DATA FEMINISM PROGRAM

A Brief History of Feminism

It is somewhat difficult to pinpoint the “beginning” of feminism, and when exactly the application of gendered lenses became an instrumental tool for the advancement of women’s rights around the world. The literature commonly refers to the modern feminist movement as occurring in three main waves, with some scholars suggesting that a fourth wave is currently in progress. Olympe de Gouges, Wollstonecraft, Jane Addams, de Beauvoir, Gloria Steinem, Frida Kahlo, Angela Davis, bell hooks, Judith Butler, Maya Angelou, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie are just some of the hundreds of names famously associated with the diverse agendas and movements within feminist history. In any case, it is important to note that there are fundamental differences between these waves of feminism, and that these differences have been instrumental in shaping what we now understand as “Data Feminism”.

The first feminist “wave”, which spanned from the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, focused primarily on advancing political rights and securing women’s right to vote. This wave was mostly active in the Western world, and many terms have been used to distinguish this important, but controversial, movement. Authors such as Koa Beck have referred to it as “white feminism”, while other terms have been used to capture this wave’s primary focus, such as Western feminism, corporate feminism, bourgeois feminism, and girl-boss feminism. The controversy stems from it being viewed as an exclusionary movement which does not (necessarily) embrace or advocate for women’s rights from an intersectional perspective, but rather work towards the advancements of the rights of white, middle- to upper-class women within Western capitalist systems. It was not until the second wave of feminism that Black women began to have greater participation in and impact on the movement, an injustice that was influenced by institutional racism of the time period (Wilson, 1997).

The so-called “white feminism” essentially pursues equal rights for those women within the culturally dominant elite of Western societies. They often had access to the best universities, a secure (yet arbitrary) number of years of professional experience, and financial resources. What binds them together is this “aspiration to whiteness”, or to gain more full participation in societies where white men traditionally held most of the political, economic and social power.

The importance of understanding the context of this first wave of feminism is that it opened the space for other voices to emerge, due to the (compounded) inequalities that other (non-white) groups of women face. Specifically, activists such as Kimberlé Crenshaw, Audre Lorde, and Angela Davis began advocating for more intersectional approaches to understand, reflect, and move forward with a more egalitarian idea of what feminism is and could be. The term “intersectionality” was coined by Crenshaw, and is rooted in the concept of “interlocking” systems of oppression —that is, “we are actually living at the intersections of overlapping systems of privilege and oppression” (Carty and Mohanty, 2019). Intersectionality does not see women as a homogeneous group, but rather as one that encompasses several characteristics that, when combined, can enhance (or diminish) the level of inequality and marginalization they face, such as race, class, religion, national origin, or disability, amongst others.

Intersectionality, therefore, is at the core of DPA’s Data Feminism Program. We seek to build knowledge and foster awareness on gender inequalities worldwide by questioning how the types of inequalities faced by women (and other gender diverse minorities) intersect in given contexts. To gain the fullest understanding of this issue, as with all our work, the role of quality data is a vital component.

The Development of DPA’s Conception of Data Feminism

Our modern societies, with their instantaneous connectivity and ability to share information, are a product of the advances achieved by the combination of technology and the efficient use of data. However, just as data allows us (NGOs, researchers, policy makers, advocates and activists) to reach important conclusions about inequalities, action points, and needs of marginalized populations, data can also segregate and further increase hardships experienced by these groups, which very often includes women, girls and other gender minorities. As highlighted by leading thinkers and practitioners on gender data, such as Data2X, Open Data Watch, Ladysmith, A+ Alliance, and UN Women, major barriers still exist in the collection and use of data that highlights the unique experiences of women and girls. This lack of data (or data gaps) hinder our ability to truly understand the lived experiences of women and girls, to design successful interventions that improve their living conditions, and to monitor changes and transformations that contribute to the ultimate goal of achieving gender equity (Goal 5 of the Agenda 2030 for the Sustainable Development Goals.

