Just three weeks after the social distance measure was announced in Mexico, domestic violence related calls to the 911 emergency number increased by 60% and the federal authorities estimated that violence against women had gone up between 30% to 100% (Ortiz-b, 2020), an alarming prospect. The way in which government institutions and organizations act and react to the issue will matter not only now, but in the long-term.

Photo by Melanie Wasser on Unsplash.

Author: Berenice Fernández Nieto. Editors: Ivette Yáñez Soria, María Antonia Bravo.

“Peace is not just the absence of war. Many women under lockdown for COVID19 face violence where they should be safest: in their own homes”, United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, stated with regards to the severe consequences that COVID-19 confinement is inflicting on millions of women around the world (UN news, 2020). According to WHO data from 2016, globally, 1 in 3 women have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) and/or sexual violence, leaving damaging and long-lasting effects on women’s physical and mental health (WHO, n.d.).

In Latin America, a region that in spite of recent progress remains the most unequal in the world, violence against women (VAW) continues to raise at alarming levels, posing a constant threat to women across the region. In Mexico, a country with over 120 million people, the current Covid-19 pandemic will transversally impact a series of social issues, of which gender based violence is one of the most salient concerns (expected to grow by 92% during the quarantine period (Nava, 2020)). Evaluating the risks posed by a potential increase in gender based violence, particularly the ones faced by women spending long periods of isolation and lockdown alongside their aggressors, becomes a matter of urgency. Similarly, it is of great importance to assess the measures implemented by the federal government to combat this problem to determine the extent to which these measures are effective in protecting women and avoiding gender based violence.

The COVID-19 emergency is deepening existing gender gaps and inequalities and heightening the risk of violence for millions of women in Mexico. This article addresses the limitations of the framework put in place to ensure the safety of victims, the role of data and potential actions/recommendations to protect the rights of women throughout this crisis.

Violence against Women in Latin America

Latin America is considered the most violent region for women worldwide; this is largely due to the prevailing patriarchal culture, which governs all customs and practices of daily life leading to the naturalization of violence against women, the production of stereotypes, and the perpetuation and reproduction of discrimination (Moreno y Pardo, 2018). According to a gender violence study from 2016, the region holds 14 of the 25 countries with the highest rates of femicides (Small arms survey, 2016).

Emotional abuse, such as insults, humiliation, intimidation, and threats of harm, is also widespread in the Latin American countries. In fact, large proportions of women have reported that their current or most recent partner used three or more controlling behaviors, including attempting to isolate them from friends and/or friends, insisting on knowing their whereabouts at all times, or limiting their contact with friends or family (Bott, et al. 2012).

The data, though still limited, shows the urgency in visibilizing –what many are calling– the “shadow” epidemic, and examining the dimensions that domestic violence can take in the context of confinement by COVID-19. In order to do so, it is essential to collect and analyse appropriate data that allows authorities and organizations to make evidence-based decisions and effectively target at-risk populations.

Domestic violence in Mexico

In Mexico, many of the violent deaths of women are femicides –killings in which victims are targeted in relation to the social conditions of their gender. This figure is alarmingly increasing: From seven violent assassinations of women per day just two years ago, this figure has gone up to 10 killings per day this year according to the Mexico office of UN Women (Villegas and Malkin, 2019). This scenario only speaks to the most heinous expressions of gender violence. However, more dimensions of this phenomenon are present across the country (e.g. work-based and educational, community-based, and institutional violence), amongst which domestic violence is particularly worrisome.

An INEGI (Mexico’s National Statistical Office) survey from 2016 revealed that seven out of every 10 women have experienced violence at some point in their lives, and of those, almost half (43.9%) were abused by their husband, boyfriend, or partner (El Universal, 2019). This category encompasses victims of physical and/or sexual violence taking place from time to time, along with victims of severe physical and emotional damage, such as cuts, burns, lost teeth, hemorrhages, nervous breakdowns, anguish, fear, sadness, affliction, depression or insomnia (Migueles, 2018).

The states with the highest levels of domestic violence are (out of 32): the State of Mexico, Mexico City, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, and Queretaro, with a total of 12 states above the national average, which is at 66% prevalence according to the Relation’s Dynamic at Home National Survey, 2016) (Migueles, 2018).

