Data can reveal local realities and empower development actors to drive positive change. However, the methods of data collection are crucial, especially when dealing with complex situations and vulnerable populations. In this blog post, we explore the data collection process behind a project developed by Data-Pop Alliance and UNDP’s Country Offices in the borderland region of Sierra Leone and Liberia—one of the world’s most vulnerable regions due to its historical challenges, economic instability, social marginalization, food insecurity, limited access to basic services, and the impacts of climate change.

The Borderlands Project: A Joint Effort Between DPA and UNDP

The Borderlands Project, officially titled Community-Based Social Protection Mechanisms in Africa’s Borderlands – Liberia and Sierra Leone Case Study, was launched by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2023 and carried out by DPA to document non-state, community-based social protection mechanisms in the borderlands of Liberia and Sierra Leone.

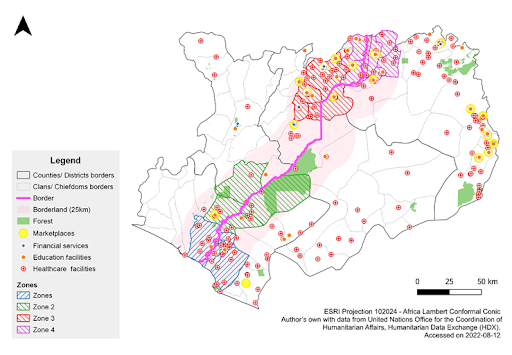

The decision to focus on the borderlands was driven by several factors. These areas—within 25 km of the national borders—are characterized by shared ethnic ties, cross-border trade, and interconnected social histories. Their proximity to the border creates a unique blend of cultures and economies, setting them apart from other regions in both nations. Furthermore, these regions are not only critical zones for trade and interaction between the two nations but have also experienced significant instability due to civil conflicts and economic disruptions. Often marginalized with limited access to essential services and infrastructure, the borderlands are particularly vulnerable to various shocks, including environmental disasters, economic downturns, and health crises like the Ebola outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Amids this landscape, the study established three main objectives:

- To explore how borderland communities cope with both idiosyncratic and widespread shocks;

- To assess the functioning of community-based social protection organizations (CBSPOs); and,

- To identify existing or potential policy linkages between these mechanisms and local or national governments.

Key Findings

The study’s findings offer valuable insights into the shared challenges and coping mechanisms of borderland communities in Liberia and Sierra Leone, as well as the transformative role of Community-Based Social Protection Organizations (CBSPOs). These regions, shaped by deep cross-border ties through trade, marriage, and shared histories, are home to communities that continually adapt to difficult conditions. Over 57% of residents have crossed the border in the past year, highlighting the importance of these connections in fostering peaceful relations and shared livelihoods. However, despite this interconnectedness, these communities face significant challenges in areas such as food security, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Food shortages and family illnesses are among the most immediate stressors impacting borderland households. Long-term difficulties such as limited access to safe drinking water, education, and healthcare services further compound these issues, trapping many families in cycles of poverty. Poor road conditions, especially during the rainy season, limit mobility, hinder economic activities, and restrict access to essential services. These infrastructural gaps exacerbate an already difficult situation, making it harder for communities to trade, generate income, or receive external aid when needed.

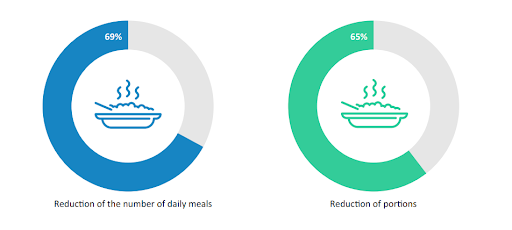

In response to these challenges, households adopt various coping strategies, some of which have long-term negative consequences. Many families, particularly those headed by women, resort to skipping meals, cutting healthcare spending, or taking on additional debt to manage financial stress. Male-headed households generally have more access to both formal and informal support networks, which include CBSPOs and community-driven resources, leaving female-headed households disproportionately vulnerable and more likely to adopt extreme measures to survive.