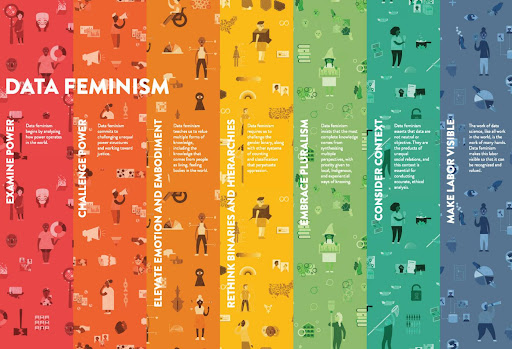

Not only is the availability of gender data often insufficient, but there are also glaring flaws in current research methodologies and technical measurement. These shortcomings have led to inaccurate and incomplete information on the status of women and girls worldwide. Some of these problems include inherent biases and prejudices in the way data is collected and interpreted, leading to the emergence of what we call “Data Feminism”. The term was coined by By Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren F. Klein in their homonymous book, which represents a genuine revolution in the way data science and data ethics is perceived, carried out and used to inform the feminist agenda. Data Feminism is underpinned by seven key principles (pictured below), which in turn should be considered to ensure the equal visibility and application of the concept of feminism within the gender data landscape.

As the authors express, Data Feminism is not only about or for women. Data feminism is about power, challenging those who hold it and empowering those who have been left out of traditional power structures. This is what Data Feminism means for DPA. In this sense, our Data Feminism Program’s goal is to produce evidence for advocacy endeavors and policies that will accelerate intersectional, feminist, and LGBTQI+ inclusive gender equality. Our Program has four main products through which we seek to provide a clear diagnosis of gender issues and gaps, and effective guidelines to direct efforts towards advancing gender equity:

1) Mixed-Methods Evidence-Based Assessments;

2) Gender and Data Capacity-Building;

3) Advanced Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Data Modeling and Visualization;

4) Mapping and Assessment of Technological Solutions for Gender Equality.

Each of these products seeks to contribute solutions to a specific challenge, with the ultimate goal of improving the availability, quality, and use of gender data through an intersectional feminist perspective.

What Data Feminism Means for DPA’s Work

Based on DPA’s three pillars of work, our goal for the coming months and years is to continue contributing to a gender data ecosystem that is not exclusionary or biased (more on that soon!), but one that integrates all the characteristics, experiences, and perceptions of the heterogeneity of “gender”, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 5. These pillars are:

- DIAGNOSE. Research on gender issues, particularly in countries of the Globe South. We will continue leveraging feminist, intersectional and LGBTQI+ inclusive knowledge and awareness to identify pressing and specific issues, how they are connected, and how they can be overcome through evidence-based recommendations. Although we currently have the most experience on issues related to gender-based violence, our objective is to expand beyond this scope, including work on issues related to sexual and reproductive health and rights (including HIV prevention); the intersection between women and climate change; migrant and refugee women and girls; gender-non conforming individuals, among others.

- MOBILIZE. The collection and use of Gender Data and the skills sets necessary to produce evidence from them. Through our consolidated expertise in capacity building activities, DPA will continue developing trainings to foster gender and data mainstreaming and literacy of individuals and organizations, in order to build the data skills needed to lead gender-responsive advocacy work. With our Gender Data 201 course as a prime example, our goal is to design additional courses tailored to the specific needs of institutions (including by field / thematic priority and technical capacity), as well as free courses that allow more individuals to become informed about how gender data can be leveraged to advance gender equality.

- TRANSFORM. The reality of women, girls and gender minorities by leveraging the use and improvement of technologies and AI. In the last year, we have been developing and combining modern techniques and AI-based features (including machine learning), to create increasingly accurate and intelligent models that allow us to better understand the factors that affect the prevalence and reporting of GBV, and the ways in which (and to what degree) they do so. Through these initiatives and studies, our goal for the near-future is to create a digital platform that will allow us to visualize up-to-date GBV incidence in countries highly affected by this epidemic (i.e. Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and MENA region), as well as an estimation of underreporting rates that take into account individual and contextual factors affecting women’s capabilities to report.

If you are interested in learning more about our Data Feminism Program, click the button below to find out more. If you’d like to join us on this journey, either by learning more, contributing financially or collaborating, please reach out to: aspinardi@datapopalliance.org or iyanez@datapopalliance.org.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)