GENDER DATA SERIES

This is the fourth edition of Data-Pop Alliance’s “Gender Data Series”, which comprises interviews, videos, and opinion articles with gender data experts from around the globe to bring light to issues at the intersection of gender and data, such as health, migration, livelihoods and, of course, gender-based violence (GBV).

Transportation policies and infrastructure tend to favour mobility over accessibility (Roy, 2009). Women all over the globe have to cope with male-designed urban planning, especially those in the Global South and women from ethnic, social, or sexual minorities, who already face more vulnerability in public spaces. The first problem when addressing women’s access to the city’s facilities arises from the lack of sex-disaggregated data for mobility. Without quality data that sheds insights into who and for which purpose public transportation is being used, it is hard to design public policies focused on the user’s needs, which is especially true for women. This is particularly troubling given that the available data suggests that women use public transportation more than men, and also experience the most hardship. How can it be then that approximately 50% of the population use public transportation designed for men and their needs?

Barriers Affecting Women's Travel

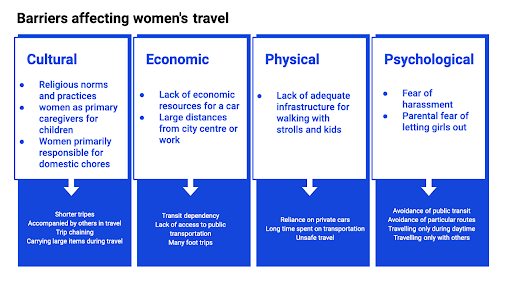

Women face several barriers when using public transportation. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris (2020) divides the barriers into four categories: cultural, economic, physical, and psychological. The first category, cultural barriers, includes religious norms and pre-defined social roles. The fact that women are more often responsible for domestic chores and child-caring is reflected in their travel patterns. Women usually make shorter trips, are accompanied by others, and carry larger items and bags than men.

The second type of barriers are economic, which most directly impacts poor women in the Global South. For example, when a family only owns one car, men are more likely to use it for work, even if both spouses are employed (European Commission, 2014). It must be noted that significantly fewer women than men in the Global South own cars or have a driver’s licence (Rosenbloom and Plessis-Fraissard, 2009). In general, women are more dependent on public transportation than men and — and when they lack resources to pay for public transportation— are forced to walk instead.

The third category is physical barriers. Cities have predominantly been designed around men’s necessities, habits, routines and bodies, hence leading to a lack of adequate infrastructure for women. Sidewalks that are too narrow, or metro systems without stairs, are not only inaccessible to people with disabilities, but also for women carrying strollers. Additionally, the majority of metro stations around the world lack designated areas for child-caring. Women are therefore often exposed to harassment when breastfeeding their children in the middle of the station. Moreover, few stations provide diaper changing areas for mothers, or public toilet facilities in the street or in stations.

The fourth category relates to psychological barriers, which arise from fear of harassment on public transportation, causing women to change, extend and even make their travel patterns more expensive. Specifically, they tend to avoid particular transit routes, and travel only during the daytime, or if accompanied by others. These barriers hamper women’s mobility, daily experiences and usage of public spaces, without mentioning their contribution to the reinforcement of gender inequality.

What is Causing the Lack of Data?

Collecting sex-disaggregated data on public transportation and mobility is incredibly simple. Annual surveys are conducted by governments and transportation companies in order to provide better services, but little attention is paid to the specific needs for women. If data is focused solely on nine to five commuters, people who work outside those standard office hours are excluded, including those in unpaid labour. Women, for example, tend to make short and frequent trips for household and care purposes, and those trips should also be documented and considered when measuring public transportation efficacy. However, is it also the case that survey designs are biassed towards a male perspective?

