DISCUSSION PIECE

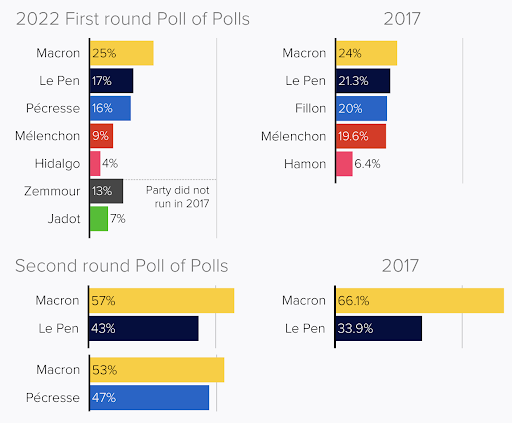

In France, between April 10 and 24, 2022, two rounds of the presidential elections will be held to determine the next tenant of the Elysée. Months before the election, the euphoria surrounding the upcoming election is already palpable. The media outlets are trapped in horse-race reporting, touting a new poll every single day. The presidential race monopolizes every TV set, with the exception of new COVID-19 variants occasionally taking center stage. It is in this hysterical political context that I, a French citizen, will vote in the presidential election. I will be exercising this right in a France that has seen the breakthrough of the extreme right-wing candidate Eric Zemmour, in opposition to two other far-right candidates; in a France preoccupied with debates on migration issues, insecurity, and national identity; in a France with a rhetoric dominated by fear and division. I thus sought to understand in this article why these questions were so prominent in this context: are they really the issues that concern French citizens the most?

To do so, I followed the same approach as political leaders, namely to feel the public pulse. I explored the realm of opinion polls, a primary factor in driving the political debate. Governments, political candidates, and journalists use them to quantify, direct, and control citizens’ opinions; determine what constitutes relevant news, and adjust the electoral program. In France, these polls have grown in influence: in 2002, 193 surveys were published during the presidential race versus 560 in 2017 (Bronner, 2021). Public opinion polls are everywhere, and yet they remain controversial. The development of polling techniques has made the evaluation of public preferences a form of knowledge in French society and of its concerns and has become an indispensable instrument of measurement for the exercise of democracy.

But as polling organizations “perfect” their methods, the limits of polls are increasingly brought to light. It is important for people to understand how they work, and how opinion data is produced, to really appreciate what they actually show.

Understanding Political Opinion Polls

Opinion polls are largely defined as the “aggregation of privately held individual opinions as revealed through carefully constructed questions posed to randomly selected samples” (Goidel, 2011). They are widely used in political science and other fields to study the behavior of voters (Shapiro, 2015). Polling firms insist on the scientific nature of their methodology to collect data to adequately represent public preferences. Public opinion institutes aim to capture the political will at a given moment, rather than predict the outcome of the election months or weeks before.

The birth of opinion polls, in 1938 in France, coincided with the development of a mass culture of communication, feeding the emerging culture of immediate consumption (Goidel, 2011). Institutes previously conducted face-to-face or telephone polls, but as people have exchanged their landlines for cell phones, online interviews are now more common. The economic benefit of self-administered surveys is clear: institutes no longer have to hire investigators. However, this evolution illustrates the decline of response rates: 50 years ago, nearly half of those called might participate, today it is down to 5 percent, and the number is even lower for politically-related questionnaires (Hartman, n.d.).

How do Opinion Polls Work?

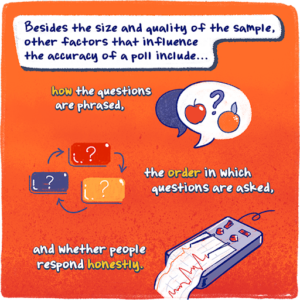

Pollsters take great care in both the phrasing of questions and to ensure representativeness, which are the first requirements of a trustworthy poll (American Historical Association, n.d.). To accurately reflect the opinions of the whole population, polling firms can choose a large and genuinely random sample. But a large sample selected thoughtlessly may result in a larger error than a smaller sample selected appropriately (American Historical Association, n.d.). Instead, pollsters use quota sampling, corresponding to a sample of individuals that will represent the population as a whole (BBC, 2016), involving the right balance in the place of residence, the type of housing, the standard of living, gender, age, level of education, and religion.

