LINKS WE LIKE #36

Accurate data is pivotal to identifying and responding to the needs of those impacted by a variety of shocks, including violent conflicts, environmental disasters, epidemics, and other life-threatening emergencies. By gathering and processing personal, public, and geographic data, aid organizations, humanitarian workers and other relevant actors are able to not only deploy more targeted responses to ongoing crises, but also develop risk reduction strategies based on previously identified patterns. Despite its crucial role in identifying and assessing crisis situations —if mishandled— data can also lead to serious negative outcomes for already vulnerable groups. For instance, in 2021 Human Rights Watch reported that the Government of Myanmar accessed private information on Rohingya refugees (including biometric data) four years after UNHCR’s creation of a detailed database for this persecuted population. It is therefore imperative that organizations are prepared to responsibly and ethically manage their data collection and assessment methods in order to prevent a variety of risks that may arise from such mismanagement. Nevertheless, there is a growing need for data in the humanitarian sector, as the lack of precise information may result in inequitable and imprecise responses that are likewise harmful to the crisis-affected populations.

Using data for humanitarian emergencies

In terms of how traditional and non-traditional data has been used to assist in humanitarian crises, there are several examples that show just how valuable this information is to first responders and those working to develop assistance strategies. Several organizations such as Doctors Without Borders, the Red Cross, the United Nations Children’s Fund, Crisis Ready and OCHA are actively working towards gathering and making available accurate and timely information to manage different types of crises. Some examples include OCHA’s Humanitarian Data Exchange portal; the Relief Web to provide 24-hour coverage of different crises to help guide the international aid community; the Migration Portal from the International Organization for Migration Global Migration Data Analysis Center which provided timely, comprehensive migration statistics globally.; and the Digital Humanitarian Network, which supports humanitarian responses through digital networks. UNHCR also runs the Operational Data Portal (ODP), which was created in 2011 to collect information and data to help facilitate coordination during refugee emergencies. This portal contains information on several different refugee crises, including the current situation unfolding in Ukraine, and maps daily refugee influxes towards destination countries. In addition to the valuable work of these large organizations, there have been several instances where different actors have created very useful crisis response tools. One key example was the creation of Ushahidi, a non-profit that used crowdsourcing to develop an interactive mapping platform to plot outbreaks of violence following the 2008 Kenyan presidential election. It was also used after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, allowing first responders to locate victims much more quickly with the information it provided. UN Global Pulse and UNCHR Innovation Service also conducted a project using Twitter data to understand the utility of data-driven evidence into decision-making processes, particularly in developing policies to address xenophobia, discrimination and racism towards migrants and refugees in Europe after 2015.

Using digital technology for humanitarian emergencies

Additionally, there are a myriad of digital technologies, including mobile applications, chatbots, unmanned aerial vehicles and biometrics, that can be leveraged to aid communities affected by humanitarian crises. For example, WFP (together with the Government of Jordan, Mastercard, UNHCR, Cairo Amman Bank and IrisGuard Inc.) introduced iris scan payments in Jordan’s Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps through the Building Blocks program, which enabled 1.5 million Syrian refugees to use digital money to buy food and access basic services with an eye scan. The WFP also used mVAM to set up an SMS survey in 2013 to collect data on the effects of the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia, despite movement restrictions on humanitarian staff. Using surveys reduced data collection costs by 50% versus face-to-face interviews. Another example is the Safety Check Service, offered by Meta, which provides user-generated data on who is in danger after a natural or humanitarian disaster. The Missing Maps initiative, a collective of different organizations and volunteers, was key in helping the International Committee of the Red Cross in providing assistance to the over 230,000 people affected by the flooding in Malawi in 2015 who were located in unmapped areas of the country.

Risks in using data and digital technology with at-risk populations

Although these initiatives and projects have been tremendously helpful in dealing with humanitarian emergencies, they also pose risks that can further endanger already vulnerable populations. Particularly in the case of refugee emergencies, data with too much visibility can compromise existing legal rights and procedural guarantees that are necessary to safeguard their lives. In such cases, the organizations involved in collecting and using this type of data have the responsibility to ensure that these risks are mitigated. Regarding the currently unfolding Ukrainian crisis, Google Maps made the decision to stop providing live traffic data in order to protect Ukrainian civilians who have not fled the country. These actions demonstrate the importance of being aware of the ethical and safety concerns of using new technologies during humanitarian emergencies.

Join us in this edition of Links We Like as we explore the promise of new technologies to aid in the response to humanitarian crises, as well as the ethical concerns and risks that accompany the use of these technologies.