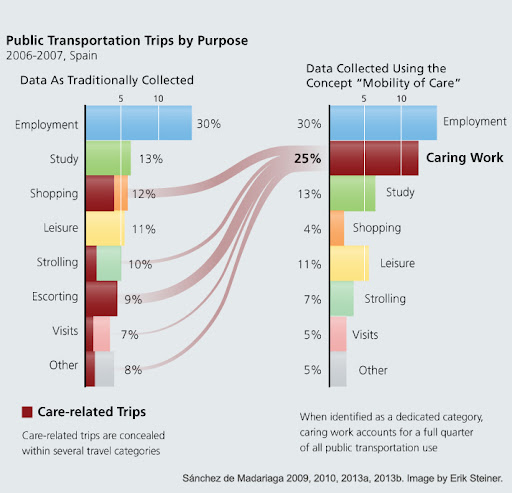

This graph, which illustrates a survey conducted in Spain, outlines how traditional approaches to data collection can misinterpret transportation uses and thus underreport the amount of caring work performed by women (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2009). This is a clear example of how better-designed surveys could be utilized for collecting sex-disaggregated data and changing transportation policies to positively impact different groups.

What Can We Conclude Based on the Available Data?

Available data shows that women use more public transportation than men. In France, two-thirds of public transport passengers are women; in Philadelphia and Chicago (US) the figure is 64% and 62% respectively (Ceccato, 2017). Despite this, female mobility restrictions begin at a young age as parents tend to give their sons greater freedom to move around city spaces than their daughters, who are perceived as more susceptible to the threat of ‘stranger danger’ (Loukaitou-Sideris and Sideris, 2010).

Data also tells us something about travel patterns. Men are most likely to have fairly simple travel patterns: a twice-daily commute in and out of town; meanwhile, women’s tend to be more complicated. Women do 75% of the world’s unpaid care work, which affects the way they move around the city (Perez, 2019). In London, for instance, female commuters are three times more likely than men to take children to school and 25% more likely to trip-chain (make one or more stops, e.g.: to do groceries, pick children from school); the latter figure rises to 39% when there is a child older than nine in the household (Transport for London, 2019).

Data on harassment on public transportation is scarce but sobering, with the main finding being that women do not feel safe using it. In Brazil, according to a survey conducted in 2014, two-thirds of women had been victims of sexual harassment while in transit, half of them while using public transportation (Ceccato and Paz, 2017). By contrast, the proportion among men was 18%. When asked if men ever whitnessed a sexual harassment case, the majority of them said no. In the UK, 62% of women are scared of walking in car parks, 60% feel afraid waiting on train platforms, 49% are scared waiting at the bus stop, and 59% feel unsafe walking home from a bus stop or station (Loukaitou-Sideris et al, 2009.). These numbers may well be conservative, as many women avoid reporting (for various reasons). In Washington DC, a 2016 survey found that 77% of those harassed in the metro never reported these incidents (Perez, 2019).

Besides the lack of data and public policies focused on women’s concerns, women also represent a minority in the transportation industry. A 2019 report from the Mineta Transportation Institute revealed women make up less than 15% of all transportation workers in the US. This imbalance makes it even harder for the transportation industry to enforce policies focusing on women’s needs.

"In London, for instance, female commuters are three times more likely than men to take children to school and 25% more likely to trip-chain (make one or more stops)."

Transport for London, 2019- Developer

Strategies Implemented To Close the Gender Mobility Gap

Based on the evidence, strategies have been implemented in several cities to make women feel safer using public transportation. The strategies are simple and mostly inexpensive to achieve. In London, for instance, transparent bus shelters were built for better visibility. Second, lightning was increased in several stops and metro stations. Third, some cities set up digital timetables, so women know when the next bus is coming, cutting down the time they must wait alone (Perez, 2019). These three are examples of how creative thinking and technology can help bridge the gender gap in urban spaces. Fourth, an efficient (yet uncommon) measure has been the introduction of request stops in between official stops for women travelling on night buses. Fifth, cities such as Tokyo, Rio de Janeiro, and Cairo introduced “women-only” carriages. In Mexico City, these carriages are only available during rush hours. However, the policy is not enforced in the majority of the cities or is limited to specific lines.

