DISCUSSION PIECE

Women are often on the front lines of disasters, both in experiencing their impacts and in being powerful agents of change. According to the UNDP, women and children are 14 times more likely to die during natural disasters compared to men. Women are too commonly portrayed as either victims or passive beneficiaries because they bear the brunt of a disaster’s consequences. However, women are also essential stakeholders in disaster risk management. Given the right information and tools, women can exercise their agency and potential in building back better after a disaster has struck.

In today’s digital society, information is key in empowering women and girls. Information and communications technology (ICT) has been widely recognized as an indispensable tool in responding to disasters and mitigating its gender-differentiated impacts. By equipping women with greater access to ICT tools and services, they can better prepare for possible disasters, respond more rapidly, and recover more quickly. Therefore, strengthening disaster resilience means bridging the digital gender divide that prevents women from equally harnessing the power of ICTs.

The Link Between Gender and Disasters

Natural disasters are not isolated events, and their impacts are never entirely “natural”, but are determined by the unequal structures and power dynamics in society. As the frequency of natural disasters has increased in the last decade due to climate change, it becomes even more crucial to integrate gender in disaster response. The better we understand the underlying factors driving these gender-differentiated outcomes of disasters, the more effectively disaster risk reduction and mitigation interventions can be designed to enhance resilience for all groups.

Gender inequalities (intersecting with other factors) increase women’s vulnerability to natural disasters. It is not because women are inherently more prone to natural hazards that their mortality during disasters is higher, but rather how they navigate disasters within the pre-existing social and cultural demands expected from them that make them more vulnerable. These vulnerabilities are socially constructed according to the roles and expectations that men and women have traditionally assumed: women are the primary caregivers with the most responsibilities within the household, while men are typically seen as the decision-makers with greater control over key resources. Stereotypical gender roles, norms, and beliefs shape how men and women prepare for disasters, as well as how they respond to them and recover from them. These impacts, in turn, often result in unequal distributions of power and opportunities even among men and women living within the same household. Due to these inequalities, women are affected in a wide range of areas, including health, education, nutrition, and job security, with these impacts being felt even long after a disaster is over.

Disasters also exacerbate gender-based violence (GBV) – which is one of the most pervasive violations of human rights in the world. Extreme climate hazards both increase the pre-existing GBV risk factors for women and girls and decrease the means of protection available to them. Although there are many parallels between the GBV risks associated with various disaster settings, there are crucial differences to consider when comparing slow-onset events to acute catastrophes. Evidence suggests that women’s limited economic power and economic dependency on climate-sensitive work (e.g. farming) makes them vulnerable to slow-onset climate events, such as droughts, which in turn contribute to food scarcity. Under these stressful conditions, communities tend to adopt more conservative and patriarchal attitudes, while additional workloads shared with already present domestic demands may also increase tension within the household. On the other hand, women are also more at-risk of GBV during acute disasters (such as cyclones, floods, or wildfires) because many social protection and life-saving services are disrupted during such events (e.g. sexual and reproductive health care, GBV response, financial relief and access to credit, etc.) Acute disasters further affect mobility, as these can trigger the displacement and migration of women and increase their exposure to GBV in refugee camps or transit zones. Displaced women and girls may also resort to child marriage or transactional sex in situations of scarcity.

