For over 40 years, the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program “has shaped policies, informed research, and transformed lives” (Brookings, 2025). The termination of the Program in February 2025 raises serious concerns about the future of health—including sexual and reproductive health—and gender-based violence data in more than 25 countries where DHS will no longer be conducted.

This blog explores the Program’s vital contribution to development efforts across the Global South and reflects on the far-reaching consequences of the U.S. government’s decision to end it, underscoring the broader impact on global health research and policy implementation. It also highlights the essential role of data in shaping effective policies that address the needs of vulnerable populations and support gender equality as well as sustainable development worldwide.

A Brief Look into the DHS Program

The DHS Program was established in 1984 with funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), as a successor to the World Fertility Survey (WFS). It is a global initiative dedicated to the collection, analysis, and dissemination of high-quality, nationally representative, and open-source data on a wide range of topics, including childhood and maternal mortality, child health, nutrition, malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, anemia, and education. Questions on domestic violence were added in 1990, leading to a comprehensive approach on monitoring GBV.

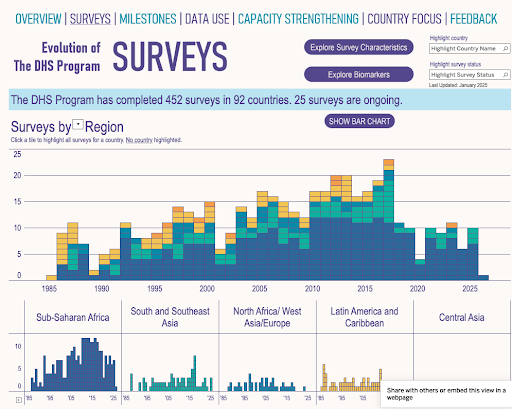

In its early years, the DHS Program covered only a limited number of countries. However, according to the DHS website, it has since expanded significantly, conducting over 400 surveys in more than 90 countries across Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe. The Program’s primary objective is to generate reliable data to inform evidence-based policymaking and guide program development, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where official statistics on key population and health indicators are often scarce or unavailable. In doing so, DHS plays a crucial role in addressing critical data gaps and strengthening the capacity of National Statistical Offices (NSOs) to produce and use demographic and health information effectively.

The DHS surveys are implemented by NSOs, with technical support from the DHS Program in the design, analysis, and implementation of survey instruments. As such, the Program also serves as a mechanism for institutional strengthening, enhancing local expertise in data collection, analysis, and utilization (Corsi et al., 2012).

Standardized questionnaires are utilized to ensure comprehensive and comparable data collection. These include the Household, Women’s, and Men’s Questionnaires, which gather information on demographics, reproductive health, and gender-related issues, as well as Biomarker Collection for assessing key health indicators through biological samples. They also gather information on critical topics such as child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), offering a more complete picture of gendered social norms and practices (Liang et al., 2021). While standardized, these tools are adapted to reflect the socioeconomic and cultural contexts of each participating country.

Thanks to consistent USAID funding, up until the termination of the program earlier this year, DHS data and reports are freely accessible online. Standardized formats enhance comparability across countries, and detailed survey documentation promotes transparency and external review (Fabic et al., 2012).

Why This Program Matters

First, because demography matters. Demography shapes economies, policies, and social structures. Population trends—such as birth rates, aging, and migration—directly impact labor markets, healthcare, urban development, and social inequalities. Governments and organizations rely on demographic data to plan for the future, allocate resources, and address pressing challenges like workforce shortages and public health crises (Goldstone, 2012; Ray, 2020).

Second, the DHS Program plays a crucial role in government operations. It provides high-quality data that informs a wide range of policy decisions, enabling policymakers to design targeted and data-driven interventions in healthcare, family planning, maternal and child health, and nutrition. By analyzing indicators such as fertility rates and child mortality, governments can prioritize healthcare initiatives and address disparities in service delivery. Additionally, DHS data supports more effective resource allocation—for example, identifying regions with high maternal mortality rates allows governments to direct resources and healthcare personnel where they are needed most.