This United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) report comes amidst the backdrop of ever-increasing need for humanitarian aid, with individuals requiring assistance growing from 78 million in 2015 to over 235 million in 2021 (and this was before the recent outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2022). The report highlights that while funding has also increased, it is impossible for those funds to “keep up”, but rather must be made to go farther. The report argues one way to achieve this is through the use of digital technologies for humanitarian endeavors. Some of these include AI, mobile applications, chatbots, social media, unmanned vehicles and biometrics. The report details the promise that each of these (and other) technologies has shown, including during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it also highlights the risks involved in their adoption, again looking to COVID as an example. Additionally, the question of digital access also becomes more salient, as those in the most need may also be the most deprived of access to digital technologies. Based on interviews with sector experts, it is divided into 3 sections, covering opportunities and challenges, enablers of adoption, and recommendations for future project design. Overall, this interesting and timely study provides a helpful overview of what the future of humanitarian aid may look like.

This episode of The New Humanitarian’s “Fixing Aid” podcasts takes us to Afghanistan, a country facing an ever-worsening and multifaceted humanitarian crisis following the Taliban takeover in 2021. The sheer scale of the economic collapse (in a country already facing instability) is hard to comprehend, including half a million jobs lost (14% of those employed), and countless more who haven’t received a salary in months. Members of the Afghan diaspora community often watch with frustration and helplessness from abroad as their home country encounters increasing economic and social devastation. Against this backdrop, one former Afghan refugee, Nasrat Khalid, whose family eventually settled in the United States, found himself in a unique position to offer assistance. Nasrat, founder of the e-commerce company Aseel, which formerly sold Afghan arts and crafts, pivoted to a platform for aid delivery. He tells the story of his company, originally conceived as a way to directly increase the incomes of artisans in the country (in addition to showing the world a different “face” of Afghanistan, outside of dire headlines). However, following the US military withdrawal from the country in 2021, the company shifted its focus. The staff within Afghanistan visited refugee camps and asked former artisans what they needed now, which was most often basic necessities and food. The direct connection between the company and those facing hardship proved to be an effective model. Overall, this interesting podcast highlights how innovative new approaches can help in even the most dire of humanitarian crises.

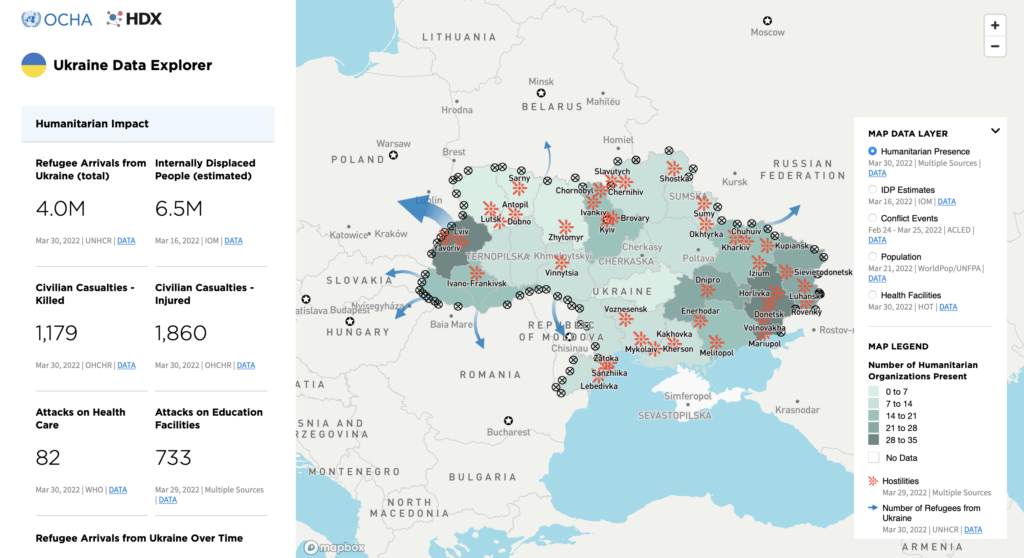

The Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX) is a platform that compiles and shares humanitarian data from different organizations. The organization is part of OCHA/UN Secretariat. Humanitarian data relates to: the context in which a humanitarian crisis takes place; the people affected by the crisis; and the response from institutions providing aid. The HDX compiles databases on more than 254 locations from 1758 sources and special data visualizations platforms for situations such as the COVID-19 and Ukraine Crisis.

