Welcome to the fourth edition of Data-Pop Alliance’s series, “Employee Spotlight,” where we shine a light on the talented individuals who make up Data-Pop Alliance. Our team members are what makes DPA thrive, and through this series, we aim to highlight their diverse backgrounds and inspiring stories. Today, we’re excited to feature Adjani Gama Dessavre, (Data Scientist & Front-End Developer) and Enrique Bonilla (Data Scientist & Engineer). Based in Mexico City, this dynamic couple collaborates on our Data Science Team, contributing to complex research and developing innovative dashboards that enhance accessibility. Read on to discover their journey, what they love about their roles, and how they give back to the community.

*This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

DPA: Could you share 1-2 books (fiction or nonfiction) that shaped you?

Adjani Gama Dessavre (AGD): This is a really tough question because choosing just one book (or one of anything) is quite challenging. However, I would say “The Neverending Story” by Michael Ende. It was one of the first books that made me fall in love with fantasy. Both fantasy and science fiction have shaped the way I think, and I really enjoy these genres. The flow of this book is amazing. As a child, I always kept my copy next to my bed because it was my favorite book.

Enrique Bonilla (EB): For me, it’s actually not a book, but rather a graphic novel. However, I believe it has the same depth and quality as a traditional book, even though graphic novels are often thought of as just for kids. The graphic novel I chose is “Watchmen” by Alan Moore. It was the first graphic novel that truly engaged me and introduced me to the genre. The storytelling is outstanding, and it offers insightful critiques of American society and society as a whole. I believe “Watchmen” has definitely left a mark on me.

Tell us about your academic and professional background before DPA. Feel free to mention other key achievements and experiences that were particularly relevant to you.

AGD: Before joining DPA, I had a strong academic background. I hold a bachelor’s degree in applied mathematics from Mexico and a master’s degree in “interdisciplinary mathematics” from the UK, which is essentially applied mathematics. This education led me to work with an organization focused on Neglected Tropical Diseases, studying diseases that have largely been eradicated in the Global North but still affect regions like Africa and Mexico, including dengue and malaria. I really enjoyed the research aspect of that work.

I’ve always integrated a lot of computer science into my profession, which is not common among mathematicians. This skill set enabled me to conduct simulations, which were particularly useful for our research.

After my studies, I returned to Mexico because I missed it and also found it challenging to obtain visas in the UK. I started teaching at the bachelor’s level and discovered that I loved it. However, I had to stop teaching when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, as it became overwhelming and time-consuming. Following that, I began working in the chemistry department at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico), where I focused on data analysis.

Eventually, my dream job at DPA became available, which combines all of my academic and professional experiences. I’m also a writer—I recently completed my first novel—and I’ve studied animation, which allows me to explore my more artistic side.

EB: My professional journey began at ITAM (Mexico’s Autonomous Institute of Technology), which is actually where Adjani and I met. I studied applied mathematics there. After graduating, I landed my first job at Las Quince Letras, where I worked in market research and data science.

I then went to the University of Edinburgh to pursue a master’s degree. Upon returning to Mexico, I worked as a data and research scientist at Datank and later at Luxelare, where I served as a data scientist and engineer. While at Luxelare, I focused on analyzing satellite images for data science projects.

Eventually, I started my current role at DPA, and I want to express my gratitude to everyone I met throughout these experiences. They have been amazing, and I wouldn’t be here at DPA without their support.

DPA has done research on the lack of women’s participation in STEM and barriers they face, specifically in Mexico. Do you feel that the situation has improved over the course of your education or career? Have you noticed any differences in gender parity since you began? We’d love to hear your personal perspectives on this.

AGD: This is a really complicated question because the answer is both yes and no. Yes, because there’s been much more visibility on these issues, and it’s easier to point out what’s happening and take action. But no, because I still see these things happening, and they’re often covered up.

For example, at an institution where I worked, and one that we’ve studied extensively, many issues still occur, and it’s clear that the system isn’t doing enough to make them disappear. Students are often left to fight for change, which shouldn’t be the case. It’s great that students are involved, but the system should also take responsibility. From firsthand experience, I’ve seen things being covered up.

I actually testified in a case where something was happening, and I can say it’s hard for people to speak up because they’re afraid of losing their jobs. I understand that, of course. On one hand, it’s good that these situations are becoming more visible, but on the other, it’s frustrating to see that basic issues still persist.

