DISCUSSION PIECE

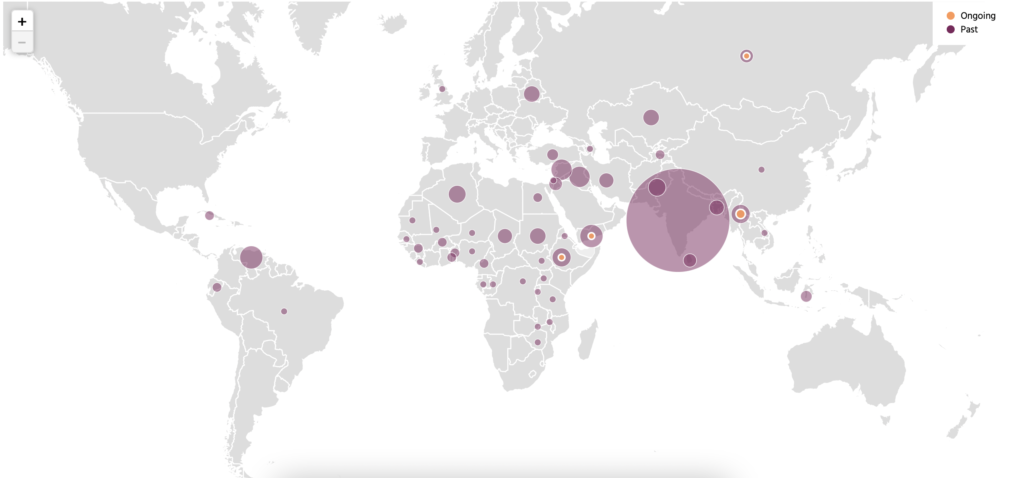

At the beginning of 2022, the Kazakh government removed the price cap on fuel, leading to protest movements in the Central Asian republic. The population has long been dissatisfied with the regime, but the increase in natural gas prices, which the Kazakhs rely heavily upon, was the straw that broke the camel’s back. On the one side were thousands of protesters organizing themselves in the streets; on the other, the “consolidated authoritarian regime”, which was trying to suppress the uprisings by controversial means: On January 4, 2022, NetBlocks confirmed a significant internet outage, disrupting mobile internet and messaging services. The day after, this extended to a nation-wide blackout, lasting for almost a week, with short breaks that enabled strategic top-down communication within the regime. In the last few years, these so-called “kill-switches” have gained in popularity. Regimes are increasingly making use of internet shutdowns and other data-controlling measures to silence citizens. As depicted below, Internet Society uses data from Access Now to visualize internet shutdowns in real-time. The Kazakh example demonstrates the power that information and communication technologies (ICTs) can have. On the one hand, they help organize protests, social movements, and even entire revolutions, while on the other hand, their state-led misuse and control can pose a threat to societal rights and freedoms.

The Citizens’ Side: Contagious ICTs

Protests are one important way of showing resistance to a governing regime. In democracies, these are seen as a form of political participation; the right of citizens to gather and express their opinions. In autocratic countries, however, protests are much less frequent, as open political dissent of any kind may lead to severe consequences. The motives for protest are numerous, ranging from fighting social inequalities, exemplified by the yellow vest movement in France, to defending human rights. Not long ago, in March 2019, the fear of being increasingly incorporated into China’s political system led millions of Hong Kong citizens onto the streets to march in defense of their rights, such as press freedom and freedom of speech.

New media channels, enabled through the fast adoption of ICTs, have significantly influenced the protest landscape. The use of social media seems to be crucial in triggering protest by communicating regime misbehavior to a broad audience. Whereas decades ago, leaflets and traditional media, such as newspapers and television, contributed to the formation and spread of protest, nowadays, social media and messaging services have replaced those mediums with regards to protest organization. With the widespread use of mobile devices, traditional media has been (partially) replaced by social media. These new platforms and messaging services, such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or Whatsapp, allow for the rapid spread of (mostly) unfiltered information and the uncoordinated organization of online activism. Social media helps spread messages that create a so-called “shared awareness” or common understanding. Subsequently, a public consciousness about (a) certain issue(s) can be raised. As an example, the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement achieved considerable offline mobilization in part due to what is known as “hashtag activism” on social media platforms.

