DISCUSSION PIECE

Mining in Latin America: From Colonization to Open Markets

“Even if all the snow in the Andes turned to gold, still they would not be satisfied”.

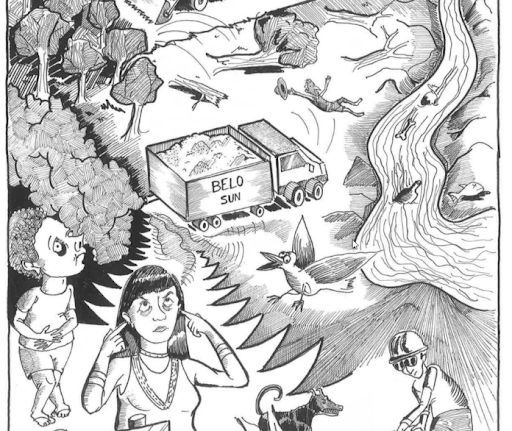

Six centuries after Inca leader Manco Capac’s famous quote in reference to Spanish colonization in the Andean region, the exploitation of natural resources destined for export remains alive and well in Latin America. Extractive operations can be defined as acts that exploit or ‘extract’ raw materials from the Earth, often involving mining, gas, oil, and timber industries, among others. While extractive projects may also involve artisanal small-scale mining, “extractivism” refers solely to the mining operations within the dominant capitalist economy, the latter being the focus of this piece.

The territories now recognized as Latin America suffered from over three centuries of Spanish and Portuguese colonial rule, with records of commercial resource exploitation in the region dating back even farther, to the early 16th Century. After the violence of colonization, characterized by slavery, ethnic cleansing, and genocide of Indigenous peoples, most countries in the region faced major instabilities in their political consolidations, followed by years of military dictatorships and recurrent coups.

In the 21st century, economic reforms were implemented all across Latin America, following the regional debt crises in the 1980s. These reforms led to widespread “openings” (or deregulation) in the international market, based on recommendations from the Washington Consensus. During such openings, many concessions were made to foreign companies, a considerable part of them being large-scale development projects, thought to be an opportunity for economic growth. For the multinational mining sector, this meant that governments would grant access to areas rich in minerals and allow private foreign companies to extract and commercialize natural resources (which had previously belonged to the state). These initiatives promised development through the generation of tax revenue, dividends for shareholders, and employment for the local population. In exchange, they were given the green light to explore abundant mineral reserves. However, evidence shows that extractive industries often fail to deliver on these promises, and instead increase social, economic, and gender inequalities, while also causing harm to the environment.

The economic openings in the 80s resulted in significant episodes of civil unrest, motivated by the harmful impacts wrought by the multinational mining companies. These impacts included cases of water and air contamination, as well as Indigenous land expropriation and violence. While extractivist development operations viewed territory in terms of profitability (from extraction of resources), indigenous communities had ancestral spiritual and cultural bonds with the land, expressed through long-standing subsistence practices.

Conflicts Over Land and Resources: Indigenous Communities vs. Governments and Private Mining Companies

Many present-day Latin American countries claim to acknowledge the rights of Indigenous people to the lands they have traditionally occupied. This is usually done through the demarcation of said territories; a judicial recognition that is often endorsed by the constitution, as it can be seen in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Unfortunately, these rights are often overlooked, because when it comes to the territorial grants to extractive industries, governments claim use over the land for the public interest, arguing that they are beneficial to the surrounding communities and to national economic growth. This has caused several social uprisings and protests in response to large companies appropriating water reserves, small-scale farming fields, and territories used for housing. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples clearly states that Indigenous communities shall not only participate in decision-making of matters which affect their rights, but also that they must be consulted by the States prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands, territories, and resources (Articles 18 and 32). However, only 39 consultations have taken place in the region during the past decade, despite there being 301 extractive projects identified in Latin America during this time period.

From 2001 to 2021, 284 mining-related conflicts were reported, 162 of which were linked to freshwater pollution and expropriation. Currently, the Latin American countries with the highest rates of mining-related conflicts are Mexico (58), Chile (49), Peru (46), Argentina (28), and Brazil (26). These often involve police, paramilitary groups, and national governments pitted against campesinos (the Spanish word for Native people who live off the land), who are supported by human rights and environmental activists. According to OCMAL (2021), 264 cases of state criminalization against anti-mining protests have been reported in the last decade, while 42 female human rights and environmental activists have been criminally charged. The most frequent accusations against activists include claims of public-road obstruction, disturbances, aggravated damage, and sabotage.