For example, when Enrique and I were considering studying for our PhDs, we had both already completed our master’s degrees and were asking for recommendation letters from the same set of people. Everything went smoothly, but there was one difference: I got asked a question that Enrique never received. They asked me, “Aren’t you going to get married or have children?” I was shocked—why was that only directed at me? Marriage and children would involve both of us, so why is that question only for me?

These kinds of situations keep happening, and that’s why my answer is complicated. Yes, there’s progress, but no, because these issues are still present and being overlooked.

They asked me, "Aren’t you going to get married or have children?" I was shocked—why was that only directed at me? Marriage and children would involve both of us, so why is that question only for me?

Adjani Gama Dessavre

EB: From my perspective, I should start by saying that I’m a progressive. Mathematically, I like to describe the situation with gender rights and other issues as a linear function with a positive slope, plus a cosine function. It’s like a positive line, always going upwards, but with ups and downs, like the waves in a cosine curve.

It’s hard to explain without a visual, but the idea is that we’re always moving toward progress, even if there are occasional setbacks. These setbacks often depend on political situations or conservative tendencies, but overall, I believe that progress keeps moving forward. Thanks to the efforts of many people, especially women, who work hard to address these issues, we continue to make strides, at least in some parts of the world.

For example, in Mexico, over the past 10 years, there has been significant progress in abortion rights and increased awareness of women’s rights. I see it in my nieces, who have a much better understanding of gender issues than I did at their age. That makes me feel really hopeful, even though the fight can sometimes seem difficult.

What inspired you to want to join DPA’s team?

AGD: Oh my god, Enrique! I’ve always wanted to work in this kind of area, but when I was at UNAM, I was doing more data science work—focused on improving student life, or things like that—but it wasn’t quite what DPA does. At that time, while still in Mexico, I had almost given up on working in the development sector. I didn’t think it was possible for a mathematician like me to get into that field anymore. I was losing hope, especially because, as a woman, I received fewer opportunities. That’s the topic again, right?

Then, Enrique would tell me about his new job, and I’d think, “Wait, you do what? That’s amazing!” Later, I took a gender course—I think it was called Gender Data 201, though I don’t remember the exact name. Anna (Spinardi, DPA Data Feminism Director) led my group, and Natalie (Grover, DPA Managing Director) was also one of my teachers. I was blown away. I thought, “These people are incredible—I need to work with them!”

So, I told Enrique, “If anything ever opens up, you have to let me know because this is the place I need to be.” What really inspired me was seeing all of you—how passionate you were and how well you executed your work. UNAM is great, but it’s very bureaucratic, and things move slowly. Often, you don’t see much happening. But after just a couple of classes with you all, it was clear that you knew exactly how to start a project, how to break things down, and what questions to ask. I just really, really wanted to work at DPA.

EB: From my side, I have to mention two people I’m particularly grateful for: Liliana Millan and Jesus Ramos. They were my previous bosses at Datank , and they’ve always been dedicated to using data for social good. They consistently pushed forward what they believed was best in terms of data-driven solutions.

I remember one time when I talked to Jesus—well, I know him as Chucho—and he told me, “Working for social good with data is the best thing you can do in data science. Once you’re in, you won’t want to go back.” That really stuck with me.

Actually, I was working for him in my previous job before coming to DPA, and I saw a position related to data and social good on LinkedIn. I thought it would be a great opportunity, so I asked him about it. Even though I was still working for him, he wrote me a recommendation letter. Interestingly Zinnya (del Villar) our Data Team Lead here at DPA knows him, and they vouched for me too, saying, “I know this guy—he’s really good.” Everything just connected from there.

I’m really, really thankful to both Liliana and Jesus. They inspired me so much, and without Jesus’s help, I don’t think I’d be here today. So, thanks, guys!

Can you give us an overview of the types of work the Data Science Team does at DPA, and how this differs from those working on our projects in more qualitative ways?

AGD: DPA is amazing because you get to work on so many different kinds of tasks, making it hard to describe a “typical” day. But let me walk you through one. We start with a morning meeting with the whole team, which has helped us grow really close. It’s not just about sharing what we’re working on and our to-do lists—it’s also early for us and late for others, so we often end up chatting about other things, which is really nice.

As for the work itself, it varies a lot. Some days feel like being in a cave—you’re in front of the computer, super focused, programming nonstop. Right now, I’m doing front-end development, Enrique is working on back-end, and everyone is heavily involved in programming. Those are the days when you’re so concentrated that by 4 p.m., you might have a headache from staring at the screen for so long.