Whereas some argue that online political activism, sometimes called “slacktivism”, has only a negligible effect, recent studies in autocratic countries have shown that there is an association between online activism and offline political mobilization. Social media, especially Twitter and Facebook, are said to have been key in “organizing, motivating, and directing” protestors during Egypt’s revolution in 2012. Steinert-Threlkeld et. al (2015), for instance, found that during the Arab Spring, a high number of tweets with certain hashtags preceded protest incidents which occurred the following day. And a study on Russia, Iran, and Egypt showed that a higher level of internet penetration paired with recent protests in one place made subsequent protests in other places more likely. Though the effect of ICTs on offline mobilization is still ambiguous: the persistence of protest over time and its spatial diffusion seems indeed to be related to a higher level of internet penetration in autocratic countries. Conversely, protest occurrence itself is less likely under higher levels of internet penetration. This is due to the fact that not only the opposition makes use of digital technologies in their fight, but also governments know how to deteriorate the dissidents’ position via those technologies. Therefore, one must be cautious in framing ICTs as exclusively empowering in the fight against autocratic regimes.

The Regime’s Side: Containing ICTs

There are two main methods by which autocratic regimes have contained protest movements in the past. The first can be understood as targeted repression. The increased use of ICTs, and the resulting constant creation of data, be it location data, private conversations, or photos and documents, makes individuals much more vulnerable to government surveillance. The NSO Group’s spyware “Pegasus”, for instance, has been used by autocratic regimes (and others) to target civil society actors, thus resulting in the violation of human rights. The Assad regime in Syria has a long history of spying on their own population. Surveilling key dissidents, such as journalists, human-rights activists, and opposition politicians, helps governments to understand their opposition, detect mobilization, and mitigate the threat they pose to the autocratic order.

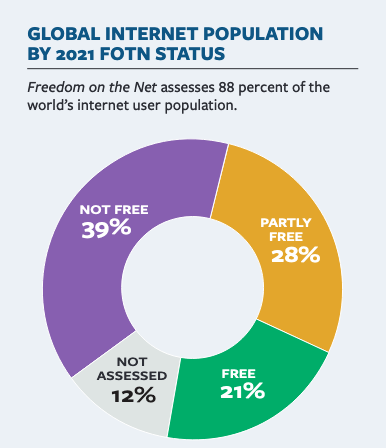

The second instrument to contain protest can be understood as untargeted repression. One instrument thereof is censorship, which often includes prohibiting certain webpages, banning social media services, or blocking VPNs, among others. Currently, roughly 80% of the world’s population live in countries where the internet is either only “partly free” or even “not free” at all (as depicted in the figure below.)

This allows regimes to permit only highly biased pro-regime content to be viewed, often paired with disinformation. Disinformation is understood as “[information] that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organisation or country.” The strategic use of false information by autocratic regimes can paralyze civil society and inhibit activists to organize protests.