For example, Tanzania’s health policy is shaped by data from consecutive DHS surveys. The Fifth Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP V) emphasizes household surveys as essential tools for tracking health progress. Key indicators include institutional birth rates (those occurring in a health facility), modern contraceptive use, and malaria prevalence in young children. Findings from the 2015/16 DHS and the Malaria Indicator Surveys (MIS) on child malnutrition contributed to the development of the National Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan (The Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2025).

The DHS also plays a vital role in monitoring and evaluating public health programs. By comparing new data with past surveys, governments can measure progress, identify weaknesses, and adjust policies accordingly. The data also supports international reporting, including tracking progress toward the SDGs, and informs policies in education, gender equality, and economic development (Corsi, 2012). Understanding population needs enables governments to improve services and reduce inequalities.

For researchers, the DHS is an invaluable resource, offering standardized and reliable data on health, fertility, mortality, nutrition, and gender issues across multiple countries. Its large sample sizes and consistent methodology allow for cross-country and long-term comparisons, helping to identify global and regional health challenges.

Additionally, the DHS provides insights into sensitive topics like maternal and child health, reproductive health, and gender-based violence—areas often difficult to study due to cultural barriers. By making its data publicly accessible, the DHS empowers researchers, policymakers, and organizations to conduct independent studies, develop evidence-based solutions, and improve public health strategies.

A study analyzing the use of DHS data in research from 1984 to 2010 found that it has been cited in over 1,100 publications across more than 200 journals. The number of publications has steadily increased since 1985, with an average annual rise of 4.3 papers. Of these, 51% focus on Population, Reproductive, and Health (PRH), and 54% on Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition (MCHN) (Corsi, 2012).

International databases play a crucial role in consolidating and standardizing data from multiple sources, allowing for cross-country comparisons, trend analysis, and evidence-based policymaking on a global scale. Numerous international databases rely on DHS data to estimate prevalence and generate insights on key global issues. Notable examples include the World Bank Database and the UN Data Portal, both of which use DHS data to inform statistical analyses and guide policy development across various sectors.

In sum, since its launch, the DHS has played a crucial role in enabling evidence-based decision-making, strengthening institutional capacity, and supporting international development efforts. Its open, high-quality datasets remain indispensable to monitor global health trends and advance equitable development.

The DHS and DPA

At Data-Pop Alliance (DPA), the DHS has been as a foundational resource for research and action-oriented policy recommendations, particularly to gain insights into patterns of gender-based violence (GBV) and sexual GBV in places where this data would otherwise be limited or non-existant.

For instance, in the 2022 project “Capturing the Socioeconomic and Cultural Drivers of Sexual and Gender-based Violence (SGBV) in Sierra Leone”, DPA used a mixed-methods approach and machine learning techniques to analyze trends, risk factors, and cultural influences behind SGBV. By combining DHS data with qualitative insights, the study identified patterns of prevalence and root causes to better inform prevention strategies.

Similarly, in 2021, DPA conducted the “Liberia Country Gender Equality Profile (CGEP)”,—marking a significant milestone as the first comprehensive gender equality report for the country. This landmark initiative aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of gender disparities across various sectors, including health, education, economic participation, and political representation. A critical component of the CGEP was its analysis of the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately affected women and girls in terms of economic security, access to healthcare, and exposure to gender-based violence. DHS data played a pivotal role in this assessment. It enabled a detailed evaluation of inequalities and helped to map out the areas requiring the most urgent interventions. Importantly, the analysis also identified significant data gaps that hinder a full understanding of gender dynamics in Liberia. Addressing these gaps is essential for designing evidence-based policies and programs that truly advance gender equality.