It is, however, time-consuming and costly to interview random people willing to respond. Pollsters increasingly struggle to obtain representative samples, thus undermining the credibility and reliability of the polling data (Goidel, 2011). To overcome these barriers, public opinion institutes contact members of their own database or panel (Bronner, 2021). Adjustments or weightings are then made as needed. Through sociodemographic adjustments, pollsters give more weight to underrepresented groups. For adjustments related to political polls, respondents are asked about their votes in previous elections to assess whether the aggregate of votes matches the final election result. For instance, if the number of respondents who voted for Emmanuel Macron in the previous presidential election is higher than his final score, the analyst will then proportionally reduce the weight of their responses to align with reality. An adjustment, in theory, guarantees better representation, but given that each analyst is free to change the weight of respondents, this can lead to very different final results, especially for pre-election surveys (Clinton, 2021). Pollsters finally set up a margin of error or confidence interval, which provides a reasonable assessment of the compatibility with nationwide surveys.

Who Commissions Polls?

Although the myth exists that politicians do not pay much attention to opinion polls, the reality is quite different. Some opinion polls are conducted by independent institutes and others by media organizations. Yet, in both cases, they are usually commissioned by a political party, lobbying organization, or interest group who expects to publish the result if the responses are to their satisfaction (BBC, 2016). On the other hand, politicians scrutinize the outcomes of other published polls to guide their decisions, or in pre-election periods, to guide their rhetoric.

Political polls undoubtedly help shape political agendas and messaging strategies. Opinion polls also serve the media. Around elections, “horse race” stories are a mainstay of election coverage. Every time a poll is released showing the candidates’ advance or decline, journalists comment and speculate. Candidates who are doing poorly in the polls don’t get much coverage, while the leading candidates receive much more airtime.

The Challenge of Measuring Public Opinion in the Digital Age

The 2022 French presidential campaign, more than any previous contest, takes place in digitalized society where the use of social networks by both candidates and voters is pervasive and ever increasing. The emergence of new technology has thus shaken up the polling industry, as pollsters struggle with significant challenges to the credibility of their surveys. Paradoxically, the increasing reliance on and demand for polls to capture public opinion are set against a backdrop of distrust in the quality of their data. With the widespread adoption of digital media, the information available to citizens has not only increased, but so have opportunities for political participation and expression of opinion. In this environment, the political conversation is ongoing and incomplete (Goidel, 2011). Public opinion in the digital age may be more elusive and therefore less easily measured than before. By definition, opinion polls propose to aggregate individual preferences to evaluate the collective sentiment, but in a changing digital society, it is now very difficult to comprehend a public that has become very dynamic and interactive.

What are the Controversies Around Opinion Polling?

Technical Arguments

Opinion polls have been criticized for inconsistencies in their operations. Michel Lejeune, in his book “La Singulière fabrique des sondages d’opinion,” denounces the artisanal and non-scientific dimensions of polling. To begin, the identities of the participants can be fake, as can their answers, or they also can participate in several surveys. In response to these potential issues, institutes provide assurance that there are systems for verifying the authenticity and the number of participations per respondent. For instance, to verify identity, tricky questions are sprinkled throughout the questionnaire. However, in an attempt to test those strategies, the French journalist Luc Bronner created several identity profiles and was able to take 4 questionnaires a day for the same institute (Bronner, 2021). In addition, panels are supposed to be random, but institutes still call for volunteers through advertising: using self-selected samples results in a sampling error and therefore an unrepresentative poll. Moreover, polling firms have difficulty in anticipating the abstention rate. They have already experienced failures in the 2021 regional elections when they predicted a turnout of 40% (which in reality was 33%) and overestimated the vote in favor of the extreme right-wing candidates. It should be noted, however, that during the 2017 presidential campaign, institutes managed to predict the arrival order of the main candidates in the closing stretch.