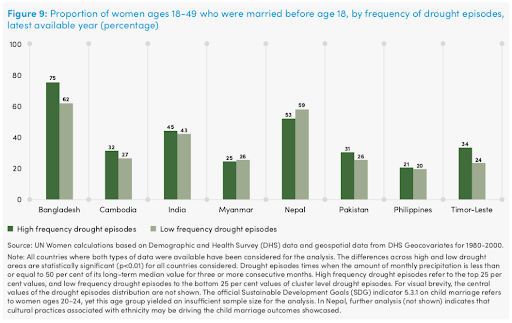

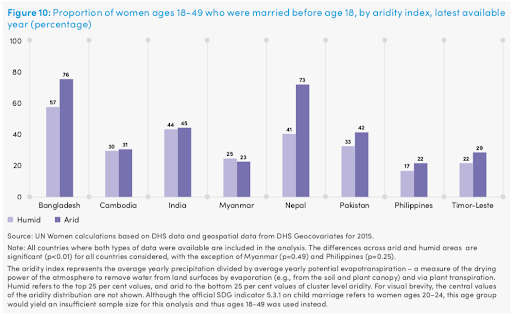

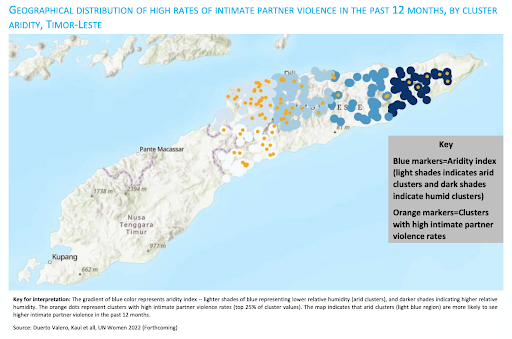

Integrating gender into disaster and climate change statistics in select Asia-Pacific countries reveals that droughts, risk of flood, aridity index, temperature increases, and distance to lakes and oceans are significant factors contributing to the risk of child marriage, adolescent births, and intimate partner violence (IPV).

Empirical analysis indicates a higher prevalence of child marriage in areas that are more arid and where droughts are more frequent, though this finding appears to correlate specifically to countries where child marriage is culturally prevalent (e.g., Bangladesh and Nepal) on top of other factors driving the practice (Figures 1 and 2). According to UN Women, arid regions also experience higher rates of IPV, as is the case in Timor-Leste (Figure 3).

Disasters magnify existing gender inequalities which shape the way men and women experience and respond to them, with women disproportionately bearing the impacts. Yet, the development of disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) policies, strategies, and initiatives often excludes women. Humanitarian action to address these disasters is most effective not only when it meets the immediate needs of the most vulnerable, but also when it protects their rights and builds their resilience for the long-term. With disasters increasing in frequency and severity across the world, the role of technology, specifically information and communications technology (ICT), in strengthening the resilience of individuals and communities has never been more pronounced. Digital spaces have made it possible to access vital information, services, and networks for disaster risk and response – the next step is making these spaces available, accessible, and empowering for women.

Why ICT is Key to Building Disaster Resilience

Information is power, and even more so during disasters. Technologies facilitate access to information and can help people make more informed decisions for a successful disaster management system. However, women often miss out on timely and relevant information due to unequal access to technology, communications, and services; thus, making them even more vulnerable to these natural hazards. According to the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), not only does a woman’s ability to access accurate information on disasters affect her own survival, but it also has a direct impact on her community. Having more resilient women thus means more resilient societies. When women are actively engaged in the design, implementation, and use of disaster risk reduction technologies, DRRM efforts are ultimately more effective because they are made more accessible and inclusive.

Disaster risk management is essentially information-driven, making ICTs crucial lifelines when a disaster strikes. Technologies such as mobile phones, radios, televisions, hotlines, social media and the internet are among the many tools which women can use before, during, and after a disaster. The wide range of ICT tools in DRRM can be aligned to the four phases of disaster risk management:

- Mitigation – This initial phase is aimed at reducing a disaster’s impacts. Some examples of ICT usage can include vulnerability assessments and public education on disasters.

- Preparation – The second phase is about preparing for how to respond to a disaster, which includes emergency planning, training drills, and early warning systems.

- Response – This phase focuses on the efforts to reduce the hazards caused by a disaster. ICT tools at this stage can include crisis mapping, information management, and robotic search and rescue.

- Recovery – Finally, the last phase deals with how to bring the affected community back to its previous state. ICTs here can be useful for funding and relief aid distribution, short-term housing, contact tracing, medical care and other recovery services.

