DISCUSSION PIECE

While Silicon Valley’s tech giants are increasing their investments in Africa, terms like “Data Colonialism,” “Digital Colonialism,” and “AI Colonialism” have been increasingly used to describe the situation at play. When it comes to digitalization in the Global South, particularly relating to AI-based technologies, several scholars, movements, and activists have begun to debate how colonial legacies continue to persist. The notion of “coloniality of power” was first coined by Aníbal Quijano in the late 1990s, and expanded further by Walter Mignolo. For them, modernity and coloniality are simply different aspects of the same phenomenon. Coloniality attempts to provide an explanation for the perpetuation of power relations between the colonized and the colonizers, and how these power dynamics persist in contemporary practices around the world.

In The Costs of Connection, Couldry and Mejias argue that the prolonged effect of the 500 years of colonialism is still being felt in the digital era. According to the book authors, Big Data extraction is the modern-day version of raw material extraction and land acquisition, which colonial powers have used to exploit the colonized countries for nearly five centuries. They call this phenomenon “data colonialism.” Similarly, the scholar Michael Kwet argues that U.S. multinational corporations are re-colonizing the Global South through their dominance over its digital infrastructure including network connectivity, software, and hardware. Moreover, Shakir Mohamed, a South African research scientist at DeepMind, was the first to urge researchers to decolonize Artificial Intelligence (AI) in 2018. Later in 2020, Mohamed, along with Marie-Therese Png, and William Isaac, published a paper in which they explain how colonialism is manifesting in AI and proposed tactics to decolonize it. This piece will explore the history of colonialism, its enduring legacies in Africa, and highlight emerging movements that seek to challenge the existing coloniality of power in the AI industry.

Brief History of European Colonialism

In its earliest iteration, the process of colonizing the so-called “New World” was led by private companies, such as the English Virginia Company and the East India Companies. These colonial enterprises were authorized by the European monarchs and the Pope to extract resources, acquire land, and make profit from the newly discovered territories. The early dominance of the Spanish and Portuguese in the Americas was quickly followed by the involvement of the British, French, and Dutch in various colonial ventures. The English East India Company, established to exploit commercial opportunities in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and India, was involved in the territorial conquest of the Indian Subcontinent as well. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, colonial European powers and enterprises started the systematic enslavement and trade of millions of Africans, where they were coerced to extract resources in the Americas under horrific conditions.

The colonial private appropriation of land, resources, and human beings was followed by the national domestication of the private companies’ operations; European States established their own direct imperial rule over their colonies. Colonialism became a national project for European powers, where exploitation was institutionalized and perpetuated. During the 19th century, North America, South Asia, and several British colonies witnessed the start of railroad colonization. The construction of railroads was financed by public debt secured by land grants and enslaved labor. Not only did the construction of railways aid in expanding the colonization processes in both the United States and India, but they also assisted Britain in maintaining India as the primary market for its manufactured goods. “Colonial drain” was one of the funding methods in settler colonies. This term refers to the taxes and revenues that were collected by colonial powers for their own use, instead of being spent on the colonized territories.

How AI in Africa Perpetuates Coloniality

- The Only Languages That Matter are Western

Language was often one of the first aspects colonizers imposed on the people they subjugated. From the 1500s until the late 1900s, most invaders made a point of outright banning Indigenous languages. Many authors who went to school during colonial rule detailed how students were punished (sometimes physically) for speaking their native language in class. This demonstrates how important language is to a nation’s identity, culture, and history. Today, many Indigenous languages are being forgotten and disregarded in the development of natural language processing (NLP) technologies. Widely spoken African languages like Yoruba, Igbo, and others are not well recognized by NLP features. For example, the Google language application incorrectly translates the Yoruba word “Esu,” which means “a benevolent trickster god,” into “devil.” While both Dutch and Swahili have tens of millions of speakers, a recent paper showed that there are hundreds of scholarly studies on natural language processing in Western European languages, but only approximately 20 in East African languages. Likewise, Facebook still fails to take down posts that contain misinformation and hate speech in non-western countries like Myanmar. Despite the fact that 90% of Facebook’s users are based in countries outside the United States, just 13% of moderation hours were devoted to identifying and removing false content in those regions in 2020. Western-led AI-based systems like NLP do not fit into the cultures or the norms of African countries, for example, and thus maintain the same historical pattern of cultural colonialism that the Global South has endured for centuries.

- Modern Slavery in the AI Industry

AI is a multi-billion-dollar industry that giant tech companies, such as Amazon, rely on heavily. AI is key to the primary revenue streams of Amazon, the most profitable tech company in the world in 2021. Despite that, the workers of Amazon Mechanical Turk , a crowdsourcing website, are poorly paid, with a median hourly wage of $2.83 per hour. Training AI technologies with data is labor-intensive. In order to produce a one-hour video for the computer vision of a self-driving car, hundreds of hours of labeling are done by human workers. These employees are usually invisible to the end user (leading to the term “ghost workers”), face economic vulnerability, and work in remote settings across the globe. According to Shakir Mohamed, the current global post-colonial economic inequalities and the absence of labor regulations in many parts of the Global South are being exploited by large corporations through outsourcing services.