Economic Arguments

Public opinion institutes have also been accused of being “marketing research companies” rather than scientific institutes. This is because they only respond to requests from the media and political companies. Moreover, behind the online surveys, a business models exists in which the decreased cost of survey creation, coupled with the intrusive increase of the data collection and shortened analysis times inevitably lower the quality of the final data. This would be a win-win situation, as the media gets editorial content and the institutes get visibility.

Political Arguments

Detractors highlight the suspicious voluntary participation of respondents on online surveys, where it is likely that people with deeper political convictions will be most willing to respond. Public opinion polls, therefore, exclude a significant swath of the population, namely the moderate or the undecided voters, who do not have any particular political orientation (Goidel, 2011). In addition, despite the existence of a Commission des Sondages (Polling Commission), which has monitored every published opinion poll since 1977, some are still not entirely reliable. But it is not the polls that should be blamed for the poor political debate, but rather those who do not distinguish “good” from “bad” data collection methods and misinterpret them. Political journalists have the ability to influence the narrative of political campaigns and shape the contours of the debate, thus data literacy amongst this group is vitally important.

Philosophical Arguments

A person should not have an interest in replying for the sake of representativeness, but can a disinterested person have meaningful conversations on technically complex topics? One may then view survey responses as mostly non-opinions disguised as meaningful public engagement. As a result, opinion polls would transform a passive form of citizen participation into a political commitment, whereby opinion has been incorrectly defined as the aggregate total of private beliefs.

Do Opinion Polls Protect or Harm Democracies?

Placing ourselves in the pre-electoral context that France is experiencing, is of utmost importance to understand whether polls in the digital era threaten or enhance democracies. To do so, I asked myself three questions which I attempt to answer in the following section:

Is French Public Opinion Becoming More Radical?

Extreme-right candidates constantly gain points in the voting intentions, revealing a form of radicalization in French society. This may or may not be an accurate representation of the reality on the ground, depending on if “hidden” voters are now allowed to reveal their true sentiments, or if highly political respondents are skewing results. The heavy dependence on online methodology accounts for respondents no longer fearing judgment when saying they will vote for extreme candidates. During face-to-face or telephone interviews, people were far less likely to tell the truth about their political opinion, resulting in the underestimation of votes towards Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002. Nonna Mayer and Vincent Tiberj conducted a survey under the “Commission nationale consultative des droits de l’homme” (CNCDH), revealing a 20 points difference between questionnaires conducted simultaneously. One was a face-to-face interview while the other was conducted online, with the latter collecting more radical answers. However, the voluntary aspect of participation is a bias in itself. In theory, random survey respondents should have no particular interest in participating. Therefore, one can assume that those who do participate are either interested (political activists) or are people with very strong (and even radical) opinions. As a result, despite the adjustments made, a more radicalized picture of French society can emerge from a survey.

As Opinion Polls Tend to Take a Radicalized Snapshot of Society, are non-Radical Citizens Likely to be Influenced?

Honestly, I expect people to have stronger convictions than beliefs in prediction curves. But my main concern is the overinterpretation of these curves. The rise of extreme candidates in the polls is not a danger in itself, but rather the resulting headlines that may influence public opinion by framing the political debate around the priorities set by those extremists. This is why in France, there is increasingly fierce debate around topics such as migration or national identity, which help foster a hostile and anxiety-provoking atmosphere. In addition to the misuse of polls, more measurements collected on a societal phenomenon may explain the perceived radicalization of society.

While we have the Ability to Better Understand Social Phenomena Through Data, Why is Data-based Storytelling not Convincing?