With more and more users of mobile phones globally, governments and humanitarian organizations have utilized their potential as an early warning system. Fundraising, disaster relief efforts, and DRRM awareness raising, and education are also among the other possible benefits of integrating mobile phones in DRRM efforts. Moreover, the near ubiquity of mobile phones has made it easier to derive big data from mobile phone usage that can be especially useful during emergencies. In cases where communication systems and power grids fail, technologies like radio allow people to stay informed of impending disasters and provide real-time updates on events. Broadcast radio can also be used as an early warning and awareness-raising tool while providing localized information with official instructions from authorities. Through satellite radio, on the other hand, responders can quickly send satellite images of an emergency to a disaster command center where high-performance computers can better map the terrain and the situation on the ground.

The internet has also been widely used as a tool to monitor, report, and share information on disasters. It provides users with the ability to access a wide range of news sources online and is also used to coordinate relief and response operations, while providing near real-time alerts to users. Online forums and portals that rely on information exchange for long-term recovery, preparation, and mitigation activities are also available. Lastly, through the internet, the use of social media has redefined DRRM in terms of reach, timeliness, and creativity. Social media allows for on-the-spot citizen reporting by empowering users to control, interact, and connect their mobile devices to disseminate information and coordinate disaster-related operations. Not only is this platform widely used by ordinary citizens, but government officials and emergency response authorities also rely on social media to keep the public up to date on disasters and inform them on how they plan to respond and reach out to affected areas. Given the rapid advances in technology, ICTs can now also provide more sophisticated solutions through space-based technologies like geographic information systems (GIS), remote sensing and satellite communications which make it possible to identify, map, and analyze disaster information with unprecedented detail.

ICTs can instantly link massive networks of people and organizations across huge distances and can facilitate the movement of vital information before, during, and after disasters. The key phases of the DRRM cycle may now leverage this enormous quantity of data and information thanks to advances in ICT. As new and emerging technologies begin to serve as powerful tools toward inclusive and resilient DRRM, ICTs have not only strengthened disaster resilience, but have also boosted the adaptive capacity of its users in the face of disasters. ICTs have been integrated into more and more government strategies as countries recognize the growing urgency of embracing digital connectivity for greater societal resilience. Embracing ICT as the way forward, however, entails expanding ICT connectivity to all stakeholders involved––including (and especially) women.

Bridging the Digital Gender Divide

ICTs offer innumerable solutions for disaster management, but the prevailing digital gender divide limits their impact. Women generally have less access to ICTs than men, and when compounded with lower levels of digital literacy amongst women, it is much more difficult for them to receive timely and critical information, grasp it, and act on it. Equal access to ICTs is necessary to increase disaster resilience, and without women and girls taking part as equal stakeholders, their lives and the wider community are at greater risk during disasters.

According to UNICEF, gender inequality in the real, physical world is mirrored in the digital world. The digital gender gap, underpinned by traditional gender norms, exists in both access to and usage of digital tools, blocking women from taking advantage of the full range of opportunities offered by ICTs. Across the world, men are 12% more likely than women to be online. In terms of content delivery, it is also common for disaster-related information to be delivered through male-dominated channels and is thus perceived to be less gender-sensitive, accessible, and appealing to women and girls. In 2015, for example, women’s visibility in newspaper, television, and radio news was only 24%, which was the same percentage as in 2010, according to the Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP).

Women’s exclusion in the ICT field is most felt in countries that are late to adapt to the digital information era, the same countries which are also more prone to disasters. In the Asia Pacific region, which has experienced more natural disasters than any other parts of the world, only 54% of women use the internet compared to 59% of men. However, the digital gender divide is even more steep in South Asia where women are 36% less likely to be internet users than men. Most countries with a gender gap in internet usage also reflect a significant gender divide in mobile phone ownership. While mobile phone penetration varies across the Asia Pacific, South Asia, for example, has a larger mobile phone ownership gender gap than any other region.