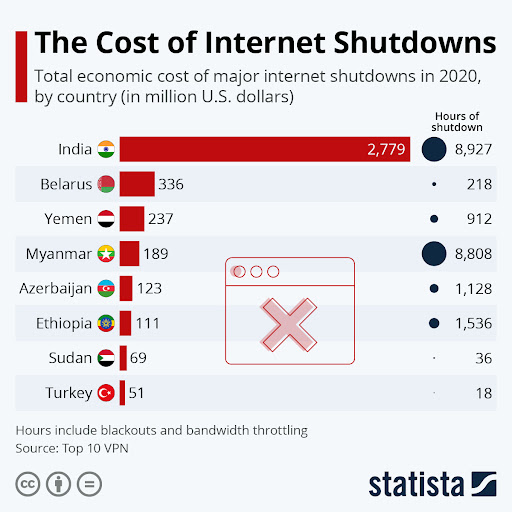

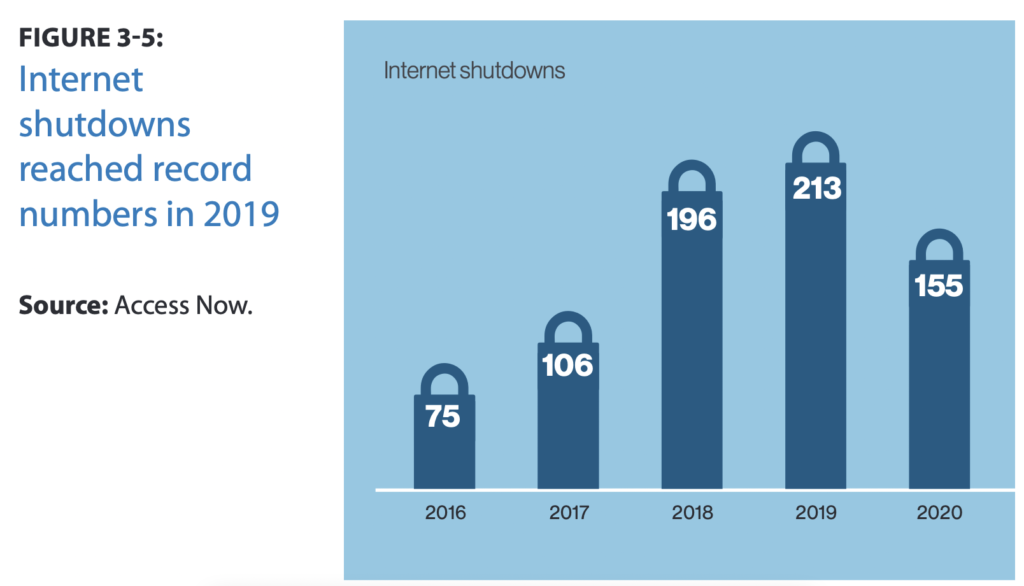

Another technique of untargeted repression, suppressing freedom of expression and press, is curbing the internet or a full “kill switch”. Kazakhstan has been the most recent example, but internet shutdowns are becoming a more commonly employed strategic measure in countering dissidents (as shown in the figures below). In 2011, during the Arab Spring uprisings, the Egyptian regime cut off the internet connection for five days; and in 2019, the Sudanese government used a stepwise shutdown, first partial, and later full.

Although limited in time and space, internet shutdowns have widespread implications, especially for civil society. Gohdes (2015) investigated the relationship between violence and internet accessibility under the Syrian regime. She finds that while no restriction on internet access by the government was more likely to result in targeted regime violence, internet shutdowns were more likely followed by non targeted violence campaigns. The latter is alarming in two ways. First, indiscriminate violence usually leads to more casualties, as its aim is to deter others from joining (protest) movements by inciting fear. And second, there is a concern that internet shutdowns impede the (real-time) reporting of potential war-crimes. The latter might sound negligible in the first place but can become very important when facing future lawsuits before the International Criminal Court, for example.

Beyond silencing dissent, the impacts of internet shutdowns are manifold, ranging from socioeconomic to life-threatening in their impact. Nowadays, hospitals (as well as emergency services) rely on the internet to provide medical assistance. In view of the COVID-19 pandemic, where test results are in digital format and contact tracing is key to prevent the virus’ spread, internet shutdowns can fuel infection rates. Furthermore, the advances that have been made in the field of education, due to increased online access, are curbed by switching off the internet for days or even weeks, therefore worsening the consequences of month-long lockdowns of schools due to the coronavirus. Finally, the global costs associated with internet shutdowns have risen to billions of US dollars, with India leading the amount of internet shutdown hours and costs (see figure below). In 2021, the costs went up again by 36% to $5.45 billion.

These negative economic effects can be explained by businesses being partially forced to stop their operations, banking transactions that cannot be carried out, and informal work relying on internet services becoming disabled immediately. Nevertheless, neither economic costs nor strategies of publicly shaming seem to have a decelerating effect on the global number of internet shutdowns implemented by governments.

Good Versus Bad Shutdowns?