Ukraine Data Explorer: This is a platform maintained by HDX, which provides updated information about humanitarian impact, funding, and conflict events in Ukraine. In the Humanitarian Impact section, users can check the number of civilians killed or injured in attacks on healthcare or education facilities, and the number of refugees and internally displaced people. The platform also provides various interactive maps on attacks, which distinguish between battles, attacks against militaries, and violence towards civilians. This initiative is valuable for humanitarian response for several reasons. In short, it provides compiled data and indicates where action is most needed, and may serve as a guide for humanitarian organizations on-site or sending aid from outside the country. For example, the platform points out the number of humanitarian organizations across different parts of the countries and the “hot spots” of attacks, indicating where humanitarian assistance is scarce and, therefore, more needed.

In the past decades, the literature on the subject has come to the agreement that conflict and violence against women and girls (VAWG) are interlinked. Authors explain that often women’s bodies are used as weapons of war, thus becoming another space for battle and destruction. As a result, several organizations have attempted to measure the phenomenon of gender-based violence in the context of armed social conflict. This toolkit provides a framework to implement data collection efforts during such events and afterwards, as well as guidelines and links to other resources.

The overflow of information stemming from computers, cellphones, social media, news, drones, sensors and satellite images that takes place in the wake of a disaster is now so overwhelming that it can prevent policy makers and aid workers from action. This book offers a guide to help practitioners make sense of this large stream of Big Data that is created during humanitarian crises. The book also discusses the role of digital humanitarians, who can be volunteers, students or professionals capable of processing and analyzing this data, to help humanitarian organizations when these skills are needed. Overall, this is an excellent resource created by an expert in the field.

In Jordan, about 83% of Syrian refugees have been registered using biometric technology. This has strengthened the abilities of the government and humanitarian agencies in providing cash assistance to refugees. This technology is particularly useful in cash transfer programs, as it ensures that the correct recipient receives the cash. The use of this technology minimizes fraud, promotes quality assurance and encourages confidence in countries receiving vulnerable refugees for resettlement. Evidence revealed that biometric technology is more accurate and reliable than more traditional approaches as it leads to a more secure IDs, prevents identity theft and can streamline processes by eliminating the need for multiple registrations by various organisations. It enables institutions to benefit from accuracy and unparalleled security of sensitive information. The importance of biometric has also been acknowledged in Uganda, as it has been shown to reduce fraud and enable larger amounts of aid to be delivered more securely. Despite these benefits, there are opposing views that this technology works well for countries with established digital infrastructure and would have low adoption and efficacies in managing humanitarian crises in areas with poor digital infrastructure.

Further Afield

Ukraine crisis

- How are the big tech companies responding to the invasion of Ukraine?

- Ukraine refugee situation

- Digital technology and the war in Ukraine

- Updates: How Tech Organizations Are Supporting Ukraine

- We Urge Satellite Imagery Firms and Space Agencies to Stand With Ukraine

- The Cyber Front in the War on Ukraine

- Ukraine: Migration Statistics, Policy and Humanitarian Responses

Digital technologies for humanitarian emergencies

- Decode Surveillance NYC

- Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team

- Malaria Elimination Mapping

- Microsoft – AI for Humanitarian Action

- The role of digital technologies in humanitarian law, policy and action: Charting a path forward

- How Syrians Pioneered Digital Tools to Stand Up to Authorities

- Digital Technologies Could Help Uganda’s Economy Recover Faster

- Five ways mobile technology can help in humanitarian emergencies

- New report suggests ways to use technology to improve aid in humanitarian emergencies

- In this age of climate crisis, humanitarians need to learn to love tech

- NetHope Announces $15 Million Digital Breakthrough Initiative with Support from Cisco

- Strengthening Disaster Risk Management and Transport Infrastructure after a Disaster: The 2010 Haiti Post-Earthquake Experience

- From digital promise to frontline practice: new and emerging technologies in humanitarian action

- Technological innovation for humanitarian aid and assistance

- Digital Technologies and Humanitarian Action in Armed Conflict

Data for humanitarian emergencies

- Crisis Ready

- DIGITAL HUMANITARIANISM: USING BIG DATA

- The Humanitarian Data Exchange

- From big data to humanitarian-in-the-loop algorithms

- Reinforcing Haiti’s capacities and resilience through quick data collection

- UN warns of impact of smart borders on refugees: ‘Data collection isn’t apolitical’

- The UN’s refugee data shame

- Crisis analytics: big data-driven crisis response

AI and machine learning for humanitarian emergencies

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)