Legal framework

At the international and regional level, Mexico is part of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (1979); the Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention of Belem do Para) (1994); the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995), and the InterAmerican Commission of Women.

At the national level, the legal framework states the need for the eradication of all forms of violence against women, which is outlined within the General Law on Women’s Access to a Life Free of Violence (LGAMVLV) (2007); the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence Against Women’s (2009) Comprehensive Program to Prevent, Address, Punish and Eradicate Violence against Women 2014- 2018 (INEGI, 2020).

Despite the existence of a framework, the current pandemic, as it is discussed below, has shown the weakness of the system in procuring the safety of women.

Network of shelters

In Mexico, one of most important tools for enacting the protection of women against violence is the Network of Shelters for victims of domestic violence. The goals of these centers include promoting political advocacy to end VAW and providing capacity-building for the professionals who work in these spaces. The shelter locations are kept confidential to avoid potential aggressions or endangerment of the women, as well as to promote their autonomy within a culture of proper treatment. Women can stay in these centers for up to three months (Mancera, 2015).

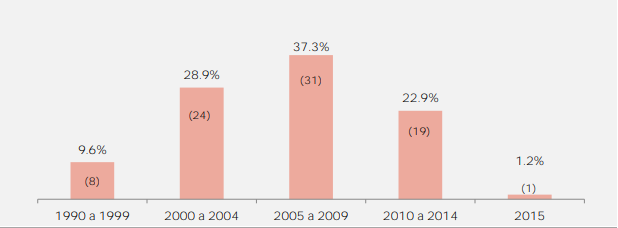

The existence of refuges in Mexico dates back to the 90s. These spaces emerged as an initiative of the organized civil society, and as an achievement of women’s movements who were able to place the topic at the heart of the public agenda. The first shelters opened in 1996 (less than 30 years ago), and eight more shelters began activities between 1996 and 1999. This number tripled between 2000 and 2004, and in the period 2005-2009, the most significant number of shelters (31) were functioning (InMujeres, 2016). In 2015, the Social Assistance Housing Census reported that 83 shelters were operational throughout the country.

In terms of internal regulation, the National Institute for Women (Inmujeres) collaborates with the National System to Prevent, Address, Punish and Eradicate Violence against Women (SNPASEVM) to design and evaluate the model of care for victims. Together, they established guidelines regarding the homologation of the basic conditions in which a refuge must operate, and seek to standardize services (InMujeres, 2016).

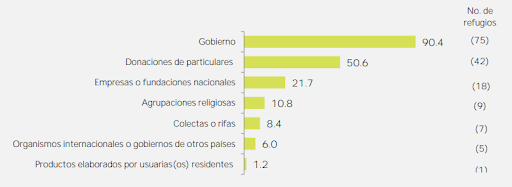

Shelters have various sources of financial support: the government has an essential participation in granting public resources, covering 75 of the 83 centers. At the same time, 50.6% receive private donations and 8.4% carry out fundraising activities to access more resources (see graph 2) (InMujeres, 2016).

Domestic violence in Mexico during COVID 19 quarantine

When the Healthy Distance Initiative (Jornada Nacional de Sana Distancia) was launched, civil organizations declared that measures must be put in place to guarantee women’s access to a life free of violence during the health crisis and to ensure that policies to combat gender violence were not neglected as a result of shifting priorities. In particular, International Amnesty, Red Nacional de Refugios (RNR – Network of Shelters for victims of domestic violence), and Equis Justicia para las Mujeres highlighted the necessity to i) deliver public resources to the shelters; ii) guarantee the functioning of justice centers, and iii) ensure justice delivery services for this sector of the population (Ortíz, 2020).

However, prior to the beginning of the social distance measures, the 911 emergency number registered 21,727 VAW related calls for the month of February (Galván, 2020), and just three weeks the measure was announced, federal authorities estimated that VAW had increased between 30% to 100% (Ortiz-b, 2020), an alarming prospect.

Within this context, domestic violence demonstrated to be one of the most concerning matters. Almost two months after the registration of the first COVID-19 case in Mexico, the Shelter Network observed an increase of 5% in women’s admissions and 60% in guidance via telephone, social networks, or email. Additionally, centers linked to the RNR are at 80% or 110% of their capacity, especially in entities such as Guanajuato, the State of Mexico, and Chiapas (Castellanos, 2020).