Thus far most of the examples presented of internet shutdowns have concentrated on autocracies, however, it is important to note that democratic states have also made use of this tactic. In 2011, San Francisco’s (ironically the heartland of internet freedom) mobile services at four subway stations were suspended to contain protests related to an unarmed passenger who had been shot by the police the month prior. Although highly criticized, this raises the question of whether there are legitimate reasons to employ internet shutdowns. Can there be something like “good-faith internet shutdown”? Gregorio and Stremlau (2020) argue that increasing polarization on social media, paired with instigations of violence by extremist groups, might be a reason to legitimately utilize internet shutdowns, including within democratic states. This is very much in line with concerns about public safety. I argue that internet shutdowns, even local versions, should never be used by democratic governments to prevent or mitigate demonstrations and protests. Considering the fundamental rights of democracies, freedom of speech and assembly, the untargeted restriction of internet access is not only unjustified, but also unethical.

Even in light of my views, there are reasons to at least discuss the use of shutdowns as legitimate means, such as preventing terrorist groups from coordinating their activities. Jacob and Akpan (2015) investigated the effects of shutting down mobile telephony in certain areas of Nigeria, a military operation against the terrorist organization Boko Haram. This shutdown not only affected the terrorist group itself, but also society. Despite the fact that from a military perspective the operation was considered as successful, citizens had a different view. During the shutdown, people were more concerned and afraid that something might happen to people close to them, without the possibility of communicating with others. Furthermore, frustration arose due to economic consequences for the citizens. Boko Haram itself took the momentum to change their tactics from a previously more “open, cell or networked system” into a “more closed, centralized system.” Hence, while the shutdown might have been justified by a very short-term success, it seemed to have backfired. A more closed and centralized Boko Haram will be way more difficult to defeat in the future. Consequently, the above described “good-faith shutdowns” have not shown to be particularly effective. There is clearly a need to discuss the issue on a broader stage and be transparent about the potential impacts that such operations can have.

The Way Ahead

Within this piece, the protest-enabling role of ICTs for citizens in autocratic states (and occasionally their democratic counterparts) has been discussed, leading to the conclusion that the different uses of the internet indeed might empower protest persistence and diffusion but hinder its first occurrence. Autocratic regimes, in turn, also increasingly make use of ICTs, either by controlling the flow of information and spying on targeted individuals, or by restricting access to the internet. The latter can be observed, especially during times of civil unrest.

Research has shown how important it is to examine the multiple –harmful (but also potentially positive)– impacts of internet shutdowns. Democratic governments should follow the call of civil rights activists in refraining from restricting access to the internet that affects social mobilization. Other settings need to be considered cautiously with all their potential impacts. To date, there is no instrument to prevent the shutdown behavior of autocratic regimes. Additionally, in view of the ongoing fragmentation of the internet, such as China’s “Great Firewall” or Russia’s “RuNet”, the prospects are rather pessimistic. Nevertheless, naming and shaming, as well as collecting as much data-driven evidence as possible of violence campaigns during internet shutdowns, are still important signals to the international community regarding this increasingly salient topic.

About the author: Fabiola Schwartz is a German Research and Content Intern at Data-Pop Alliance currently pursuing an MSc in Politics and Technology at the Technical University of Munich.

References

- Abdulla, R. A. (2011). The Revolution Will Be Tweeted. The Cairo Review of Global Affairs. https://www.thecairoreview.com/essays/the-revolution-will-be-tweeted/

- Andrews, K. T., & Biggs, M. (2006). The Dynamics of Protest Diffusion: Movement Organizations, Social Networks, and News Media in the 1960 Sit-Ins. American Sociological Review, 71(5), 752–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100503

- Bonilla, Y., & Rosa, J. (2015). #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist, 42(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12112

- Buchholz, K. (2021, January 6). The Cost of Internet Shutdowns. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/23864/estimated-cost-of-internet-shutdowns-by-country/

- Caren, N., Andrews, K. T., & Lu, T. (2020). Contemporary Social Movements in a Hybrid Media Environment. Annual Review of Sociology, 46(1), 443–465. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054627

- de Gregorio, G., & Stremlau, N. (2020). Internet Shutdowns and the Limits of Law. International Journal of Communication, 14, 1–19.