It’s a matter of trust. People easily delegate their knowledge to others when it comes to hard skills by agreeing to be operated on by a surgeon, or by agreeing to drive a car designed by an engineer. However, this cooperation and delegation of knowledge are challenged when it comes to soft skills, especially in the political domain. Somehow, in politics, people tend to “ignore facts” (Kolbert, 2017). The rise of political opinion polls does not stand up to ultracrepidarianism or confirmation bias. In their book “The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone”, Slomane and Fernback theorize that “strong feelings about issues do not emerge from deep understanding”. In other words, they denounce the “illusion of explanatory depth,” the belief that you think you know more than you actually do. In 2014, shortly after Russia annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea, they conducted a survey, asking respondents how they thought the United States should respond, and whether they could identify Ukraine on a map. The result was that the further away they were from the geography, the more likely they were to favor military intervention (Slomane & Fernback, 2017). Consequently, whether it is random citizens answering technical questions in polls, or journalists publicly debating subjects on which they have little knowledge, ultracrepidarian people encourage the deviation of public opinion towards radicalization, moving away from the data. In addition to the lack of ability to recognize one’s ignorance, the increasing cooperation and communication in the digital age reinforce each other in the supposed “truthfulness” of their convictions. This tendency to embrace information that supports one’s belief and reject those that contradict them is called confirmation bias. When a person agrees with me, his or her opinion (despite being baseless) gives me more confidence in my opinions. Convinced that this is the right answer, we reject all other arguments that don’t align, and form a minority of radical people, closed to debate and convinced of our righteousness. This is how a community of knowledge can become dangerous.

Conclusion

Originally created to serve democracies, the massive increase of political polling tends to influence opinions rather than capture societal dynamics, and yet, polls clearly remain the dominant form for representing collective preferences. Thus, analyzing them helps us understand why they must be implemented and utilized with great precaution, as not to negatively impact democratic societies. To me, a young voter and professional recently delving into the data and political landscape, polls should exert a similar influence on the public as that of any book or tweet, and only attempt to stimulate discussion of current events. One can hold to account opinion polls for shaking up and radicalizing societies, but even if they were to be abolished, social networks would still allow for negative passions to shape public opinion. If we really want to get a sense of what people are thinking, citizens, candidates, and political journalists should spend less time sharing extreme or inaccurate views and data, and more time trying to truly understand the public pulse. Let’s hope that the next weeks in France will favor this type of moderation and nuance!

About the author: Bertille Kerouault is a Research and Content Intern at Data-Pop Alliance. She is studying at Sciences Po Paris as an undergraduate student specialized in economics and international finance.

References

- American Historical Association. (n. d.). How Are Polls Made? Accessed on January 21, 2022: https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/gi-roundtable-series/pamphlets/em-4-are-opinion-polls-useful-(1946)/how-are-polls-made

- BBC News. (2016). Q&A : How do opinion polls work? https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-35350361

- Bronner, Luc. (2021). Dans la fabrique opaque des sondages. Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2021/11/04/dans-la-fabrique-opaque-des-sondages_6100879_823448.html

- Clinton, Joshua. (2021). Polling Problems and Why We Should Still Trust (Some) Polls. Vanderbilt University. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/unity/2021/01/11/polling-problems-and-why-we-should-still-trust-some-polls/

- Goidel, Robert K. (2011). Political Polling in the Digital Age : The Challenge of Measuring and Understanding Public Opinion (Media and Public Affairs).

- Hartman, E. (n. d.). Knowing the Vote. TECHER. Accessed on January 21, 2022: https://www.alumni.caltech.edu/techer/knowing-the-vote

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. (2017). Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/02/27/why-facts-dont-change-our-minds

- Shapiro, Robert Y. (2015). Opinion Poll—An overview | ScienceDirect Topics. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/opinion-poll

- Sloman, Steven and Fernbach, Phillip. (2017). The Knowledge Illusion : Why We Never Think Alone.