Beyond these examples, DHS data has been central to many DPA initiatives. Currently, DPA is working with UNFPA to develop the “kNOwVAWdata Training on Harmful Practices”, which trains participants to measure and interpret prevalence data related to harmful practices. The DHS’s comprehensive and standardized methodology remains a critical asset in these efforts.

USAID: A Politicized Pillar of U.S. Foreign Policy

As previously discussed, the DHS Program was established by USAID, which itself was created by President John F. Kennedy during the Cold War as a tool of soft power to counter Soviet influence through foreign assistance. According to Kennedy, the U.S. State Department was too bureaucratic to manage such aid effectively, prompting the creation of a dedicated agency (Knickmeyer & Kinnard, 2025).

Today, USAID continues to be regarded by its supporters as a strategic counterbalance to the growing influence from countries like Russia and China. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, for instance, is active in many of the same countries where the United States seeks geopolitical partnerships (Knickmeyer& Kinnard, 2025). However, since its inception, USAID has remained a contentious issue in American political discourse.

Both international development theorists and U.S. political actors across the aisle have long debated the role of foreign assistance. One perspective argues that aid stabilizes partner countries, curbs irregular migration, and indirectly benefits U.S. security—such as through the practice of “offshoring the border”, which entails extending border control measures beyond the geographic frontier to prevent migrants from reaching it (Vaughan-Williams, 2009). Critics, however, often dismiss such efforts as wasteful. Typically, Republicans have pushed for tighter oversight of USAID under the State Department, while Democrats have advocated for granting USAID greater autonomy and authority (Knickmeyer & Kinnard, 2025).

This debate has shaped the American political imagination, contributing to widespread public misperceptions about the scale of U.S. foreign aid. A 2015 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Americans believed, on average, that 31% of the federal budget went to foreign aid—when the real figure was closer to 1% (Di Julio et al., 2016). A recent poll conducted during the Biden administration continues to reflect that disconnect. Many Americans perceive foreign assistance as excessive, particularly in light of domestic concerns about the economy, military readiness, and border security (The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 2023).

Let us briefly review the data to clarify these misconceptions. The U.S. is projected to allocate approximately $58.4 billion to international assistance in the 2025 fiscal year, though this figure may be revised under the Trump administration. In fiscal year 2023, the U.S. disbursed $71.9 billion in foreign aid, just over 1% of total federal expenditures, slightly down from $74.0 billion in 2022. Since 2008, foreign aid spending has remained relatively stable, ranging between $52.9 billion and $77.3 billion (inflation-adjusted) since 2008 (DeSilver, 2025).

Despite the modest proportion of the federal budget it represents, the U.S. remains the world’s largest donor—accounting for over 40% of all humanitarian aid tracked by the United Nations in 2024 (DeSilver, 2025). Any significant reduction in this funding would therefore have a significant impact on global humanitarian relief and development efforts.

In fiscal year 2023, U.S. foreign assistance supported a wide range of initiatives, including (DeSilver, 2025):

- Disaster relief and other humanitarian aid: $15.6 billion (21.7%)

- HIV/AIDS response: $10.6 billion (14.7%)

- Pandemic, influenza and other public health threats: $1.5 billion (2.0%)

- Democracy and governance initiatives: $2.3 billion (3.2%)

- Multi-sectoral programs: $2.9 billion (4.0%)

Nevertheless, criticism persists. In early 2025, the U.S. government, under the Trump administration, imposed a 90-day freeze on several foreign aid programs to reassess how the funds align with American interests (Associated Press, 2025). This decision affected numerous international aid initiatives, halting support for thousands of people and organizations (Knickmeyer & Kinnard, 2025). The freeze has triggered domestic and international backlash and is currently under judicial review.

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio USAID as “completely unresponsive” (Kent, 2025). and emphasized that its activities should align more directly with national foreign policy goals (Associated Press, 2025). The White House has since released a list of programs it considers examples of “waste and abuse”, including: $1.5 million allocated to “advance diversity, equity, and inclusion in Serbia’s workplaces and business communities,” $47,000 for a “transgender opera” in Colombia, funding for printing “personalized” contraceptive devices in developing countries (The White House, 2025).