A gender perspective for the national strategy to combat COVID-19

The previous numbers indicate that adopting a gender perspective within the pandemic policy strategy is essential, especially if we account for the government estimation that two-thirds of the female population in the country over the age of 15 will quarantine alongside a violent partner (De la Peña, 2020).

Moreover, experts have pointed out that the COVID pandemic and its containment measures will impact men and women unevenly, the latter being the main ones to be employed in industries with little protection, low wages, long working hours and few social benefits, and, as mentioned earlier, being the first in the line of exposure to contagion as workers in the health field.

UN WOMEN has made specific recommendations to the authorities whose objective is to help alleviate the adverse conditions that women will suffer throughout the confinement (UNWomen, 2020). At this stage of the pandemic, the international organization suggest that the government guides companies and work centers on:

- Raising awareness of the increased burden on female staff for extra care tasks against COVID 19.

- Helping employers take into account the risks that their employees displacement will have, as well as ensuring their payments during the quarantine.

- Protecting the workforce in manufacturing companies (maquiladoras) economically and through labour. protection measures since women make up a large part of the workforce.

- Procuring strategies to protect those affected by the sexual division of labor in areas such as education, social work, which are mostly composed of women.

- Providing especial attention for older women living alone (UNWomen, 2020).

It is therefore crucial that the plans of the Mexican government to fight COVID-19 incorporate a gender perspective based on the fact that every action taken (or non-taken) will affect the lives of women and girls both now and, undoubtedly, in the long-term (Cimac, 2020).

Initiatives: “No estás sola, seguimos contigo” and “#ContingenciaSinViolencia”

On April 7th, the Mexican government presented the “No estás sola, seguimos contigo [You’re not alone, we are still with you]” program, in coordination with the Citizens Council (Consejo Ciudadano) and the Women’s Secretariat (Secretaria de las Mujeres) to deal with complaints of family violence during the quarantine period (Almazán, 2020). The program consists of several actions seeking to facilitate reporting through the number 55 5533-5533 and support. These actions are:

- Trusted chat, in which it is possible to share video, photos and text discreetly.

- Assistance via videoconference.

- Channeling to the Lunas centers (which provide psychological and legal care) for medium and high-risk cases, as well as to the 24 agencies with the service of female lawyers.

- Collaboration with the Women Line through 5658-1111, which will provide citizen’s support, in addition to having 89 psychologists and 130 lawyers (Almazán, 2020).

Additionally, the federal government and the National Commission to Prevent and Eradicate Violence against Women (Conavim) created a directory to publicize Justice Centers for Women at the national level.

The hashtag #Contingencywithoutviolence (in Spanish “ContingenciaSinViolencia”) has spread on social networks and, taking advantage of the online movement, a campaign with the same name was launched by the State of Mexico. Possibly a relevant strategy as this state concentrates the highest number in gender-based violence cases at the national level (Velasco, 2020) (Fuentes, 2019).

Shelters needs during the quarantine

Of course, a fundamental element to face the contingency from a gender perspective is the optimal functioning of the shelter network. Yet, at this moment (April 2020), the National Network of Shelters (RNR) lacks a budget and space to operate, meaning they are dealing with a double or triple contingency. In order to handle the situation, civil society members and journalists have demanded to shorten the usual federal period of 30 business days to allocate a budget for these centers (Aristegui, 2020).

“Rights are not consulted, are not negotiated, they are exercised,” said Wendy Figueroa, National Shelter Network director. Several organizations pointed out that the delay in the allocation of financial resources violates the shelters’ operation and rights of women to safety. As a result, they have urged the federal government to establish a budget, as well as evaluation and monitoring mechanisms that guarantee the permanent flow of resources allowing the shelters to work throughout the year without any impediment. Figueroa also pointed out that if the contingency period were to be extended to May (which it has), the shelters would be covering the entire contingency period without budget to do so (Aristegui, 2020).

In this panorama, it must be recognized that Mexico is facing a double contingency that involves a gender and health crises, and both demand the highest level of attention. Up until April 21, 100 women have died since the virus broke into the country on February 28, while 367 have been killed in roughly the same period (Global Health 5050, 2020; Castellanos, 2020).