Although there is growing recognition of the potential of ICTs for DRRM initiatives, ICTs risk aggravating existing gender inequalities in disaster settings if women cannot access and use them. Further challenges to bridging the gender digital divide include financial constraints, the construction of ICT infrastructure, and socio-cultural norms and perceptions surrounding ICTs and women’s involvement in the design and implementation of digital and technological tools. In some countries in the Asia Pacific, for instance, women need ICT education to equip them with the skills and confidence to actually use the digital technologies that they already know about. It is also necessary to ensure that the online world is a safe space for women and girls. Thus, increased investment in the holistic design and delivery of ICTs that addresses women’s specific needs, as well as boosting support for women in the field of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) would greatly contribute to closing the digital gender divide and reaping the benefits of emerging technologies and innovation for disaster management.

Women and ICTs: Best Practices in Asia Pacific in 5 Country Case Studies

The increasing frequency of disasters demands newer innovations in ICT and the involvement of more stakeholders, especially women. Despite the existing digital gender divide, disaster-affected countries have innovated several best practices when it comes to strengthening women’s connectivity to ICTs, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. The Asia-Pacific is the most disaster-prone region in the world. Over the past 50 years, 6.9 billion people in the region have been affected by natural disasters and over 2 million people have been killed by storms, floods, and droughts. Around 45% of all the world’s natural disasters take place in this region and many countries have since then devised more robust systems to strengthen their resilience against these calamities. While the region often finds itself in the eye of several storms, homegrown ICT breakthroughs that actively involve and engage women across the region prove how disaster resilience, through women’s increased connectivity, can outpace disaster risk.

In Indonesia, for example, an all-women team developed a data-driven solution to flood mitigation. The project Nusantara Analysis Flood, or Nusaflood, created a system that utilizes interactive spatial visualization to estimate the impact of future flooding in affected populations. According to the team, women can be both developers and users of GIS technology. Nusaflood was designed to be easily operated by anyone regardless of their technological literacy and through this, users can identify certain flood-prone zones and inform their decision-making on choosing where to work or live in Indonesia.

Any DRRM planning or response should also take into account the needs of pregnant women and newborns during disasters and develop appropriate interventions to boost their resilience. When a major earthquake hit Nepal in 2015, victims included pregnant women or those who had just delivered who were left homeless after the quake destroyed houses and health infrastructure. Following this disaster, the Maternal and Neonatal Technologies in Rural Areas (MANTRA) mobile application was developed to improve maternal and newborn health resilience in Nepal before, during, and after disasters. MANTRA is a unique mobile health (mHealth) intervention with game components that tackles geo-hazards, maternal, and child healthcare modules through a user-friendly interface and locally tailored visuals. Users have demonstrated greater knowledge of early warning signs and growing mobile phone ownership and network coverage in rural Nepal show prospects of integrating MANTRA into the national health infrastructure.

In Fiji, women are not only receiving disaster-relevant information, they are also empowered as the first responders. After a devastating cyclone struck the country in 2009, the feminist NGO femLINKpacific launched an innovative information communication system called the Women’s Weather Watch (WWW) to monitor approaching disasters and provide real-time information. What started as a simple bulk SMS messaging across a core group of rural women leaders in Fiji is now an interoperable communication platform linking a network of 350 Fijian women through community media, including radios, SMS alerts, a Viber group, and a Facebook page. The WWW is a two-way system, enabling members to be both receivers and providers of information and connecting them with the relevant authorities and stakeholders. It serves as a platform to document the lived realities of different groups (e.g. elderly, women, children, disabled, sexual minorities) especially in rural communities and advocates for gender-inclusive DRRM efforts and humanitarian responses through the leadership of women in disaster decision-making. Through the WWW platform, there has been stronger visibility of the diverse needs of women within the media and government strategies. In 2018, the WWW expanded its work to a wider regional scale reaching the Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu.

