‘ethics’ and ‘human rights’ are conflated, as well as used interchangeably with the ‘responsible use of Big Data’, under a pretty vague set of ‘challenges’, ‘dark side of Big Data’, and the necessary mention of ‘privacy risks and considerations’ etc. Human rights are a legal concept, not a moral concept, although they seek to have moral validity. It is about what is just not what is considered good. Both disciplines have evolved largely in isolation from each other. The result is a lack of critical thinking at the nexus of both disciplines. It is assumed that human rights work is by definition ethical, and ethics often limited to recognizing human rights as inviolable—though most ethics code don't even mention them. What should we do with data that could promote human rights but have been acquired in an unethical way? And what is ethical, actually? The truth is that what ‘we’—different people—consider ‘ethical’ is usually undefined, and may differ a lot from one person to another.

Clearly there are entirely new ethical and legal frameworks to devise. An important question, with both ethical and legal dimensions, is who owns or should own the rights to the data that we emit. It’s not really a Human Rights question, but it has implications for privacy, data protection, and it should impact laws and regulations, but it’s clearly an ethical question, because it has implications for empowerment and equity.

Both Patrick Vinck and Sandy Pentland have thought about these issues for a long time and we really want to be actively involved in these debates. So far we have written a paper on “The Politics and Ethics of Cell-Phone Data Analytics”, organized a seminar at MIT Media Lab on these questions, and we are planning to work with AAAS on a series of outputs on Big Data, ethics and Human Rights—precisely to clarify their differences and complementarities in the age of Big Data.

But definitely, there are huge responsibilities, of all actors—but we need to clarify what they are, and to do so we need to have a sound intellectual framing. For example, the responsibility of telecom companies is not simply to give out their data—as I said I don’t think they should own all rights to all of these data they collect.

Clearly there are entirely new ethical and legal frameworks to devise. An important question, with both ethical and legal dimensions, is who owns or should own the rights to the data that we emit. It’s not really a Human Rights question, but it has implications for privacy, data protection, and it should impact laws and regulations, but it’s clearly an ethical question, because it has implications for empowerment and equity.

Both Patrick Vinck and Sandy Pentland have thought about these issues for a long time and we really want to be actively involved in these debates. So far we have written a paper on “The Politics and Ethics of Cell-Phone Data Analytics”, organized a seminar at MIT Media Lab on these questions, and we are planning to work with AAAS on a series of outputs on Big Data, ethics and Human Rights—precisely to clarify their differences and complementarities in the age of Big Data.

But definitely, there are huge responsibilities, of all actors—but we need to clarify what they are, and to do so we need to have a sound intellectual framing. For example, the responsibility of telecom companies is not simply to give out their data—as I said I don’t think they should own all rights to all of these data they collect.

AR: Q8. How do you assess the current maturity of Big Data Democratization? What would you recommend to ensure that the benefits of Big Data are accessible to the masses?

EL: It’s really the crux of the issue; to make it a democratic movement not one driven by experts and geeks hoping it will somehow trickle down to the masses. The key concepts and priorities to try and make it ‘work’ for the masses are fairly standard—it’s first and foremost about empowering them to weigh in. The Industrial Revolution and later the epidemiological transition and Green Revolution were a lot about—in the sense fundamentally shaped and driven by—social transformations resulting from people having greater agency—not just better technology. For instance better personal hygiene was key to curbing mortality rates alongside vaccines. The point is that for Big Data to serve democratic ideals broadly speaking it has to abide by and foster democratic principles and processes. A promising avenue to achieve that is human-centered design—to make sure that the systems that are developed meet the needs of communities, are built on the basis of their perspectives and needs, with their involvement.

I come back to the notion of intent and capacity—the former is about raising awareness and willingness amongst the masses to critically engage and the latter about giving them the ability, the tools, the resources to do so. It doesn’t mean turning everyone into a computer scientist—just like raising literacy didn’t mean turning everyone into writers and poets.