The role of data

In general, today more than ever, data analysis is necessary to contain the pandemic and identify the population with the highest risk. Researchers and developers around the world have been analyzing large amounts of data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the disease. Mobile data, for example, has shown its potential in predicting the spatial spread of cholera during the 2010 Haiti cholera epidemic, while leveraging big-data analytics showed effectiveness during the 2014–2016 Western African Ebola crisis (Ienca and Vayena, 2020).

In this regard, several big-name organizations (Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, etc.) have launched projects to contribute in reducing the impacts of the pandemic, while others have recently offered researchers free access to open datasets and analytics tools that should help them develop COVID-19 solutions more quickly (Kent, 2020). Yet, more work needs to be done, and it is essential to include a gender approach into data analysis projects, especially in view of the intensification of gender gaps as a consequence of the crisis.

UN Women issued a series of recommendations that place women’s needs and leadership at the center of effective responses against COVID-19. One of them is to ensure the availability of sex-disaggregated data, including differentiated infection rates, differentiated economic impacts and burden of care, and incidence of domestic and sexual violence (UN Women, 2020). In this sense, the data becomes an important ally in the containment of COVID-19, as it makes visible the diverse effects of the pandemic for men and women.

Another valuable information source during this pandemic is data extracted from social media, which can potentially shed light on how people are bearing the burdens and stresses of the pandemic, and how it is disproportionately affecting men and women of all ages and with different vulnerabilities, as it could be disability or educational barriers. More advanced applications may consist of correlating environmental or genetic factors to the people presenting advanced respiratory problems (Kent, 2020).

Conclusions and recommendations

It is clear that in addition to the exacerbated challenges that the COVID-19 epidemic represents to Mexico, the effects of another long-standing epidemic are added: gender based violence, and specifically, domestic violence. So far, gender based violence has claimed more women’s lives than the number of female victims for COVID-19 in this country (since February 28, when the first COVID case was registered, up to April 21), and the implications of a prolonged lock down are already widening gender gap inequalities and increasing violence against women. Therefore, government authorities must strengthen all mechanisms for addressing these issues at national and local levels, which translates in several actions ranging from the continuous operation of justice institutions, to the appropriate financing of shelters for female victims of abuse.

The normalization of gender based violence and other gender related inequalities is unfortunately, already a normalized phenomenon., If we are to avoid making the gender problematic invisible in the face of a pandemic whose scale has no precedent in modern history, bold and strategic steps have to be taken immediately. We propose the following recommendations.

- The centers of attention to victims, as well as the emergency numbers, must ensure their continuous operation and the quick and effective response to women who suffer domestic violence. Wendy Figueroa, National Shelter Network director, has suggested that the 911 line must be linked directly and with geolocation so that at any time, when a person denounces a situation of violence, the authorities have the exact location and ensure that no time is wasted in the response process.

- It is necessary to move to a model of victims’ attention that focuses on the protection and safety of those at risk. Avoiding at all costs replicating what we know as the “route of (in) justice” in which women, girls, adolescents, and older adults travel an average of 5 institutions before finding comprehensive services (Pérez, 2020).

- Resources must be properly targeted to women at risk: indigenous women, elderly women living alone, single mothers, women with occupational disabling illnesses, women with low incomes and no health insurance, etc., who are the most vulnerable in this double contingency. (Galván, 2020)

- Health personnel must have the necessary equipment to carry out their work so that their work does not represent a risk to their health or the health of their family.

- Having data disaggregated by gender would be an invaluable element in targeting economic, social, and health assistance programs to combat the crisis generated by COVID-19. Similarly, the alliance and cooperation between government authorities, in terms of access to health data and other social indicators, would boost the work of hundreds of scientists and associations that work every day to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic is posing, exposing and exacerbating challenges for countries and communities across the Global South that will have global long term repercussions. Responding to the various impacts and implications of this crisis calls for bold thinking and forceful actions. Learn more about our contribution here.