In 2020, Global Witness recorded 227 deadly attacks against environmental defenders worldwide, 72.6% of which occurred in Latin America. At least 30% of such attacks were directed towards activists who fight against natural resource exploitation. These figures are likely an underestimate, as the COVID-19 pandemic impacted investigation capabilities in remote areas, in addition to threats, surveillance, criminalization, and sexual violence contributing to the underreporting of attacks. However, brave women across Latin America continue to fight against expropriation and pollution, even in the face of threats, lawsuits, criminalization, and even death.

The Impacts of Multinational Mining Projects on Women

Studies have shown that mining activities’ consequences on livelihoods and the environment disproportionately affect women. According to the Collective on Socio-Environmental Actions Coordination (CASA, 2016), water and wind contamination (caused by extractive processes) considerably affects women’s everyday lives, as they are often responsible for their family’s food and water provision, livestock care, and small-scale farming activities. The water contamination caused by spreading and/or dumping of toxic material discarded from mineral extraction not only contributes to food and water scarcity but also has toxic effects on breastmilk, making it harmful for mothers and children alike. Because young children’s health is particularly vulnerable, they can easily become ill from this contamination. Additionally, women’s workloads related to child-care and food provision are also impacted, therefore worsening their mental and physical health.

Moreover, with the growing presence of male workers from outside the community, insecurity and fear become a part of women’s everyday lives, as cases of physical and sexual violence against Indigenous women are commonly reported around extraction sites. One pertinent example is that of the Fénix Project, undertaken in territories belonging to the Mayan Q’eqchi community in Guatemala. Claims of sexual abuse committed by military and security personnel dressed as workers from the Canadian mining company Hudbei were reported by 11 women during the mass evictions carried out to allow for the project.

Female Human Rights and Environmental Activism in Latin America

As female activists who defend human rights and the environment actively oppose extractive industries, they are especially targeted and threatened by the sector’s corporate power and the governments that uphold it. When intersecting with race and ethnicity, threats and violence against women become even more aggressive. Those within these intersections (i.e. Black Indigenous women) must not only confront corporate power, but also the deeply-rooted patriarchal structures, historical class privilege, and racism embedded within such extractive activities.

Violence against women activists has been reported extensively across the region. In 2016, Peruvian local farmer Maxima de Acuña, whose family refused to sell their land to a mining company, was physically assaulted by attackers, allegedly hired by that same company. Maxima was left unconscious near the Yanacocha mining project which she fiercely advocated against for several years. Other than physical violence, the Peruvian activist has had her home demolished and crops destroyed by Yanacocha’s armed security officers. Yet, this Campesina continues to defend her community’s health and wellbeing in the face of the environmental consequences of the extractive industry.

In 2019, the Brazilian environmental human rights activist Rosane Santiago Silveira was brutally tortured and murdered in her home. She had fought against extractive activities within environmental reserves in the states of Bahia and Minas Gerais and contributed to the creation of sustainable food production and distribution practices in Brazilian federal universities. Similar cases can be found in other countries across the region. In Colombia, Afro-Colombian activist Francia Márquez has received death threats and murder attempts for defending her community’s ancestral territories from gold mining. In 2014, Francia led a 22 day walk, in which 80 women protested against the mercury and cyanide contamination of the local river caused by gold mining. The march resulted in the Colombian government’s agreement to stem this harmful activity.

Initiatives in Mexico also provide great examples of how organized female activism can generate real impacts when it comes to the fight for human and environmental rights. Female-led organizations such as Fondo Semillas actively emphasize Indigenous women’s participation in defense of their culture and land. In partnership with Fondo Semillas, the National Network of Indigenous Women Weaving Rights for Mother Earth and Territory (RENAMITT) works on providing agrarian certificates to Indigenous women, allowing them to be acknowledged as owners of their land.

Earth Observation Technology: How Can Images Support Women in Activism?

Although the economic, social, and cultural impacts of expropriation for mining activities are clear within Indigenous communities, the extent of the territorial damage it causes is not always explicit. The difficulty civil society faces in spatially quantifying the extension of mining projects while on the ground makes knowledge of the full scope of expropriation (in real-time) inaccessible to affected communities.