Then there are other days where the tasks are more varied. You might be reviewing data, or using creativity to solve problems. People assume that because we’re on the data science team, it’s all about logic and structure. But in reality, we need a lot of creativity, whether it’s solving algorithms or figuring out what to do with messy, incomplete data. I do a lot of data visualization, and I love that part of my job because I get to combine storytelling with making things visually appealing. It’s great, especially since I have a background in the arts.

How does our work differ from other teams? It’s hard to pinpoint one thing because each team’s job is so different. But I think one major difference is how we work. We’re not very linear—we tend to be more horizontally structured, meaning we share tasks and ideas across the team. DPA, in general, is very horizontal, but our team is especially flexible. It’s rarely about finishing task A before moving to task B—it’s more like managing a bunch of tasks at once and organizing them as best as we can.

We also have a more technical side, which can lead to what I call “cave moments”—when you’re alone, programming, and fully immersed. One unique challenge we face is losing time over technical glitches, like when Linux and Windows won’t cooperate or when you spend a whole day trying to fix a missing slash or comma in your code. Those days can be frustrating, but it’s part of the job.

EB: Building on what Adjani said, I’ve often been asked about the difference between a data analyst and a data scientist, especially since my first job. A data analyst typically focuses on analyzing data—creating plots, finding correlations, and interpreting the data. Their job is mainly about analysis.

However, a data scientist has to know a little bit of everything. You need to understand how to work with cloud platforms, virtual machines, and deal with large datasets—sometimes terabytes of data—with limited resources. This means you have to know how to manage those resources without crashing your system. You also need knowledge in a wide range of areas, from deep learning to statistics, from plotting data to data ethics, privacy, and governance.

A data scientist has to be familiar with data engineering, software development, and building platforms to efficiently share data. You also need to know about every step in the data processing pipeline—data cleaning, optimization algorithms for training models, and more. So, the key difference is that a data scientist’s work is much broader and more technical.

But, as Adjani mentioned, it’s not just the technical side. I think what’s particularly fascinating about being a data scientist at DPA is the non-technical work we get to do. This includes research and figuring out how to communicate data insights to policy experts who may not be familiar with all the technical details. Building that bridge between data science and other fields, making complex information understandable to everyone—that’s a huge part of the role, and I find it really rewarding.

However, a data scientist has to know a little bit of everything. You need to understand how to work with cloud platforms, virtual machines, and deal with large datasets—sometimes terabytes of data—with limited resources. This means you have to know how to manage those resources without crashing your system. You also need knowledge in a wide range of areas, from deep learning to statistics, from plotting data to data ethics, privacy, and governance.

Enrique Bonilla

AGD: We’ve been involved in many projects, each with its unique aspects that we love. However, there are two specific ones that stand out for me.

The first is the Fòs Feminista project, which was just amazing. The team created such a great environment, making it easy to communicate with the client. We came up with some really creative solutions that made the final product beautiful. My role was to build the dashboard for Fòs Feminista, a digital health compendium. I’m particularly proud of this dashboard because it’s not only visually appealing but also highly functional. It’s translated into different languages and presents information in a way that makes sense.

I must emphasize that my success in creating this dashboard wasn’t solely due to my skills. It was a team effort, with everyone contributing—like the people handling translations and the data analyst who cleaned the data. Without their hard work, it would have been much more challenging.

The second project I love is the one we’re currently developing called Abogadas-México. What excites me most about this project is that we’re doing something completely different. I’m using a new programming language, React, which means I’m building everything from scratch. This return to programming has been invigorating. We also have excellent communication with the client, which makes it easy to suggest changes that align with their goals.

So, I’d say those two projects are my favorites so far!

EB: I actually have two favorite projects: one old and one new. The first one is the UNESCO report on misinformation and disinformation. I’m not sure if I’m stating the exact title correctly, but I believe it’s from the UN or one of its sub-institutions. This report is published every four years, and I had the opportunity to work on it about two years ago. It was an amazing experience; I learned a lot technically.

While there weren’t many challenges in terms of modeling—most of the analysis involved creating graphs and simple correlations—the real challenge lay in two areas. First, how to communicate the interesting findings we uncovered. Even with basic plots and correlations, we identified significant trends. We regularly compared the state of misinformation now with that of four years ago, and discovering increases and decreases in certain areas was truly fascinating.

The second challenge was gathering information from over 100 sources. We had to clean the data and make sense of it all. Sometimes the sources contradicted each other, so it was essential to create a coherent narrative, identify patterns, and understand why some data varied. I learned a great deal about misinformation globally, and I also picked up many country names since I’m not very good at geography, which was a nice bonus!