References

Almazán, Jorge. (2020). ‘CdMx lanza programa contra violencia familiar durante cuarentena por covid-19”. Milenio. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.milenio.com/politica/comunidad/co vid-19-cdmx-lanza-programa-denunciar-violencia-familiar> (Consulted: 15/04/2020)

Aristegui Noticias. (2020). “Viven refugios para mujeres doble crisis en pandemia”. [Online]. Available at: <https://aristeguinoticias.com/1404/mexico/viven-refugios-para-mujeres-doble-cr isis-en-pandemia/> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Bott, Sarah; Alessandra Guedes; Mary Goodwin, and Jennifer Adams Mendoza. (2012). “Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries.” Pan American Health Organization; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdo cuments/2014/Violence1.24-WEB-25-febrero-2014.pdf> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Castellanos, Laura. (2020). “México abandona a las mujeres violentadas en esta contingencia”. Aristegui Noticias. [Online]. Available at: <https://aristeguinoticias.com/1404/mexico/mexic o-abandona-a-las-mujeres-violentadas-en-esta-contingencia-articulo/> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Cimac. (2020). “Sin política de género ante COVID-19, se profundiza desigualdad de género: analistas”. [Online]. Available at: <https://cimacnoticias.com.mx/2020/03/25/sin-politica-de-gen ero-ante-covid-19-se-profundiza-desigualdad-de-genero-analistas> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

De la Peña, Angélica. (2020). “El Covid-19 y la perspectiva de género”. El Sol de México. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.elsoldemexico.com.mx/analisis/el-covid-19-y-la-perspe ctiva-de-genero-5004905.html> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

El Universal. (2019). “Domestic violence has been normalized in Mexico”. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/domestic-violence-has-been-normalized-mexico> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Fuentes, Mario Luis. (2020). “Concentran 5 estados asesinatos de mujeres; violencia de género”. Excelsior. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/concentran- 5-estados-asesinatos-de-mujeres-violencia-de-genero/1349712> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Galván, Melissa. (2020). “Otra contingencia: la violencia contra las mujeres va en aumento”. Expansión política. [Online]. Available at: <https://politica.expansion.mx/mexico/2020/04/05/ot ra-contingencia-la-violencia-contra-las-mujeres-va-en-aumento> (Consulted: 15/04/2020)

Global Health 5050. (2020). “COVID-19 sex-disaggregated data tracker”. [Online]. Available at: (Consulted: 15/04/2020)

Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. (INEGI). (2020). “Measuring violence against women in Mexico”. [Online]. Available at: <https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/Events/20%20O ct%202015/Mexico.pdf> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Ienca, Marcello & Effy Vayena. (2020). “On the responsible use of digital data to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic”. Nature. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591- 020-0832-5> (Consulted: 17/04/2020)

Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. (2016). Relation’s Dynamic at Home National Survey, 2016). [Online]. Available at: <https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/endir eh/2016/doc/endireh2016_presentacion_ejecutiva.pdf> (Consulted: 15/04/2020)

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres. (InMujeres). (2020). “¿Sufres violencia? ¿Temes que tu situación se agrave ante el confinamiento por el Covid-19? No estás sola”. Gobierno de México. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.gob.mx/inmujeres/articulos/servicios-de-atencio n-a-mujeres-en-situacion-de-violencia-de-los-estados?idiom=es> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres. (InMujeres). (2016). “Refugios para mujeres, sus hijas e hijos en situación de violencia: un diagnóstico a partir de los datos del Censo de Alojamientos de Asistencia Social, 2015”. Gobierno de la República. [Online]. Available at: <http://cedoc.inmujeres.gob.mx/documentos_download/101267.pdf> (Consulted: 15/04/2020)

Justicia y Derechos Humanos. (2020). “Si durante este periodo de contingencia por #Covid_19mx sufres de algún tipo de agresión en tu hogar, no lo dudes y llama a la línea sin violencia: 800 108 40 53. #ContingenciaSinViolencia”. [Tweet]. Available at: <https://twitter.com/SJyDH_Edomex/status/1246514788122976259> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Kent, Jessica. (2020). “Understanding the COVID-19 Pandemic as a Big Data Analytics Issue”. Xtelligent Healthcare Media. [Online]. Available at: <https://healthitanalytics.com/news/understa nding-the-covid-19-pandemic-as-a-big-data-analytics-issue> (Consulted: 17/04/2020)

