DISCUSSION PIECE

It was a calm Tuesday afternoon, my fiance and I had just come back from work and put on our favorite TV show. We were sitting at our dining table, and I noticed it shook. “Please stop shaking your leg!” I said to my fiance, and he replied, “It’s not me, I think it’s an earthqu—” and that was the end of it. The noise that followed was loud; deafening – it was as if the earth was agitated and roared back. I lived fifteen minutes away from the Beirut port, and when I opened my eyes, all of the glass in our apartment was shattered and strewn across the floor. The fallout was apocalyptic. We had stopped thinking about ourselves. We made it, and we were still alive. We were thinking about our loved ones.

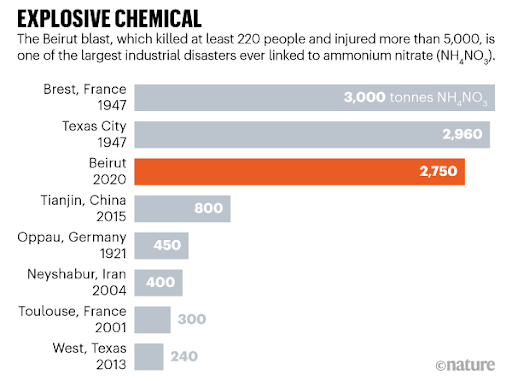

The largest non-nuclear explosion of the twenty-first century was the enormous port explosion that shook Beirut on August 4, 2020 and was caused by the improper storage of ammonium nitrate in the Beirut port. More than 200 people were killed through this negligence, over 6,000 were injured, and more than 300,000 people had to leave their homes. The overall damage from the blast ran in the billions of dollars.

In the past, this chemical has caused major industrial disasters. An explosion at an ammonium nitrate plant in Oppau, Germany, killed 561 people and was heard hundreds of kilometers away in 1921. In 2015, the detonation of approximately 800 tonnes of ammonium nitrate in the Chinese port of Tianjin killed 173 people.

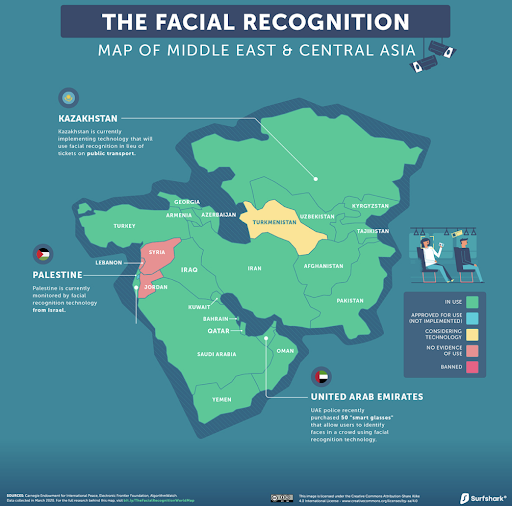

AI-Powered Surveillance Cameras

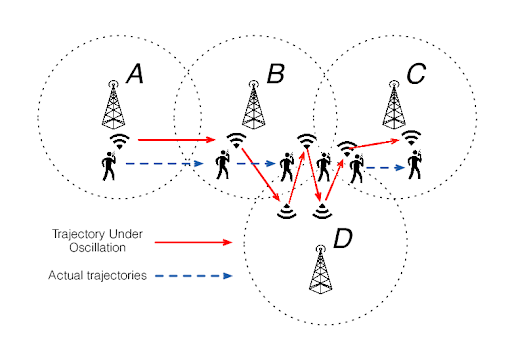

Using Cell Tower Data to Track a Missing Person’s Location

Locating People Through Credit Card Transactions

Banks in Lebanon imposed restrictions on foreign currency withdrawals to $200–$300 per week as a result of demonstrations that began in 2019 in response to the financial crisis. Additionally, cash withdrawals from those accounts were stopped entirely when the COVID-19 pandemic started, and a cap was placed on local currency. As a result of monetary policies implemented by the Central Bank, people are currently unable to withdraw money even from local currency accounts. However, the immediate problem that cardholders are currently facing is the widespread rejection of their cards by businesses. All of Lebanon’s gas stations ceased accepting credit cards at once a few months ago. Then, in an act of unity, supermarkets and food stores imposed a 50/50 policy: they would only accept 50% payment by card and 50% payment by cash. Hence, tracking people by credit card use is quite impossible in this situation. But, in an alternate dimension, credit card data would have been quite useful to track financial activity and thus link people to their last location before the blast, hence tightening the search radius to find them.

Closing Thoughts

While salient privacy concerns exist around all the technologies discussed to find missing persons, they are, in all likelihood, here to stay. Therefore, developing privacy-protecting frameworks that prevent ongoing surveillance but facilitate access to data during specific times and contexts (i.e., utilizing their power for good) is an ideal solution. The disaster in Beirut (and many more that will undoubtedly occur worldwide) demonstrate the ability of these data to aid in various crisis scenarios. It is unfortunate that Lebanon (and many other countries with limited financial resources) do not, or cannot, employ either of these tactics. However, I have faith that we will someday be able to store and use these data sources in safe ways, as I believe in the power of our youth to provide innovative solutions and their drive for change.

About the author: Yasmine Hamdar is a Computational Social Scientist with Data-Pop Alliance. She is Lebanese, and currently resides in the United Arab Emirates.