- Freedom House. (n.d.). Countries and Territories. Freedom House. Retrieved March 6, 2022, from https://freedomhouse.org/countries/nations-transit/scores

- Gladwell, M. (2010, October 4). Small Change. Why the revolution will not be tweeted. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/10/04/small-change-malcolm-gladwell

- Gläßel, C., & Paula, K. (2019). Sometimes Less Is More: Censorship, News Falsification, and Disapproval in 1989 East Germany. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12501

- Gohdes, A. R. (2020). Repression Technology: Internet Accessibility and State Violence. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 488–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12509

- Hu, M. (2022, January 25). Kazakhstan’s Internet Shutdown is the Latest Episode in an Ominous Trend: Digital Authoritarianism. Nextgov. https://www.nextgov.com/policy/2022/01/kazakhstans-internet-shutdown-latest-episode-ominous-trend-digital-authoritarianism/361073/

- Internet Society. (2022, March 21). Internet Shutdowns. Internet Society Pulse. https://pulse.internetsociety.org/shutdowns

- Jacob, J. U.-U., & Akpan, I. (2015). Silencing Boko Haram: Mobile Phone Blackout and Counterinsurgency in Nigeria’s Northeast region. Stability: International Journal of Security & Development. https://doi.org/10.5334/STA.EY

- Jigsaw. (2020). The Internet Shutdowns Issue (No. 4; The Current). Google. https://jigsaw.google.com/the-current/shutdown/

- Le Goff, C. (2020, February 27). Yellow vests, rising violence—What’s happening in France? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/02/france-protests-yellow-vests-today/

- Marczak, B., Scott-Railton, J., McKune, S., Razzak, B. A., & Deibert, R. (2018, September 18). Hide and Seek. Tracking NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware to Operations in 45 Countries. Citizen Lab. https://citizenlab.ca/2018/09/hide-and-seek-tracking-nso-groups-pegasus-spyware-to-operations-in-45-countries/

- Morozov, E. (2011). The Net Delusion. The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. Perseus Books.

- Netblocks. (2022, January 4). Internet disrupted in Kazakhstan as energy protests escalate. Netblocks. https://netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-kazakhstan-amid-energy-price-protests-oy9YQgy3

- Shahbaz, A., & Funk, A. (2021). The Global Drive to Control Big Tech. (Freedom on the Net 2021). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/FOTN_2021_Complete_Booklet_09162021_FINAL_UPDATED.pdf

- Shirky, C. (2008). Here Comes Everybody. The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. Penguin Press.

- Shirky, C. (2011). The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change. Foreign Affairs, 90(1), 28–41.

- Steinert-Threlkeld, Z. C., Mocanu, D., Vespignani, A., & Fowler, J. (2015). Online social networks and offline protest. EPJ Data Science, 4(19). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjds/s13688-015-0056-y

- Sutton, J., Butcher, C. R., & Svensson, I. (2014). Explaining political jiu-jitsu: Institution-building and the outcomes of regime violence against unarmed protests. Journal of Peace Research, 51, 559–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343314531004

- Toiken, S. (2022, January 2). Жители Жанаозена перекрыли дорогу, протестуя против повышения цен на газ. Radio Azattyk. https://rus.azattyq.org/a/31636220.html

- UNESCO. (n.d.). Journalism, “Fake News” and Disinformation: A Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. UNESCO. Retrieved March 21, 2022, from https://en.unesco.org/fightfakenews

- UNESCO. (2022). Journalism is a public good: World trends in freedom of expression and media development; Global report 2021/2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380618

- Weidmann, N. B., & Rød, E. G. (2019). The Internet and Political Protest in Autocracies. Oxford University Press.

- Woodhams, S., & Migliano, S. (2022, February 1). Government Internet Shutdowns Have Cost Over $18 Billion Since 2019. Top10VPN. https://www.top10vpn.com/research/cost-of-internet-shutdowns/

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)