In Nairobi, Kenya, around 200 men and women work for Sama, an AI outsourcing company based in California, which has data-labeling contracts with Google, Facebook, and Microsoft. Sama’s employees are content moderators, meaning they are required to watch graphic footage of murder, rape, suicide, and sexual abuse of children. One of their tasks is to remove illegal content from Facebook. Despite their crucial role in Facebook’s operation and mental health risks they face in the job, they are some of the company’s lowest-paid employees in the world, with some earning as little as $1.50 an hour.

- Ethics Dumping in Africa

Under the guise of science, colonial powers have a long history of taking advantage of marginalized and vulnerable people in the colonized territories, including untested medical experiments under British colonial rule that would eventually lead to new and innovative procedures. In the 19th century, enslaved African Americans were used in various scientific experiments. For example, testing on Black women and infants was applied to advance the field of gynecology (Mohamed, Png and Isaac, 2020). According to Mohamed, Png, and Isaac, AI corporations continue the same inhumane exploitation by testing their predictive systems in other countries that lack data regulations protections. This phenomenon is referred to as “ethics dumping”, which occurs when countries or organizations export their harmful and illegal practices to low- and middle-income countries or vulnerable groups.

A recent example is Cambridge Analytica (CA), who used the 2017 Kenyan and 2015 Nigerian elections as beta-testing grounds for the algorithmic techniques that it would later employ in the US and UK. One obvious form of ethical dumping was CA’s decision to set up its testing operation in countries with less stringent data protection regulations than the country in which it is based, the United Kingdom. It was eventually shown that these systems actively hampered democratic procedures and weakened social bonds. As Mohamed, Png, and Isaac explain, it was only when the violation of democratic procedures by corporations like CA began to harm Western democracies that international attention and mobilization were brought into play.

- Digital Apartheid in South Africa

Despite the end of the apartheid state in South Africa in 1994, various cities in the country remain highly segregated. The northern suburbs of Johannesburg are home to some of the city’s wealthiest white residents. Areas like Soweto and Alexandra, on the other hand, are home to those living in poverty, who are also much more likely to be Black. This segregation dates back centuries, as British colonists used railroad infrastructure to systematically separate white and Black people. Later, in 1948, the Dutch colonists introduced laws that legalized apartheid. 25 years after the end of apartheid and 29 years after Nelson Mandela’s release from jail, Johannesburg is just as segregated as it was before. When it comes to security and crime, segregation still affects who receives protection from crimes and who does not. In general, policing duties in South Africa are mostly dominated by private companies like Vumcam. Those companies do not serve the public interest, but rather clients who pay, and who are more likely to be wealthy and white.

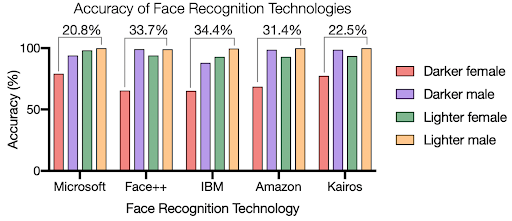

Today, more than 5,000 security cameras are active in Johannesburg, installed by the security company Vumacam. The captured videos taken by the CCTV network are sent to central monitoring stations around the country, where advanced AI technologies, such as license plate trackers, are used to monitor the flow of people and identify specific individuals. In a segregated city like Johannesburg, white people are more likely to be able to afford surveillance, while Black people are less likely to have access to such protection. According to the most recent official statistics, 50% of South Africans were living in poverty in 2015, and of those, 93% were Black. In addition, facial recognition software does not function accurately. The possibility of a false identification by a facial recognition system increases considerably when videos are recorded outdoors, and Black people are particularly vulnerable to this risk. Growing evidence shows that there are significant differences in inaccuracy rates across demographic groups. In a 2018 study called “Gender Shades” an intersectional method was used to evaluate three gender categorization algorithms, including those from IBM and Microsoft. Four groups were used; females with darker skin tones, males with darker skin tones, females with lighter skin tones, and males with lighter skin tones. Error rates were up to 34% higher for darker-skinned females when using any of the three algorithms compared to those for lighter-skinned males (Figure 1 below).

- Africa’s Exclusion from AI Discussions

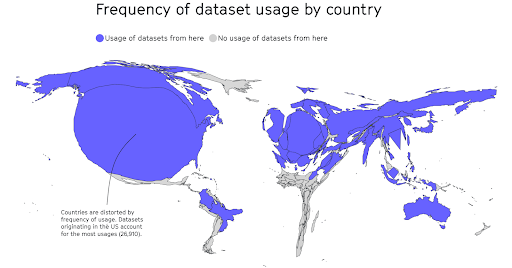

Given the decreasing cost of machine learning (ML) training, as well as the increasing availability of data, there has been growing interest from private companies in AI. Private investments and research and development are key to questions of AI power dynamics. With regard to AI private investments, the United States and China are clearly in the lead. As shown in Figure 2 (below), the datasets that are used to test the performance of ML systems are concentrated in just a few countries, mainly the United States. More than half of the datasets utilized for AI performance evaluation across over 26,000 research articles came from only 12 top universities and tech corporations in the United States, Germany, and Hong Kong. This leads to Mohamed and his colleague’s argument that geographic areas such as Africa, South and Central America, and Central Asia are underrepresented in discussions around AI ethics. This power imbalance leads to economically powerful countries dictating the discourse on AI and who should benefit from it. Additionally, questions about disregarding local knowledge, cultural diversity, and the requirements for global justice are raised. Looking at the spread of national AI legislation in nations around the world, a similar phenomenon is observed. A new sort of geopolitics among AI superpowers is on the rise, in which governments compete to promote their preferred perspective on policy and technological approaches.