Basic emergency hotlines have also been used by women as key communication channels during disasters. It is best practice to have a single phone number for queries and reports of crisis-related needs that can also handle the intersecting vulnerabilities for women, especially in cases of GBV. In the Philippines, the most typhoon-impacted country in the world, GBV emergency services are sparse and not easily accessible (especially during and after disasters). Thus, the Coalitions for Change, in collaboration with The Asia Foundation in the Philippines, proposed incorporating GBV response capabilities into the national 911 emergency hotline. Calls received through the 911 hotline previously only covered search and rescue assistance, emergencies, disaster services, and police cases. Since 2021, victim-survivors and informants of GBV can now confidentially also use the toll-free hotline, which is easier to reach and available 24/7. Emergency responders were trained to handle GBV cases by providing psychological first aid and “survivor-centered care” and making immediate referrals to the relevant agencies. By identifying GBV as a case for immediate response and understanding how its prevalence is linked to disasters, an existing policy framework was transformed into a more reliable safety net that women can turn to if they find themselves in these situations.

Disasters also impact food security by disrupting agricultural production. In Cambodia, where 53% of women are employed in the agricultural sector, these women increasingly need advice to understand and adapt to changes triggered by disasters and climate variability. However, agents who provide agricultural extension services offering technical advice and tools to support their production often only approach male farmers, because of preconceived notions women do not farm and that the knowledge imparted to males will be freely shared within the household. It was discovered that through technologically-driven approaches (e.g. radios, mobile phones, and videos) delivered by female agents, these extension services can effectively reach women. Donors and NGOs are more likely to deliver information to female farmers in Cambodia through unwritten material designed and delivered by other women, taking into account women’s needs, priorities, and constraints.

Despite being extremely susceptible to disasters, the Asia Pacific region as a whole has taken great strides to strengthen its resilience. Through the creative and innovative use of ICT that involves and engages women, the most affected communities are more prepared for the next disaster and in a stronger position to build back better afterwards.

Conclusion

As the world continues to experience increased disasters, and with the trend only expected to accelerate in the future, it becomes all the more urgent to understand the link between gender and disasters. Disasters unfold in societies shaped by structural inequalities, and their impacts often reflect and reinforce pre-existing gender inequalities. Men and women experience disasters in different ways, relying on information they receive before, during, and after such disasters. Women and girls are more vulnerable to disasters than men and boys because of the unequal (or the lack of) access to information and resources that may have enabled them to respond better. Thus, there is a strong imperative to make women equal partners in the conversation, especially when it concerns not only their individual safety, but also that of her family and the community at large.

With women’s unique experiences and skills, they can be powerful agents of disaster resilience. Given the right tools and information, together with an enabling environment that will allow women and girls to best exercise their potential, they can be active leaders and responders in disaster settings. ICTs have proven to be critical to all stages of disaster risk management. Investing in greater connectivity for women can help improve how the humanitarian community addresses the gender-differentiated impacts of disasters and minimize the impact of such events on the most vulnerable, while also working towards building more sustainable and resilient communities. This does not necessarily mean investing in the most sophisticated and expensive technological tools, but rather making women’s inclusion in the use and access of ICTs intentional and meaningful. Women are capable of developing, implementing, and leading transformative digital solutions to disaster resilience. Moving forward, technological innovations targeted toward, tailored to, and led by women can help build a more connected, informed, and dignified future for everyone. Though disaster resilient communities do not form overnight, increasing women’s connectivity to ICTs helps them rise better and stronger once the clouds have cleared.

About the author: Stacey Bellido is a Research and Content Intern with Data-Pop Alliance’s Resilient Livelihoods and Ecosystems and Data Feminism Programs. She is from the Philippines and currently resides in France.

References

- Asian Development Bank. (2020). Enhancing Women-Focused Investments in Climate and Disaster Resilience. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/605606/women-focused-climate-disaster-resilience.pdf.

- Chi, H.; Tolosa, K. (2022). Call for Help: Gender-Based Violence and 911 in the Philippines. The Asia Foundation. https://reliefweb.int/report/philippines/call-help-gender-based-violence-and-911-philippines.

- Enarson, E. (2018). Men, masculinities and disaster: An action research agenda. In Men, Masculinities, and Disasters. DOI:10.4324/9781315678122-19.