Creating generations with sufficiently large numbers of data literate members won’t be achieved by just teaching code at school—that will be necessary but insufficient; it’s about instilling a new data culture at all levels of societies where data is seen as a lever for social change to hold governments and corporations to greater account, debunk lies, false assumptions and fallacious arguments, to foster transparency, to improve individuals’ decision-making in their daily life too.

Concretely we are developing a training program and this is an area where I expect great needs in the next few years and decades actually.

The Industrial Revolution and later the epidemiological transition and Green Revolution were a lot about—in the sense fundamentally shaped and driven by—social transformations resulting from people having greater agency—not just better technology. For instance better personal hygiene was key to curbing mortality rates alongside vaccines. The point is that for Big Data to serve democratic ideals broadly speaking it has to abide by and foster democratic principles and processes. A promising avenue to achieve that is human-centered design—to make sure that the systems that are developed meet the needs of communities, are built on the basis of their perspectives and needs, with their involvement.

I come back to the notion of intent and capacity—the former is about raising awareness and willingness amongst the masses to critically engage and the latter about giving them the ability, the tools, the resources to do so. It doesn’t mean turning everyone into a computer scientist—just like raising literacy didn’t mean turning everyone into writers and poets.

Creating generations with sufficiently large numbers of data literate members won’t be achieved by just teaching code at school—that will be necessary but insufficient; it’s about instilling a new data culture at all levels of societies where data is seen as a lever for social change to hold governments and corporations to greater account, debunk lies, false assumptions and fallacious arguments, to foster transparency, to improve individuals’ decision-making in their daily life too.

Concretely we are developing a training program and this is an area where I expect great needs in the next few years and decades actually.

Part 4: Big Data for Development and Future Prospects

AR: Q9. In the field of "Big Data for Development", can you name a few individuals or organizations whose work you admire?

EL: I have mentioned quite a few individuals already; I think Sandy Pentland is really a pioneer in this space and has been leading and driving a lot of the discussions that are at the forefront today; I know that some of his arguments and examples—for instance those presented in his book ‘Social Physics’—may scare a few people, but he actually has a balanced and cautious perspective, in my opinion—when he talks about “saving Big Data from itself” for example or giving people greater rights over their data.

Sandy’s student Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye is doing great work—and despite his exposure he has remained humble. A few of our Research Affiliates have been especially active in the space for several years and published really good research—Linnet Taylor, Simone Sala, Bruno Lepri, and Emilio Zagheni for example.

I think DataKind, Jake Porway and Drew Conway have also done great things; I’d also mention Nuria Oliver and her team at Telefonica, Rahul Bhargava and Cesar Hidalgo at MIT Media Lab, and the work of Kate Crawford on data ethics. Evgeny Morozov, whom I have never met, is a critical and important voice too in my opinion. On the UN side apart from Global Pulse I would also mention to work of OCHA.

EL: I have mentioned quite a few individuals already; I think Sandy Pentland is really a pioneer in this space and has been leading and driving a lot of the discussions that are at the forefront today; I know that some of his arguments and examples—for instance those presented in his book ‘Social Physics’—may scare a few people, but he actually has a balanced and cautious perspective, in my opinion—when he talks about “saving Big Data from itself” for example or giving people greater rights over their data.

Sandy’s student Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye is doing great work—and despite his exposure he has remained humble. A few of our Research Affiliates have been especially active in the space for several years and published really good research—Linnet Taylor, Simone Sala, Bruno Lepri, and Emilio Zagheni for example.

I think DataKind, Jake Porway and Drew Conway have also done great things; I’d also mention Nuria Oliver and her team at Telefonica, Rahul Bhargava and Cesar Hidalgo at MIT Media Lab, and the work of Kate Crawford on data ethics. Evgeny Morozov, whom I have never met, is a critical and important voice too in my opinion. On the UN side apart from Global Pulse I would also mention to work of OCHA.

AR: Q10. What are the major projects that you are currently working on? What are your priorities for 2015?