How the Global South is Decolonizing AI

A decolonial AI movement has emerged in the Global South in reaction to the increasing influence of tech monopolies and AI technology. Sabelo Mhlambi, a Stanford scholar, and others recently published The AI Decolonial Manyfesto. The Manyfesto provides an opportunity for a variety of perspectives on empowering historically marginalized people to develop their own dignified, socio-technological futures. Mhlambi is also the founder of the AI startup Bhala, whose objective is to make AI accessible to Africans through the use of African languages in NLP systems. Additionally, the African organization Masakhane has made the decolonization of AI and science a top priority. They have regular meetings and conduct their own AI research in order to develop cutting-edge AI systems for use across the continent of Africa. For instance, efforts are being made to improve NLP for a number of languages spoken in East Africa that have traditionally received fewer resources. Instead of waiting for businesses like Google or Microsoft to develop AI systems for them, they are focusing on supporting locals to develop their own final products. This year, they plan to start a fund to help others in their area who are working on AI projects.

Mohamed, Png, and Isaac, similarly, propose three tactics to decolonize AI in their paper. First, the researchers emphasize the importance of context when developing AI technologies. The eventual deployment and application of AI should be thought of in the process. The codes have to be tested according to ethical guidelines. Second, AI developers need to make an effort to listen to underrepresented voices. An emerging way of doing this is known as “participatory machine learning,” which involves the individuals who will be most impacted by AI systems in the design process. Subjects have an opportunity to question and steer the formulation of ML problems, the selection and collection of data, and the application of the resulting models. Third, all members of society, not just the traditionally privileged, should have access to the resources necessary to launch their own AI projects. Deep Learning Indaba, Black in AI, and Queer AI are just a few examples of existing groups of underrepresented AI practitioners whose efforts should be highlighted.

In a seminar organized by Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI), Mhlambi explains that the decolonial narrative is needed to examine and challenge the enduring power structures and institutions that date back to colonial times. The effects of the economic disparities that were created by deliberately impoverishing some continents in order to support the economic development of others are still being felt today. He adds that patterns of AI colonialism, such as the commercialization of automated AI decision-making and the risks it may pose, are not limited to Sub-Saharan Africa, with similar trends occuring in Asia, Latin America, and even the United States. According to Mhlambi, that’s how the global socio-economic system is designed; it can’t survive by only exploiting those who have been traditionally excluded.

Almost concurrently, there has been a reawakening throughout Latin America on the topic of decolonizing AI. A movement called Tierra Común has formed to support this concept. It serves as a central meeting place for people in Latin America to discuss decolonizing data, share ideas, and network with the goal of making a difference, gathering once a month to prepare seminars and newsletters. Tierra Común states that their specific focus is Latin America, but their horizon is the Global South and all the people who reject this new colonialism as the latest manifestation of the desire for domination exercised by the Global North. Similarly, Western academic institutions are now actively engaging with the decolonial AI movements by publishing research, conducting workshops, and awarding fellowships, according to Mhlambi.

Conclusion

The benefits of AI are immeasurable. There is no doubt that AI has the power to address pressing societal issues and enhance quality of life. However, as discussed above, there are several trends, including labor exploitation, ethics dumping, and economic and social segregation that are becoming a reality throughout Africa and the rest of the Global South. Multinational AI corporations are exploiting the legal loopholes related to personal data protection and labor laws to their advantage. Despite the usefulness of AI, its current iteration does not contribute to Africa’s development as much as it perpetuates the systemic exploitation which has been projected onto the continent for centuries. The aforementioned examples of how AI sustains the coloniality of power that was created by colonialism are just some of the many more examples that exist. The same communities and nations that were impoverished by classical colonialism are still being affected by the advent of new technologies, including AI, to this day. It is vital that a level of awareness be created around the world, and specifically in regions affected by colonialism, in order to challenge the unequal power dynamics that are being upheld by tech companies developing AI initiatives. The emerging decolonial AI movements and activists such as Mhlambi, Mohamed and Tierra Común are already fighting to create a more inclusive and just AI landscape for the Global South. These initiatives represent the first steps toward restoring power to those who have traditionally been marginalized and exploited by foreign domination.

About the author: Arwa ElGhadban is a Research and Content Intern with Data-Pop Alliance’s Just Digital Transformations Program. She currently resides in Germany.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)