The second project I’m excited about right now is the OPAL platform. I’m really happy to be working on this one because it’s very technical. I love the idea of making a tangible impact on the world. Often, in projects like the UN report, you end up doing simple tasks like graphs and correlations, but with OPAL, we’re focusing on development and going live.

DPA: You are both active in community projects outside of work, can you tell more about the data science work you do apart from DPA (ConCiencia, ect.)?

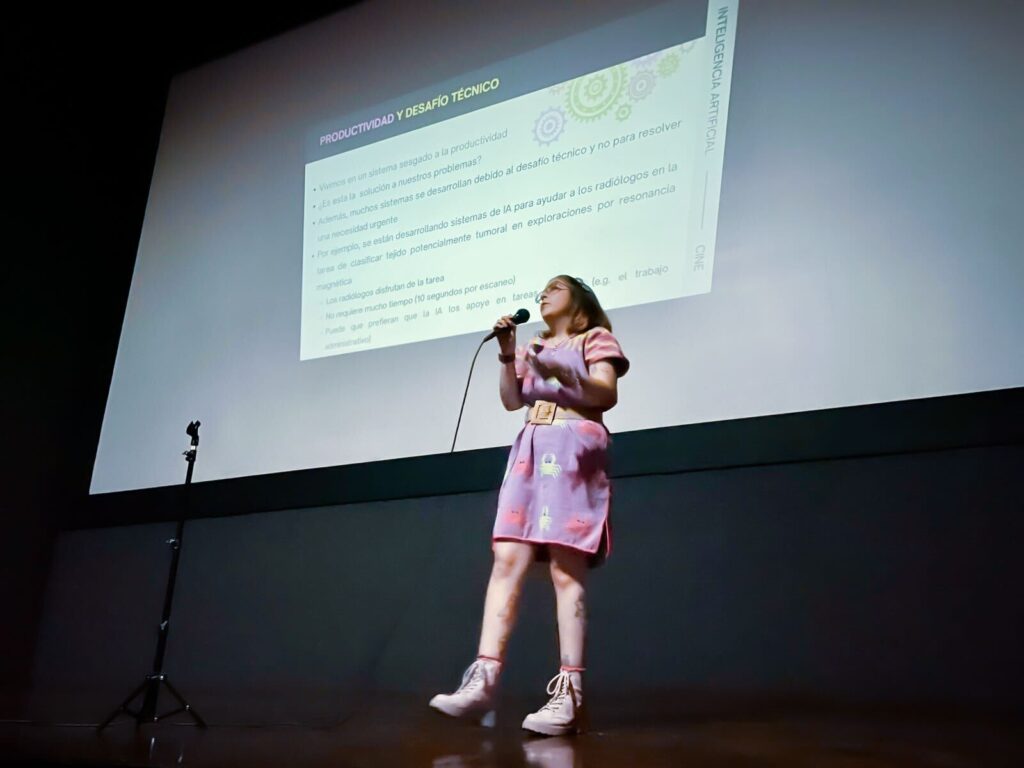

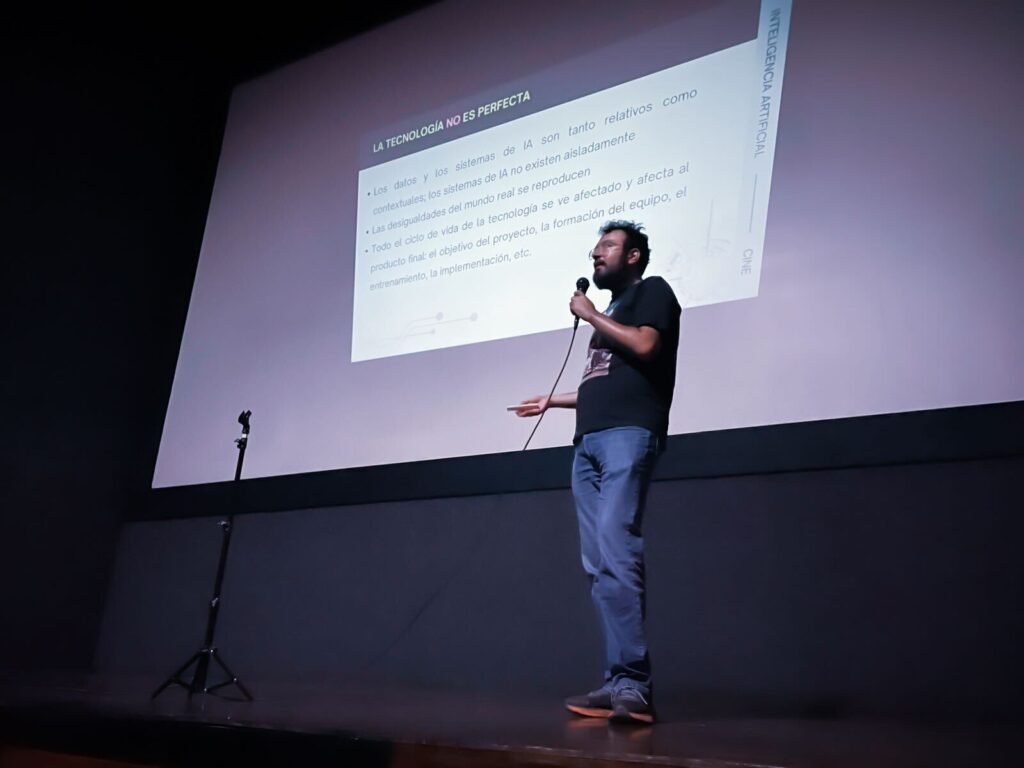

AGD: I believe that many aspects of our lives connect in ways we might not immediately realize, and that’s how some of our projects came to be. One of these is ConCiencia Social, which was a series of conferences we held in Orizaba and Mérida. The inspiration for this came from a combination of seemingly unrelated things.

First, our love for cinema. We noticed that many of the ethical issues surrounding data science and artificial intelligence had already been explored in films. That made us think, “Why not show people how these two areas are connected?” Then, during the COVID-19 quarantine, Enrique, who’s a DJ, would stream music, and I became the audio and streaming engineer, setting everything up so our friends could stay connected. It was this experience of creating something for others that got Enrique thinking about *ConCiencia Social*. He realized that all the big talks and science-related events were happening in Mexico City or Monterrey, but many other cities weren’t getting these opportunities. He wanted to bring these kinds of events to his hometown, Orizaba, and the idea grew from there.

We started reaching out to people and explaining that we wanted to create a series of accessible conferences for everyone. One thing I noticed when I was just starting my career, and later when I worked with students at the chemistry faculty, is that many people have no idea what they’re going to do with their degree. For example, as an applied mathematician, I didn’t like finance, which is what most people were doing. So I wondered, “What am I going to do?” It’s easy to feel lost, but the truth is that there are so many possibilities out there. You just need exposure to different perspectives and fields.

That’s what we wanted ConCiencia Social to provide—an opportunity for people to learn about different paths. Our talk, for instance, was about cinema and artificial intelligence. We explored how many issues in AI today, such as ethics, have already been addressed in films. It’s about bringing together different disciplines, and these spaces allowed people from various fields to meet. I remember a doctor connecting with an engineer working in neuroscience, and the doctor said, “Your research is so relevant to my work in psychiatry!” It was amazing to see those kinds of interactions.