Mancera, Katherine. (2015). “In Mexico, a Network of Shelters Gives Women Agency and Hope”. Hispanics in Philanthropy. [Online]. Available at: <https://hiponline.org/in-mexico-a-ne twork-of-shelters-gives-women-agency-and-hope/> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Migueles, Rubén. (2018). “Millions of women are victims of domestic violence”. El Universal. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/english/women-domestic-violence/> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Moreno, Rebeca y Laura Pardo. (2018). “La violencia contra las mujeres en Latinoamérica”. Foreign Affairs Latinoamérica. [Online]. Available at: <http://revistafal.com/la-violencia-co ntra-las-mujeres-en-latinoamerica/> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Nava, Cecilia (2020). ¨En cuarentena, violencia contra la mujer escalará 92%, prevén expertas¨. El Sol del México. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.elsoldemexico.com.mx/metropoli/cd mx/en-cuarentena-violencia-contra-la-mujer-escalara-92-preven-expertas-coronavirus-covid-19-5022583.html> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Ortiz, Alexis. (2020). “Urgen prevenir la violencia de género durante la cuarentena por Covid-19”. El Universal. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/corona virus-urgen-prevenir-violencia-de-genero-durante-cuarentena-por-covid-19> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Ortiz, Alexis (2020). “Estiman aumento de hasta 100% en violencia de género por confinamiento ante coronavirus”. El Universal. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.eluniversal .com.mx/nacion/coronavirus-en-mexico-estiman-aumento-de-hasta-100-en-violencia-de-genero> (Consulted: 20/04/2020)

Peres de Oliveira, Selma Maria da Fonseca Viegas; Walquíria Jesusmara dos Santos; Edilene Aparecida Araújo da Silveira, and Sandra Cristina Elias. (2019). “Women victims of domestic violence: a phenomenological approach”. Texto contexto – enferm. vol.24 no.1 [Online]. Available at: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-07072015000100 196> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Pérez, Maritza. (2020). “Violencia intrafamiliar aumenta hasta 100% por cuarentena”. El Economista. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/politica/Violencia-intra familiar-aumenta-hasta-100-por-cuarentena-20200409-0020.html> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Sattarzadeh, Niloufar; Azizeh Farshbaf-Khalili, and Tayebeh Hatamian-Maleki. (2019). ¨An Evidence-Based Glance at Domestic Violence Phenomenon in Early Marriages: A Narrative Review¨. International Journal of Women’s Health and Reproduction Sciences Vol. 7, No. 3. [Online]. Available at: <http://ijwhr.net/pdf/pdf_IJWHR_375.pdf> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Small Arms Survey. (2016). “A Gendered Analysis of Violent Deaths”. Research Notes. [Online]. Available at: <http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/H-Research_Notes/SAS-Research- Note-63.pdf> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

UN News. (2020). ¨UN chief calls for domestic violence ‘ceasefire’ amid ‘horrifying global surge’¨. [Online]. Available at: <https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061052> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

UNWomen. (2020). “Atender las necesidades y el liderazgo de las mujeres fortalecerá la respuesta ante el COVID-19”. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.unwomen.org/es/news/storie s/2020/3/news-womens-needs-and-leadership-in-covid-19-response> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Valera, Eve. (2018). “Intimate partner violence and traumatic brain injury: An ‘invisible’ public health epidemic”. Harvard Health Blog. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.health.harvard.e du/blog/intimate-partner-violence-and-traumatic-brain-injury-an-invisible-public-health-epidemic-2018121315529> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

Velasco, Ángeles. (2020). “Edomex busca evitar violencia intrafamiliar por confinamiento”. Excelsior. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/edomex-busca-evi tar-violencia-intrafamiliar-por-confinamiento/1373987> (Consulted: 16/04/2020)

Villegas, Paulina and Elisabeth Malkin. (2019). “‘Not My Fault’: Women in Mexico Fight Back Against Violence”. The New York Times. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/20 19/12/26/world/americas/mexico-women-domestic-violence-femicide.html> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

World Health Organization (WHO). (n.d.). ¨Implementing the WHO clinical and policy guidelines for responding to violence against women in countries¨. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/violence/vaw/en/> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). ¨Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women¨. [Online]. Available at: <https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/pub lications/violence/9789241548595/en/> (Consulted: 01/04/2020)

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)