CBSPOs provide crucial support in these borderland regions, offering services such as savings and loans (preventive), labor-sharing (promotional), and food assistance (protective). These organizations empower communities by offering locally governed, participatory solutions that address the most pressing needs. For example, Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs), types of CBSPOs, contribute to income diversification and financial stability.

However, the structure of CBSPOs also reflects key gender dynamics. Savings and credit societies, like VSLAs, are predominantly female-led, while labor-sharing associations, which provide economic opportunities through communal work, are mostly led by men. Moreover, despite their importance, vulnerable groups—such as the poor, elderly, and young—are often excluded from CBSPOs due to financial barriers or limited social connections. These exclusions highlight the ongoing challenge of ensuring CBSPOs reach those most in need.

In addition to financial hardships, there is a clear divide between the border regions of Liberia and Sierra Leone in terms of access to resources and the role of CBSPOs. Liberian households tend to receive more assistance, though most come from informal sources like friends, family, and community networks. In contrast, Sierra Leonean households face more severe food insecurity but rely more heavily on formal support structures. The study also revealed that CBSPOs in Sierra Leone are more diverse in the range of services they provide, while those in Liberia are more specialized, particularly in offering services related to agricultural support and women’s empowerment.

Despite strong cross-border social ties, collaboration between CBSPOs on either side of the border remains limited. Many CBSPO members are unaware of similar organizations operating just across the border, which restricts opportunities for resource-sharing, coordination, and mutual support. This lack of cross-border collaboration is a missed opportunity to enhance the collective resilience of borderland communities facing similar challenges and goals.

The need for increased government and NGO presence in the borderlands also emerged as a key finding. Communities continue to rely on these institutions to meet needs beyond the capacity of CBSPOs, such as building roads, WASH facilities, schools, and health clinics. However, the support provided remains insufficient, and the infrastructure is often inadequate and not climate-resilient. Most households still primarily depend on informal support from friends and family, followed by CBSPOs, with NGO and international aid lagging behind.

Data Collection in the Global South

Data collection in developing countries, especially in vulnerable and remote regions like the borderlands of Sierra Leone and Liberia, plays a critical role in ensuring that interventions are tailored to the specific needs of the communities. It also provides the necessary depth and breadth of understanding required to capture the unique dynamics of the communities involved in a research project.

For this particular project, the DPA team adopted a multi-phase (parallel-convergent) mixed-methods approach to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. This approach allowed the research team to explore community characteristics, shocks faced by households, coping capabilities, the role of Community-Based Social Protection Organizations (CBSPOs), and key gaps in institutional support.

Each method had a different focus and goals. For example, quantitative surveys were used to target both households and CBSPO leaders, gathering data on demographics, shocks, and governance structures. They also helped identify trends in community needs and social protection mechanisms. On the other hand, the qualitative component of the study involved several methods: focus group discussions (FGDs) with CBSPO and non-CBSPO members to gather group insights on CBSPO participation and dynamics; life history interviews (LHIs) to map personal experiences and key life events affecting resilience; and key informant interviews (KIIs) with local state actors and stakeholders from both governmental and non-governmental bodies to obtain policy-related perspectives.

This comprehensive approach allowed for a detailed understanding of the complex realities in the borderlands of Liberia and Sierra Leone. Combining quantitative surveys with qualitative techniques enabled the project to not only capture large-scale trends in shocks and coping mechanisms but also delve into the individual and group dynamics shaping the resilience of these communities. Finally, the depth and diversity of the data collected through mixed methods provided a nuanced foundation for developing tailored interventions that address both the structural and personal challenges faced by borderland communities.