Earth Observation (EO) now allows for the visualization of information on how the Earth’s physical, chemical, and biological systems are changing due to human activity. This is done through remote sensing technologies, such as satellites and radar. The images (visual data) provided by these technologies have been critical in understanding how large-scale extractivist projects impact Indigenous people’s livelihoods and the environment. One example is the use of EO (from Google Earth) satellite images in the Amazon Rainforest, which allow researchers to map out deforestation patterns in near-real-time and inform the Brazilian government of these illegal activities.

Digital cartography not only provides rich data, but could also evoke vivid emotions linked to places and situations, therefore making these phenomena more relatable. Moreover, access to satellite images can inform the impacted communities of the kinds of extractive activities being carried out, where they are located, and what damage they are causing to the land. However, for these images to be accurately representative, they must be adapted to Indigenous territory labels and borders that reflect the lands that local communities are familiar with. Google Maps and Earth currently offer search tools to visualize Indigenous territories in Brazil, based on the names of ethnic groups living within them. The replication of this tool to other regions could make EO more accessible to other Indigenous communities and activists across Latin America.

Female activists (who are at the forefront of the fight against land expropriation) would also benefit greatly from the use of EO tools for their advocacy, as data can both provide proof for their claims of expropriation and also be shared with other community members in an effort to gauge support for the cause. Because mining corporations have used misinformation as a strategy to prevent the participation and negotiation with the affected communities, images could work as a potent (and more easily understood) source of data to visualize the extent of the sector’s harmful actions. This could also help counter the inaccessible technical language used by corporations when communicating with communities, which often hinders their participation in decision-making.

However, access to geospatial monitoring technologies is still a challenge for rural populations. When it comes to women, this difficulty increases considerably. Studies show that mobile apps and digital platforms are less familiar to women than men (commonly due to traditional gender roles and inequitable access to resources, including technology). This represents a clear barrier for female activists to utilize technological tools for environmental and human rights advocacy. Although access to satellite imagery is currently facilitated by Google Maps and Earth, internet and mobile devices are still not widely available in most rural communities.

Steps Forward

Digital exclusion of women is a stark reality in Latin America, especially for rural women. According to the Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación Para La Agricultura (IICA,2020), in over half of Latin America and Caribbean countries women have less access to mobile phones than men, while lower-educated women living in rural areas account for “the least connected group”. As pointed out by the director of IICA, Manuel Montero this is “[…] yet another issue faced by rural women, who must overcome greater obstacles to secure funding, receive training, access formal employment opportunities, and own land.” Adding to that, feminist geographers have pointed out that the creation and handling of technologies, such as EO, are shaped by the existing power relations that favor men, as they are widely used for surveillance, warfare and management of resources. However, with women as an ever-growing presence in the fields of geography, technology, and quantitative research, this reality may be rapidly changing.

In order for female environmental and human rights activism to successfully utilize Earth Observation for advocacy, access to mobile phones and the internet should first be enhanced. According to OECD (2018) “access affordability, lack of education, as well as inherent biases and socio-cultural norms, curtail women and girls’ ability to benefit from the opportunities offered by the digital transformation”. Therefore, more effort needs to be made to not only ensure women’s participation in the digital world, but allow this participation to be transformative against gender and cultural biases.

About the author: Ana Deborah Lana is a Research and Content Intern at Data-Pop Alliance. She is Mexican/Brazilian, and holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Belo Horizonte in Brazil.

References

- Amnistía Internacional – AI (España). (2016). Perú debe proteger a Máxima Acuña de los ataques de la policía. Acciones. Available at: https://www.es.amnesty.org/actua/acciones/peru-maxima-acuna-dic16/

- Amnistía Internacional – AI (España). (2017). Las autoridades peruanas ponen punto final a la criminalización de la defensora Máxima Acuña. Artículo. Available at: https://www.es.amnesty.org/en-que-estamos/noticias/noticia/articulo/las-autoridades-peruanas-ponen-punto-final-a-la-criminalizacion-de-la-defensora-maxima-acuna/

- Assembly, U. G. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. UN Wash, 12, 1-18. Available at https://waubrafoundation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/United-Nations-Declaration-on-the-Rights-of-Indigenous-Peoples.pdf

- Barcia, I. (2017). Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractive Industries: An Overview of Critical Risks and Human Rights Obligations. Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition – WHRDIC, Association for Women’s Rights in Development – AWID. Available at: https://www.awid.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/whrds-confronting_extractive_industries_report-eng.pdf

- Brasil. (1996). Decreto No 1.775 de 8 de Janeiro de 1996. Presidência da República. Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. Available at: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/d1775.htm