- Enarson, E.; Fordham, M. (2001). From women’s needs to women’s rights in disasters. Environmental Hazards. Environmental Hazards, Human and Policy Dimensions: 3(3): 133–136. DOI:10.3763/ehaz.2001.0314.

- FemLINKpacific. (2020). Women’s Weather Watch Amplifies Women’s Roles as First Responders. ********https://www.femlinkpacific.org.fj/newsupdates/womens-weather-watch-amplifies-womens-role-as-first-responders.

- Gender-based Violence Areas of Responsibility Helpdesk. (2021). Climate Change and Gender-Based Violence: What Are the Links? GBV AoR Global Protection Cluster. https://gbvaor.net/sites/default/files/2021-03/gbv-aor-helpdesk-climate-change-gbv-19032021.pdf.

- Global Media Monitoring Project. (2015). Who Makes the News? https://www.media-diversity.org/additional-files/Who_Makes_the_News_-_Global_Media_Monitoring_Project.pdf.

- Global System for Mobile Communications. (2019). The Mobile Gender Gap: Asia. https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-in-Asia.pdf.

- International Telecommunication Union. (2020). Women, ICT and emergency telecommunications: opportunities and constraints. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Emergency-Telecommunications/Documents/events/2020/Women-ICT-ET/Full-report.pdf.

- International Telecommunication Union. (2020). The Gender Digital Divide. https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2021/11/15/the-gender-digital-divide/.

- International Telecommunication Union. (2022). Big Data for development: preventing the spread of epidemics. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Emergency-Telecommunications/Pages/BigData/default.aspx.

- Mueller, S.; Soriano, D.; Boscor, A. et al. (2019). MANTRA: a serious game improving knowledge of maternal and neonatal health and geohazards in Nepal. The European Journal of Public Health: 8. DOI:10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.329

- Okai, A. (2022). Women are hit hardest in disasters, so why are responses too often gender-blind? UNDP. **https://www.undp.org/blog/women-are-hit-hardest-disasters-so-why-are-responses-too-often-gender-blind.

- Pudmenzky, C.; Lisk, I.; Vitols, L. et al. (2022). Gender equality in the context of multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk reduction. World Meteorological Organization. https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/bulletin/gender-equality-context-of-multi-hazard-early-warning-systems-and-disaster-risk.

- The Asia Foundation. (2021). 911 National Emergency Hotline to Assist VAWC and GBV Survivors in The Philippines. https://asiafoundation.org/2021/12/08/911-national-emergency-hotline-to-assist-vawc-and-gbv-survivors-in-the-philippines/.

- UNDP. (2021). Alluvione: Girl power to combat floods in Indonesia. https://www.undp.org/asia-pacific/news/alluvione-girl-power-combat-floods-indonesia.

- UNESCAP. (2016). ICT in Disaster Risk Management Initiatives in Asia and the Pacific. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/ICT4DRR Iniatives in Asia-Pacific_0.pdf.

- UNESCAP. (2022). E-Resilience in Asia and The Pacific. https://drrgateway.net/e-resilience/about.

- UNFPA. (2018). Delivering Supplies When Crisis Strikes: A Regional Overview of Asia and The Pacific. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/18-291-DeliveringSuppliesCrisis-Asia-finalweb.pdf.

- UNICEF East Asia and Pacific. (2021). What we know about the gender digital divide for girls: A literature review. https://www.unicef.org/eap/reports/innovation-and-technology-gender-equality-0

- UN Women. (2022a). Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/humanitarian-action/disaster-risk-reduction.

- UN Women. (2022b). Women and the Environment: An Asia-Pacific Snapshot. https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/Publications/APRO_Women-environment-snapshot.pdf.

- UN Women. (2022c). Integrating Gender into Disaster and Climate Change Statistics: The Asia-Pacific Experience. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/event-documents/UNWomen_UNSC2022_Side_Event_DRS_14Feb2022.pdf

- Women’s UN Report Network. (2018). femLINKpacific Women’s Weather Watch of Fiji Goes Regional. https://wunrn.com/2018/02/femlinkpacific-womens-weather-watch-of-fiji-goes-regional/.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)