The Data Collection Process in the Borderlands Project

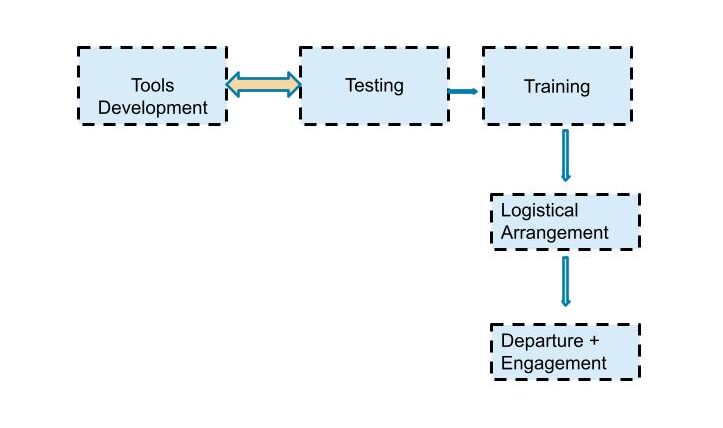

In the context of the Sierra Leone-Liberia Borderlands project, the Data Collection Process (summarized and depicted in the image) followed a structured approach:

- Tools Development: This stage involved the creation of qualitative and quantitative data collection instruments— a key informant interview guide, a focus group discussion guide, a life history interview guide, and the design of two surveys (community-based social protection organization survey and household survey), tailored to project’s needs.

- Testing: The tools were then tested to ensure they were functioning properly and effectively capturing the required information. This phase helps identify any potential issues or modifications needed before large-scale implementation.

- Training: Field data collectors were trained to ensure they understood the tools, the process, and how to accurately gather data. This step was critical in maintaining data quality and consistency, as well as ensuring they could approach people appropriately and convey the study’s goals clearly.

- Logistical Arrangement: Arrangements were made to ensure the smooth implementation of the data collection process. This included securing vehicle arrangements for transportation, coordinating lodging for the field teams, obtaining necessary permissions from local authorities, preparing data collection devices, ensuring Internet connectivity for syncing data, and organizing field supplies such as survey materials, first aid kits, and backup power sources to ensure uninterrupted operations in remote areas.

- Departure + Engagement: The team then departed for a 21-day mission across five areas in the borderlands. In the case of Liberia, Lofa and Grand Cape Mount were targeted, while in Sierra Leone, the team focused on Pujehun, Kailahun, and Kenema. During this phase, the data collection teams engaged directly with the local communities, administering surveys and conducting interviews with local authorities, CBSPO leaders, and community dwellers. These interactions were key to gathering both quantitative data and qualitative insights.

Lessons Learned

Throughout the data collection process in the borderlands region, several key lessons were learned across methodological, practical, cultural, and ethical dimensions. These insights would help refine future data collection approaches and ensure more effective, sensitive, and responsible engagement with local communities in similar contexts.

Methodological: One of the standout achievements from this project, particularly during field data collection, was the local buy-in from key stakeholders, such as elders and chiefs. Their endorsement not only eased tensions but also paved the way for a more cooperative and engaged community. This support demonstrated that early engagement with local leadership is crucial for reducing resistance and ensuring higher participation. In regions where trust in outsiders is often fragile, this approach can be a decisive factor in the success of a project. The smooth mobilization of the community and the absence of any safety incidents—no injuries were reported—highlighted the value of this local collaboration. This lesson is a powerful reminder that building trust through local leadership is not just an option; it’s an essential component of fieldwork success.

However, several challenges emphasized the importance of proper piloting. While the tools used were carefully designed, they fell short in key areas. Lengthy, repetitive questions and unclear phrasing created confusion for participants and enumerators alike, which slowed down the process. Additionally, the completion time for interviews was vastly underestimated—many took over an hour and fifteen minutes, significantly longer than the planned forty-five minutes. This miscalculation caused scheduling issues that required on-the-spot adjustments. Another issue arose when one of the tools went missing during field engagement, underscoring the importance of rigorous planning and resource management. Moreover, the absence of role-playing during training left many enumerators underprepared, resulting in a lack of confidence in the field. These experiences drove home the importance of thorough preparation, testing, and training to ensure a seamless data collection process.

Another critical lesson was the importance of timing. In some areas, data collection coincided with local traditional activities, such as the Sande and Poro society gatherings. This caused further delays and disruptions, as many households were empty, with residents preoccupied with these events. The lesson here is clear: researchers must adapt their schedules to accommodate local activities and rhythms. Additionally, during a life history interview, a participant became emotionally distressed while recalling traumatic memories from the Civil War. This underscored the need to embed counseling services within ethnographic studies. Collecting data on sensitive topics requires more than just asking questions; it demands emotional support for participants who may be reliving painful experiences.