- Carrere, M. Roma, V. (May 24, 2021) Demandados por proteger su territorio en 4 países de Latinoámerica. Mongabay https://es.mongabay.com/2021/05/mordaza-legal-al-menos-156-defensores-ambientales-demandados-por-proteger-su-territorio/

- Colectivo de Coordinación de Acciones Socioambientales – CASA. (2016). Guía práctica para identificar la violencia medioambiental contra las mujeres. Available at: https://www.ocmal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/guia_para_identificar_la_violencia_medioambiental_contra_las_

mujeres.pdf - Colombia. (2015). Constitución Política de Colombia: Actualizada con los Actos Legislativos a 2015. Edición especial preparada por la Corte Constitucional. Available at https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/inicio/Constitucion%20politica%20de%20Colombia%20-%202015.pdf

- Environmental Justice Atlas – EJAtlas. (2021). Hudbey Minerals Lawsuits: Nickel mining Fenix Project, Guatemala. Available at: https://ejatlas.org/print/duplicate-do-not-approve-hudbay-minerals-lawsuits-re-nickel-mining-fenix-project-guatemala

- Ervin, J. (2018). In defense of nature: women at the forefront. United Nations Development Programme – UNDP. Blog post. Available at: https://www.undp.org/blog/defense-nature-women-forefront

- Fondo Semillas. (2021). Fondo Semillas: Mujeres Sembrando Igualdad. Programas: Tierra. Available at: https://semillas.org.mx/tierra/

- Global Witness (2020). Last Line of Defence: The industries causing the climate crisis and attacks against land and environmental defenders. Annual Report. Available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/land-and-environmental-defenders-annual-report-archive/

- Hurt, S. R. (2020, May 27). Washington Consensus. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Washington-consensus

- Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura – IICA. (2020). Digital exclusion: an obstacle that hinders rural women’s work. Blog post. Available at: https://blog.iica.int/en/blog/digital-exclusion-obstacle-hinders-rural-womens-work

- Instituto Humanitas Unisinos. (2019). Ativista de causas ambientais é brutalmente torturada e assassinada em Nova Viçosa (BA). ADITAL. Available at: https://www.ihu.unisinos.br/78-noticias/586595-ativista-de-causas-ambientais-e-brutalmente-torturada-e-assassinada-em-nova-vicosa-ba

- Mexico. (2021). Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Constitución publicada en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 5 de febrero de 1917. Actualizada con reforma publicada DOF 28 de mayo de 2021. Available at: http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf_mov/Constitucion_Politica.pdf

- Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina (2021). Consultas sobre míneria https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/consulta/index

- Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina (2021). Proyectos mineros https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/proyecto

- Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina (2021) Conflictos mineros en Amércia Latina https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/conflicto

- Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina (2021) Conflictos por el agua https://mapa.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db-v2/agua/index

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – OECD. (2018). Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. Report. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf

- Oxfam Australia (2021). The gendered impacts of mining. Economic Inequality. Mining. Available at: https://www.oxfam.org.au/what-we-do/economic-inequality/mining/the-gendered-impacts-of-mining/

- Peru. (1993). Constitución Política del Perú. Available at http://www.pcm.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Constitucion-Pol%C3%ADtica-del-Peru-1993.pdf

- Ray Harris (2013) Reflections on the value of ethics in relation to Earth observation, International Journal of Remote Sensing, 34:4, 1207-1219, Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2012.718466

- Rojas, N. (2019). Afro Colombian Activist Francia Márquez Mina Survives Attack. The North Star. Available at: https://www.thenorthstar.com/p/afro-colombian-activist-francia-marquez-mina-survives-attack

- Scarpellini, A. (2021). How photos can curb illegal deforestation in the Amazon. The Keyword. Google Blogs: Nonprofits. Available at: https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/nonprofits/how-photos-can-curb-illegal-deforestation-amazon/

- Seamster, R. (2017). Creating maps that reflect indigenous geography. The Keynote. Google Blogs: Google Earth. Available at: https://blog.google/products/maps/creating-maps-reflect-indigenous-geography/

- Valencia, R. (2019). Francia Márquez, Renowned Afro-Colombian Activist: What Environmental Racism Means To Me. Earth Justice. Available at: https://earthjustice.org/blog/2019-august/francia-m-rquez-renowned-afro-colombian-activist-what-environmental-racism-means-to-me

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)