EL: We have four main strands of work; one is a research and technical assistance program with Colombia’s National Statistical Office funded by the World Bank; another is a series of empirical research and white papers on various topics including Big Data and climate change, ethics, literacy, and methods papers; the third is a 2-year professional training program we will be launching in the summer, funded by a major philanthropic institution implemented by the MIT Media Lab; the last one is our series of events, with for instance the Cartagena Data Festival on April 20-22. We recently sent a Newsletter that describes some of these projects.

I’d say three of our big priorities for 2015-17 are ethics and human rights on the one hand—with a series of papers and events in partnership with the AAAS; and training and capacity on the other hand; in partnership with several organizations like Paris21 and SciDev.net. The needs for training are huge and it’s an area where I think we are well positioned. The third one is the development of Data Spaces—physical multi-partner and interdisciplinary collaborative spaces—in Bogotá first in 2016 and Dakar next in 2016 or 17—where we and other partners would run a lot of our activities in these regions, from training to research via events, art fairs, etc.

EL: We have four main strands of work; one is a research and technical assistance program with Colombia’s National Statistical Office funded by the World Bank; another is a series of empirical research and white papers on various topics including Big Data and climate change, ethics, literacy, and methods papers; the third is a 2-year professional training program we will be launching in the summer, funded by a major philanthropic institution implemented by the MIT Media Lab; the last one is our series of events, with for instance the Cartagena Data Festival on April 20-22. We recently sent a Newsletter that describes some of these projects.

I’d say three of our big priorities for 2015-17 are ethics and human rights on the one hand—with a series of papers and events in partnership with the AAAS; and training and capacity on the other hand; in partnership with several organizations like Paris21 and SciDev.net. The needs for training are huge and it’s an area where I think we are well positioned. The third one is the development of Data Spaces—physical multi-partner and interdisciplinary collaborative spaces—in Bogotá first in 2016 and Dakar next in 2016 or 17—where we and other partners would run a lot of our activities in these regions, from training to research via events, art fairs, etc.

AR: Q11. How can one join and contribute to the Data-Pop Alliance initiative? Are you looking for contributors with any particular skills?

EL: We are working out a strategy for people to be able to contribute in a more structured manner; we will be developing a blog post series to which we’d like people to be able to send submissions on key topics; we are also developing thematic working groups or ‘Data Nodes” animated by our network of Research Affiliates in which external people and groups will be able to participate.

And we will offer positions as funding becomes available for specific projects. We have too much to do so really all help is welcome. We are also developing a process for people to become Research Affiliates, and a proper internship program. But all of this takes time if you want to do it well.

The nature of our activities is to be very multidisciplinary—or ‘anti-disciplinary’ as the MIT Media Lab characterizes itself. We need people with data science skills, econometrics skills, writing skills, and communication skills. Above all, we need and will seek people who are driven, motivated, creative, humble, who have a collaborative spirit and are not afraid of taking a bit of risk in their careers.

EL: We are working out a strategy for people to be able to contribute in a more structured manner; we will be developing a blog post series to which we’d like people to be able to send submissions on key topics; we are also developing thematic working groups or ‘Data Nodes” animated by our network of Research Affiliates in which external people and groups will be able to participate.

And we will offer positions as funding becomes available for specific projects. We have too much to do so really all help is welcome. We are also developing a process for people to become Research Affiliates, and a proper internship program. But all of this takes time if you want to do it well.

The nature of our activities is to be very multidisciplinary—or ‘anti-disciplinary’ as the MIT Media Lab characterizes itself. We need people with data science skills, econometrics skills, writing skills, and communication skills. Above all, we need and will seek people who are driven, motivated, creative, humble, who have a collaborative spirit and are not afraid of taking a bit of risk in their careers.

AR: Q12. What is the best advice you have got in your career?

EL: “Be only yourself but don’t only think about yourself”—it’s something my grandfather told me once when I was a child. It sounds a bit empathic but it struck me, because he was a role model, and it stuck with me. It has turned out to be a great piece of advice, one I would give to anyone starting to work: be altruistic and cooperative, have and show empathy, work for and with others, and work hard, carry your weight, don’t slack, because if you do someone will have to do the work; be trustworthy; ask questions to people and care about them, put yourself in their shoes as much as possible, try to help out.