Practical: One of the most significant practical challenges encountered during the data collection was the poor condition of the roads. Conducted during the rainy season, when many roads become nearly impassable, the project faced significant delays and logistical hurdles. In some areas, vehicles could not navigate the muddy and deteriorated roads, forcing the team to walk for up to 30 minutes to reach local communities. This experience highlighted the critical need for contingency planning and the importance of flexibility when operating in remote areas with unreliable infrastructure.

Another practical lesson emerged from the unexpected language barrier encountered during the project. Despite efforts to prepare, it became evident that using local enumerators who understood the local vernacular was essential to overcoming communication challenges. This adaptation allowed for smoother interviews and better data quality, underscoring the importance of employing locals who are not only familiar with the language but also the cultural nuances of the community.

These practical lessons serve as a reminder of the unpredictable nature of fieldwork in developing regions. Researchers must be prepared for infrastructure limitations, unexpected costs, and language barriers, all of which can significantly impact the success of data collection.

Ethical and Cultural: One of the most important lessons learned was the need to respect local customs and cultural sensitivities. In some areas, the use of recording devices or cameras was strictly prohibited, and the research team had to adjust their methods accordingly. This demonstrated the importance of being flexible and willing to adapt to local practices without compromising the integrity of the data collection process. Cultural awareness and adaptability were thus essential.

While informed consent is a cornerstone of ethical research, the project revealed that respecting local leadership was just as important. In many communities, formal consent from participants was insufficient on its own—approval from community elders was needed before participants felt comfortable engaging with the research team. This highlights the need for researchers to honor local power dynamics and integrate these considerations into their ethical framework. Navigating this balance between adhering to international ethical standards and respecting local traditions is critical for ensuring both community cooperation and data integrity.

Language also played a significant role in building rapport. Speaking the local vernacular, rather than formal English, broke down barriers and helped build trust with participants. This small but powerful gesture demonstrated cultural respect and made participants feel more at ease.

Additionally, offering incentives to participants helped strengthen the connection between researchers and the community. In the case of the Gbotiama Farming Cooperative, modest incentives were provided, which fostered goodwill and encouraged participation. This ethical practice demonstrated that participants’ time and contributions were valued, enhancing cooperation and making the overall process smoother.

Conclusion: Why Data Collection Approaches Matters

The success of the Borderlands project highlights the critical importance of using participatory, mixed-methods approaches to truly understand and address the needs of vulnerable communities. More than just gathering data, this approach places the voices and lived experiences of the people at the center of the project, ensuring that solutions are crafted with their direct input. Such methods do more than inform—they empower people, turning research into a collaborative process that fosters trust and builds lasting connections between communities and development actors.

The project also underscored several key lessons that are critical for future research endeavors in similar contexts. First, the importance of local leadership buy-in cannot be overstated—engaging with community leaders from the start ensures broader participation and smoother implementation. Timing is another crucial factor; aligning data collection with local activities and schedules, like market days or cultural events, avoids disruptions and maximizes engagement. Additionally, integrating counseling services into ethnographic research is essential when dealing with communities that have experienced trauma, ensuring that the process is both compassionate and effective.

Click the button below to read the full report, or learn more about our “Resilient Livelihoods and Ecosystems” Program here.

Interested in Working with Us?

If you’re interested in working with Data-Pop Alliance on a project seeking to unveil local realities through data collection and analysis, leveraging ethical, comprehensive and innovative approaches, we welcome the opportunity to collaborate. Whether your work focuses on borderlands, marginalized communities, or vulnerable populations, DPA has a proven track record of designing and implementing data-driven projects that empower communities and inform policy. We can help you design a tailored research approach that addresses the unique challenges in your region, much like our work in the Liberia-Sierra Leone borderlands.

To discuss a potential collaboration, feel free to reach out to us at contact@datapopalliance.org with information on your project’s goals, target communities, and key areas of interest (e.g., poverty, social protection, or gender equity). Together, we can harness data to drive meaningful, lasting change.

About the Author: Nelson Papi Kolliesuah is a Project and Research Officer from Liberia.