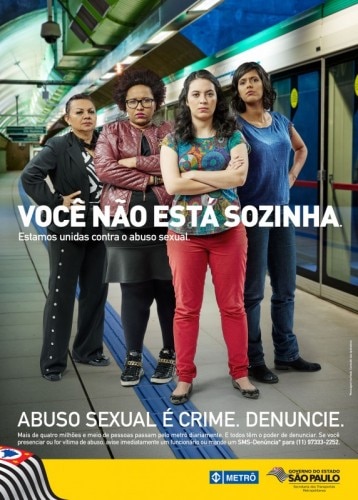

Another popular strategy is launching advertising campaigns to combat sexual harassment in the subway. In São Paulo, a campaign was successful in increasing the number of reported cases, but not in improving women’s safety (Soares, 2015).

What is Still Missing? Lack of Data and Public Initiatives

As stated above, public policies based on evidence are crucial to enhancing women’s experience on public transportation and their overall wellbeing and urban mobility. Evidence should stem first from sex-disaggregated data, which is still missing in the majority of public research, as surveys tend to focus on the average user experience, but not specifically on women’s concerns. Evidence of the need for public and private organisations’ action based on evidence is the fact that women have started collecting data themselves in order to make mobility safer for other women. One example comes from New Delhi, where an initiative to track hot spots of harassment was created. New Delhi is one of the most dangerous cities for women, where one rape is reported every 29 minutes. A 2013 survey found that 95% of women and girls living in the city do not feel safe from sexual violations in public spaces (Gaynar, 2013). One year after the “Delhi gang rape” incident, three women set up a crowd mapping platform named Safecity. Through this service women can report the location, date, and time they were harassed or attacked, as well as provide details so other women can be aware of areas and situations to avoid. The datahub reveals that groping is the most common type of harassment and public buses are the most dangerous form of public transportation for women, likely due to overcrowding (Gaynar, 2013).

The cultural, economic, physical, and psychological barriers women face while in transit can be tackled with policies based on sex-disaggregated data aimed at addressing women’s major concerns. Governments, municipalities, and the transportation industry, including private companies, should ensure that women’s concerns are heard, in order to provide a safer environment for women. Among these concerns are highlighted sexual harassment, undervalue of short trips, and trips with children and babies. Mobility policies are not only crucial for enhancing the quality of mobility itself: Women’s Mobility is an Important Step Towards Women’s Empowerment.

Author: Yara Antoniassi is a Brazilian Research and Content Intern at Data-Pop Alliance, currently studying at Erasmus University in the Netherlands.

References

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. and Sideris, A. (2010). ‘What brings children to the park? Analysis and measurement of the variables affecting children’s use and physical activity’, Journal of the American Planning Association, 76, 89–107.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Bornstein, A., Fink, C., Samuels, L., & Gerami, S. (2009). ‘How to ease women’s fear of transportation environments: Case studies and best practices’ [online]. CA: Mineta Transportation Institute.

- Mandhana, N., & Trivedi, A. (2012). ‘Indians outraged over rape on moving bus in New Delhi.’ The New York Times, 18.

- Perez, C. C. (2019). ‘Invisible women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men.’ Random House.

- Roy, A. (2009). ‘Gender, poverty, and transportation in the developing world’, in Women’s Issues in Transportation, Conference Proceedings 46, Volume 1, Washington, Transportation Research Board, 50–62.

- Rosenbloom, S. and Plessis-Fraissard, M. (2009). ‘Women’s travel in developed and developing countries: two versions of the same story?’, in Women’s Issues in Transportation, Conference Proceedings 46, Volume 1, Washington, Transportation Research Board, 63–77.

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2009). ‘Vivienda, Movilidad, y Urbanismo para la Igualdad en la Diversidad: Ciudades, Género, y Dependencia.’ Ciudad y Territorio Estudios Territoriales, XLI (161-162), 581-598.

- Soares, N.(2015). ‘Campanha do Metro de SP Contra Abuso Sexual Tem 79% de Aprovacao.’ http://emais.estadao.com.br/blogs/nana-soares/campanha-do-metro-de-sp-contra-abuso-sexual-tem-79- de-aprovacao/