These examples are being used to justify a broader reevaluation of USAID’s mission, raising significant concerns about the future of U.S. global development leadership and the long-standing programs it supports—like the DHS.

What Will Happen Now?

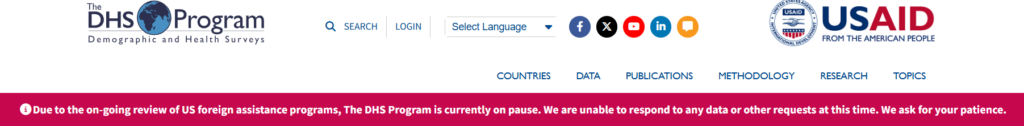

Although the DHS Program was not explicitly named in public statements surrounding the foreign aid freeze, a notice on its website reads: “Due to the ongoing review of U.S. foreign assistance programs, The DHS Program is currently on pause. We are unable to respond to any data or other requests at this time. We ask for your patience.”

This signals a concerning and indefinite halt, in which we are left in a state of limbo, where the future remains unclear. While the full extent of the consequences is not yet clear, what we do know is that many ongoing projects have been put on hold—with no certainty that they will resume. Critical questions remain: What will happen to the data that has already been collected? Will countries have the capacity to independently collect, clean, analyze and publish new data? Will the trust built with communities over decades be lost?

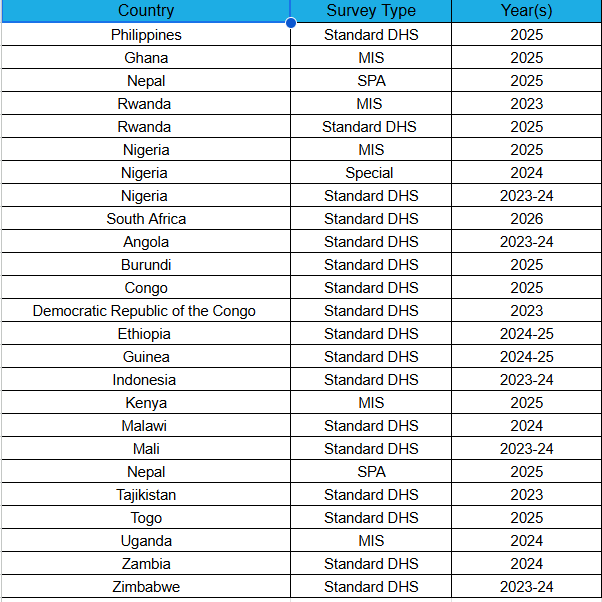

To illustrate the scope of the disruption, the table below presents currently ongoing DHS projects, compiled for this blog using the keyword “ongoing” on the DHS website. These projects span dozens of countries across Africa and Asia. The effects of this freeze will be particularly significant in Western and Eastern Africa, where DHS is often the only source of comprehensive national health data. Most of these initiatives involve household surveys, GIS tools, and in-person interviews—processes that require significant time, expertise, and funding. The suspension threatens to derail this work entirely.

Institutions like The Institute of Tropical Medicine have raised concerns. The sudden disruption in access to data and support not only delays research but also undermines public trust and jeopardizes the training of future scientists. Survey participants, mainly women, shared sensitive personal information with the understanding it would inform research and policy. Withholding or abandoning that data violates both ethical and scientific responsibilities.

This is in addition to the real-world consequences, illustrated by the concrete actions that have been taken to address issues uncovered through DHS data. For instance, when DHS revealed that 55% of rural Cambodian women aged 15–49 who experienced gender-based violence in 2021–22 never sought help, it spurred local and international efforts to strengthen survivor support services. In India, data from the 2019–21 DHS on menstrual health directly shaped the National Menstrual Hygiene Policy, advancing menstrual equity nationwide (Grown, 2025).