We are social animals, and the group is stronger than any given individual. How your peers and colleagues and partners perceive you will determine almost everything in your career. What I have found is that eventually, people know if you are real or fake, if you can be trusted or not, if you deliver or flake, if you have a spine or are full of air, if you plagiarize or give credit, if you have hidden agendas or talk straight. People always find out. There are of course people in the Big Data space who I think have an unwarranted credit and influence, and are thinking primarily about themselves and their personal brand, as in all fields; but over time people do realize.

If you want to succeed, you will need people to support you, and for people to do so you will need to demonstrate you are worth supporting. And that may mean working long hours, accepting a pretty bad salary or a short–term contract, if you think the people you work for deserve your trust. Because it has to be reciprocal. If someone fails me or reneges on a promise, I’m out. That’s the ;“be only yourself” part.

EL: “Be only yourself but don’t only think about yourself”—it’s something my grandfather told me once when I was a child. It sounds a bit empathic but it struck me, because he was a role model, and it stuck with me. It has turned out to be a great piece of advice, one I would give to anyone starting to work: be altruistic and cooperative, have and show empathy, work for and with others, and work hard, carry your weight, don’t slack, because if you do someone will have to do the work; be trustworthy; ask questions to people and care about them, put yourself in their shoes as much as possible, try to help out.

We are social animals, and the group is stronger than any given individual. How your peers and colleagues and partners perceive you will determine almost everything in your career. What I have found is that eventually, people know if you are real or fake, if you can be trusted or not, if you deliver or flake, if you have a spine or are full of air, if you plagiarize or give credit, if you have hidden agendas or talk straight. People always find out. There are of course people in the Big Data space who I think have an unwarranted credit and influence, and are thinking primarily about themselves and their personal brand, as in all fields; but over time people do realize.

If you want to succeed, you will need people to support you, and for people to do so you will need to demonstrate you are worth supporting. And that may mean working long hours, accepting a pretty bad salary or a short–term contract, if you think the people you work for deserve your trust. Because it has to be reciprocal. If someone fails me or reneges on a promise, I’m out. That’s the ;“be only yourself” part.

AR: Q13. What was the last book that you read and liked? What do you like to do when you are not working?

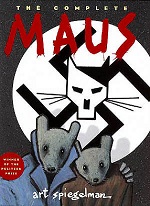

EL: It’s a book I re-read, or re-re-re-read; it’s Maus, the comic strip by Art Spiegelman. I also do political cartooning and I was on a panel with him at the French Institute a few weeks ago after the Charlie Hebdo attacks; I was invited because I had done a tribute comic strip for Medium about the cartoonists who were killed that I had met as an aspiring cartoonist in France during my studies almost 20 years ago. Art Spiegelman is of course one the greatest living cartoonists and meeting him was a bit surreal; I brought my old copy of Maus to the event, in two volumes and in French, and after talking to him for about 20 minutes backstage I found the courage to ask him whether he could sign both—one for me and one for my father. He accepted and since then I read it again; and am still very moved by it, even more so now than I was the first time because it carries this additional symbol.

EL: It’s a book I re-read, or re-re-re-read; it’s Maus, the comic strip by Art Spiegelman. I also do political cartooning and I was on a panel with him at the French Institute a few weeks ago after the Charlie Hebdo attacks; I was invited because I had done a tribute comic strip for Medium about the cartoonists who were killed that I had met as an aspiring cartoonist in France during my studies almost 20 years ago. Art Spiegelman is of course one the greatest living cartoonists and meeting him was a bit surreal; I brought my old copy of Maus to the event, in two volumes and in French, and after talking to him for about 20 minutes backstage I found the courage to ask him whether he could sign both—one for me and one for my father. He accepted and since then I read it again; and am still very moved by it, even more so now than I was the first time because it carries this additional symbol.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)