What was even more rewarding was seeing young people—students at the start of their careers—get excited and ask, “How do I do this? How does this exist?” Creating a space for that curiosity and connection was truly inspiring.

EB: I completely agree with what Adjani said about the importance of community. For us, it’s not just about working together professionally, but also personally. We like to collaborate on every project we can, whenever possible. Like Adjani mentioned, I DJ and she does audio engineering. When we made a short film, I was the director, and she handled the audio and most of the post-production. We love sharing this sense of community with everyone we can, starting with our friends.

We often involve our friends in our projects. For example, with the short film we’re currently developing, we’ve asked our friends for help. Even at our wedding, we put on musical numbers that our friends participated in—we had them rehearse the steps and be part of the performance. It was a bit unconventional, but a lot of fun!

This sense of community extends beyond our personal projects and into initiatives like *ConCiencia Social*. As Adjani said, we try to involve scientists and experts from all fields, without discriminating based on their level of education. Whether someone has a PhD, a bachelor’s degree, or no degree at all, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that they are doing meaningful work. We believe in sharing knowledge and creating opportunities for everyone, not just academics.

We aim to make these talks and discussions accessible to people from all walks of life. Whether you’re a farmer, a stay-at-home parent, a student, or a 70-year-old retiree, you should be able to join these spaces and learn something valuable. Everyone can contribute and apply what they learn to their work, and we can learn from them as well.

We also try to bring this sense of community to places that have been historically overlooked or discriminated against, places that don’t have the same resources as big cities like Mexico City. Everything we do together, both Adjani and I, is rooted in this shared belief in community, and we do our best to spread that sense of belonging to everyone we work with.

To learn more about DPA’s team, visit this page.

![M002 - Feature Blog Post [WEB]](https://datapopalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/M002-Feature-Blog-Post-WEB.png)