While some national health ministries or statistics agencies may hold the raw datasets, in practice, access, storage and comparability are not always guaranteed. Without a centralized data platform, cross-country comparisons and longitudinal tracking of key indicators—essential for monitoring progress on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—are severely limited.

This pause also disrupts training programs for health professionals and researchers, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The long-term consequence is a diminished pipeline of data-literate leaders able to respond to emerging global health challenges.

The suspension or delay of new surveys deprives governments and organizations in LIMCs of essential up-to-date, population-level data on critical issues like gender-based violence, HIV prevalence, vaccine coverage, and maternal mortality. The lack of accessible, timely, high-quality data, decisions risk being made in the dark, undermining transparency, accountability, and impact. It also threatens the identification of critical trends and the analysis of factors like climate change, urbanization, and healthcare access (The Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2025).

What Will Happen Now?

As data researchers and analysts, we recognize the vital role the DHS Program plays in policy implementation, poverty alleviation, and global health interventions. Moreover, DHS data represents real lives, real communities, and complex realities. Its absence creates a vacuum in the infrastructure of evidence-based development. This piece does not offer solutions. However, it does raise the alarm on an urgent and under discussed issue. Without data, we lose sight of those we aim to serve—and with that, we risk losing far more than numbers. We risk lives.

References

Associated Press. (2025, February 1). USAID website goes offline amid Trump administration’s freeze on foreign aid. CNN. USAID website goes offline amid Trump administration’s freeze on foreign aid | CNN Politics.

Corsi, D. J., Neuman, M., Finlay, J. E., & Subramanian, S. V. (2012). Demographic and Health Surveys: A profile. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(6), 1602–1613. Demographic and health surveys: a profile – PubMed.

DeSilver, D. (2025, February 6). What the data says about U.S. foreign aid. Pew Research Center. What the data says about US foreign aid | Pew Research Center

DiJulio, B., Norton, M., & Brodie, M. (2016, January 20). Americans’ views on the U.S. role in global health. The Independent Source for Health Policy Research, Polling, and News. Americans’ Views on the U.S. Role in Global Health | KFF

Fabic, M. S., Choi, Y., & Bird, S. (2012). A systematic review of Demographic and Health Surveys: Data availability and utilization for research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(8), 604–612. A systematic review of Demographic and Health Surveys: data availability and utilization for research – PMC

Goldstone, J. A. (2012). Politics and demography. In Political demography: How population changes are reshaping international security and national politics.

Grown, C. (2025). An ode to the Demographic and Health Survey Program. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/an-ode-to-the-demographic-and-health-survey-program/

Kent, L. (2025, February 4). How the US foreign aid freeze is intensifying humanitarian crises across the globe. CNN. How the US foreign aid freeze is intensifying humanitarian crises across the globe | CNN

Knickmeyer, E., & Kinnard, M. (2025, February 4). What USAID does, and why Trump and Musk want to get rid of it. Associated Press. What USAID does, and why Trump and Musk want to get rid of it | AP News.

Ray, R. (2020). The importance of collecting demographic data. The Brookings Institute.

Seddon, S. (2025, February 7). What is USAID and why is Trump poised to ‘close it down’? BBC News. What is USAID and why does Donald Trump want to end it?

The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. (2023, March). The March 2023 AP-NORC Center Poll. The Associated Press and NORC at the University of Chicago.APNORC_Mar2023_Topline_Budget.pdf

The Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp. (2025, February 13). When health data go dark: A call to restore DHS Program funding. When health data go dark: A call to restore DHS Program funding | Institute of Tropical Medicine.

The White House. (2025, February 3). At USAID, waste and abuse runs deep. At USAID, Waste and Abuse Runs Deep – The White House

Vaughan-Williams, N. (2009). Border politics: The limits of sovereign power. Edinburgh University Press.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)